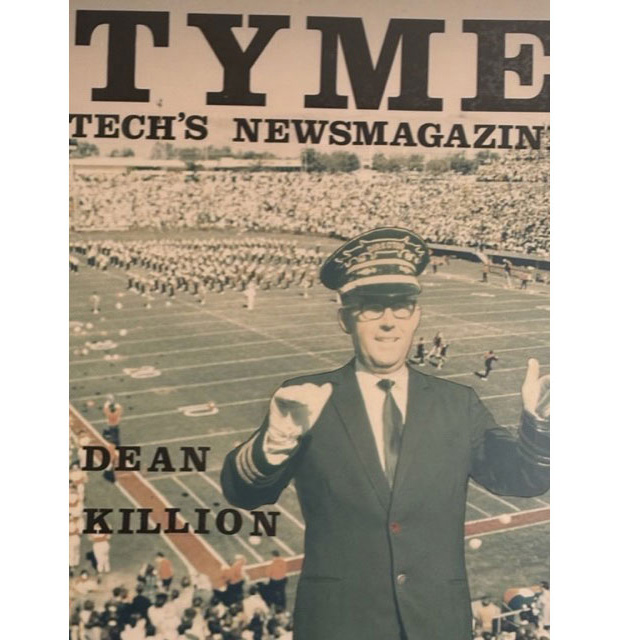

Dean Killion directed the Goin’ Band from Raiderland for 22 years. Now, his great-grandchild will march in the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade.

Hundreds of pairs of feet move back and forth across the pavement. Quick turns are accompanied by quick breaths to keep air moving through instruments.

Texas Tech University’s Goin’ Band from Raiderland is preparing for the Macy’s Day Thanksgiving Day Parade.

The temperature in Lubbock currently mimics that of the cold awaiting the students in New York City. Numb fingers struggle to remain nimble as students practice through a cold snap, unusual this time of year.

One of those students is Andrew Meyer. Andrew is in his first year at Texas Tech. He is a trumpet player and music major. To anyone who has been around the Goin’ Band for some time, there is something familiar about Andrew.

It’s in his eyes. In his obsessive practice regimen. It’s even in his instrument of choice.

Andrew is the great-grandson of Dean Killion who was the director of the Goin’ Band from 1959 through 1981. And Thanksgiving Day, Andrew will march the iconic route through New York City playing music his great-grandfather helped compose.

Prodigy

Marlin “Dean” Killion was born in 1926 in the small town of Fairfield, Nebraska.

The town had only a few hundred people, so the high school football team and marching band were the main sources of entertainment. Killion learned the drums as a very young child, taught by the local high school band director who took an interest in him.

The director’s hunch was correct; Killion had something special.

At merely 4 years old, Killion accompanied the band to Tulsa, Oklahoma, where it performed under the direction of John Philip Sousa.

By seventh grade, Killion needed a new instrument to master. He turned to the trumpet.

He decided he would be a band director, simple as that, his family says. But if there was any doubt, Killion put it to rest when he won the statewide solo competition his senior year of high school.

“There was never a Plan B for my father,” said Barbie Newton, Dean’s oldest child. “He was an incredibly hard worker. I don’t know anyone who rivaled his work ethic.”

After two years of service in the U.S. Navy, Killion attended college at the University of Nebraska, earning his bachelor’s and master’s in music. It was there that he met and married his wife, Pat.

Pat also was a music student; she was a pianist and a vocalist. Together the couple’s lives revolved around music. Not long after having their first two children, Barbie and James, Killion got an offer to become the band director for Fresno State in California. The family loaded up their things and moved out west – the musical instruments taking priority when loaded.

There, they had their third child, Jerry.

The family was happy in California, but when the opportunity to direct a band in Texas came around, Killion found it impossible to say no.

“Marching bands in Texas were something special,” Barbie said. “Texas Tech made my dad an offer he could not refuse.”

Oklahoma also made Killion an offer, to which he just said, “The family is going to Texas.”

Lubbock

The family moved to West Texas, sight unseen. On the day they drove into town, a large dust storm was forming. They couldn’t see the university or even traffic signs through the airborne red dirt.

It was 1959, so most cars did not have air conditioning.

“My dad ended up promising my mother a new car before we even got to the house,” Jerry laughed, remembering sliding out of the backseat covered in dust.

While the first day wasn’t what they bargained for, the family took to Lubbock as quickly as the dust had taken to their belongings. As they cleaned things off and settled in, they were met by the friendliest folks they’d ever met, they said.

“People in Nebraska were nowhere near as gregarious as the people in Lubbock,” Barbie recalled.

The children grew up attending Maedgen Elementary, Evans Junior High and Monterey High School. They attended almost every event the Goin’ Band marched at and even sat with the Saddle Tramps at games.

“Dad was the one who started the tradition of the band’s pregame show followed by the march over to the stadium,” Barbie said. “We’d get there to watch the show and then walk beside the band and go down the tunnel with them to the field.”

This was a normal weekend for the kids.

It wasn’t until they got older that they realized how special that was.

Their access was a thing of envy from their classmates. But life in the Killion family wasn’t just fun and games. Each sibling played an instrument, and their father instilled discipline and dedication in each of them.

“Daddy could be a lot of fun, but like I said, he also was a hard worker and he expected us to be, too,” Barbie said.

Barbie played the flute and twirled, while James and Jerry both played the trumpet.

Killion wanted Jerry to play trombone, but with his father and older brother both being trumpet players, Jerry was convinced it was a rite of passage. And it was a good thing he saw it that way because he went on to become an excellent trumpet player.

While anyone can practice an instrument and make progress, there is something to be said about the anatomy of the musician and the instrument they play.

“I inherited my father’s lips,” Jerry laughed. “It sounds odd, but we both have a mouth that’s perfect for trumpet.”

All three siblings attended Texas Tech and marched in the Goin’ Band. Their father became their band director, but that didn’t bother them. They’d felt like honorary members of the band for so long that when they finally put on the uniform, it felt entirely natural.

The Killion kids received no special treatment. Their father excused himself from their auditions to avoid any accusations of favoritism. Barbie finds that humorous, stating her father would probably be tougher on them than anyone else.

Barbie recalls her father staying up sometimes until two o’clock in the morning, drafting out performances and placing tiny pins precisely where students would stand.

Barbie, James and Jerry were now part of the choreography – not just onlookers at their father’s drafting table.

Marching for their father gave them insights into his personality, deeper than what they saw at home.

On a trip to Austin in 1964, the band stopped in a small town for lunch.

There was only one Black musician in the band at the time. His name was James, and he was on the drum line. While approaching the counter to order with his friends, the restaurant owner informed James he would have to eat in the kitchen.

Not wanting trouble, James silently agreed and ate in the back with the cooks, but not without a few of his friends from the drumline joining him.

A few days later, on the way back to Lubbock, Killion figured they would stop at the same restaurant again – having no idea what had occurred.

When he announced where they’d be having lunch, one of the students told him what had happened to James. Killion didn’t have the bus change course. They drove on to the restaurant.

Killion took James and walked to the counter with his hand on the student’s shoulder – the whole band forming a long line behind them.

“We’d like to order,” Killion told the owner.

The owner’s eyes flickered to James, and back to Killion.

“Strict rule, colored folks have to eat in the kitchen,” he said.

“Well, that’s too bad, because the band is real hungry,” Killion said, patting James on the shoulder and nodding to the hundreds of students behind him. “And if they can’t eat together, then I guess we’ll take our business elsewhere.”

Killion signaled to the students to head back to the bus.

The owner of the restaurant hesitated for a moment, sighed and relented.

“Fine, everyone can sit together.”

That moment was one of many that took the group from just a marching band to the community it is today.

“That’s just who dad was,” Jerry said. “He had a strong sense of fairness and always tried to do the right thing.”

The Next Generation

During their time in the Goin’ Band, all three Killion siblings met their spouses.

Barbie met her husband, Jimmy.

James met his wife, Sherri.

Jerry met his wife, Kristi.

James earned his undergraduate degree in music and went to Texas Tech’s School of Law. He and Kristi have four children.

Jerry earned an undergraduate degree in music and a master’s degree in conducting and became a high school band director, taking after his father. Jerry and Kristi have two children.

Barbie started as a music major but had a love for children and transferred to education, keeping a minor in music. She became a teacher. Barbie and Jimmy had three children: Julie, Jay and Jeff.

Barbie’s husband Jimmy played trombone in college and later became a doctor. With one parent in medicine and the other in education, they still wanted their children involved in music; not only to carry on the family tradition, but because they truly believed it was something special.

Julie played the flute.

Jay played the trumpet.

Then came Jeff who could feel rhythms.

Jeff was born with Cytomegalovirus (CMV) which resulted in deafness. Jeff faced a great many challenges when he was born and remained in the hospital for a month. When Barbie and Jimmy finally brought him home, they knew life would be different for Jeff, especially in a family that was so musical.

“It was very ironic we had a family member who could not hear,” Barbie said. “But Jeff learned to sing in the church choir and even played bells, striking them when the director pointed.”

Barbie always felt there was something of her father in Jeff. She described them both as pistols – knowing what they wanted and stopping at nothing to achieve it.

His mother recalls that when Jeff didn’t want to continue a conversation, he would just close his eyes. Sometimes a smile would accompany the closed eyelids, knowing he successfully struck a nerve.

Jeff had a determination that made life rich. His friends learned to sign, and Jeff never let his disability hold him back.

As Jeff neared the end of elementary school, complications from the virus resurfaced, leading to liver failure.

“Sadly, Jeff died at 10 years old,” Barbie said, a tenderness in her voice all these years later.

Jeff demonstrated there was something special about being a Killion – nothing could stop their love of music. Even if it was felt and not heard.

Passing the Baton

Other hardships loomed over the family.

Around the same time, Killion was diagnosed with a brain tumor. While benign, its size had become problematic. It pushed against other parts of the brain, causing problems with his balance and clarity of mind.

“By the time MRIs were available, dad’s tumor was the size of a golf ball,” Jerry said.

Killion had suffered from splitting headaches since his mid-20s, but without imaging, doctors had no insight as to why. Despite the occasional bouts of dizziness and nausea, he was dedicated to the band and to his students.

Until it became too much.

By 1978, Killion was getting sick almost every day. That’s when doctors finally found the tumor. They scheduled surgery to remove it. The operation was not as safe nor as advanced as it is today; Killion was left with post-operative complications and retired in 1981.

“That was tough on dad,” Jerry said. “He was an active, quick-witted guy and his health slowed him down.”

While Killion had bad days, he also had good ones.

One thing he made time for was giving music lessons to his grandkids.

What was supposed to be an hour-long lesson often spilled into three hours. But the kids enjoyed the time with their grandfather.

“He was a fantastic teacher,” Julie recalled. “He was very disciplined and didn’t mess around, but if you put in the effort, it was really rewarding to work with him.”

And the head-start helped Julie achieve her goal: playing in the Goin’ Band.

She started college in 1996 and marched under the direction of Keith Bearden, Killion’s successor.

There was never a doubt in Julie’s mind where she would attend college. There is a joke in the family that you can go to any state school you want, as long as it’s Texas Tech.

“If I really wanted to go somewhere else, my family would have supported that, but I wanted to be a Red Raider,” Julie said proudly.

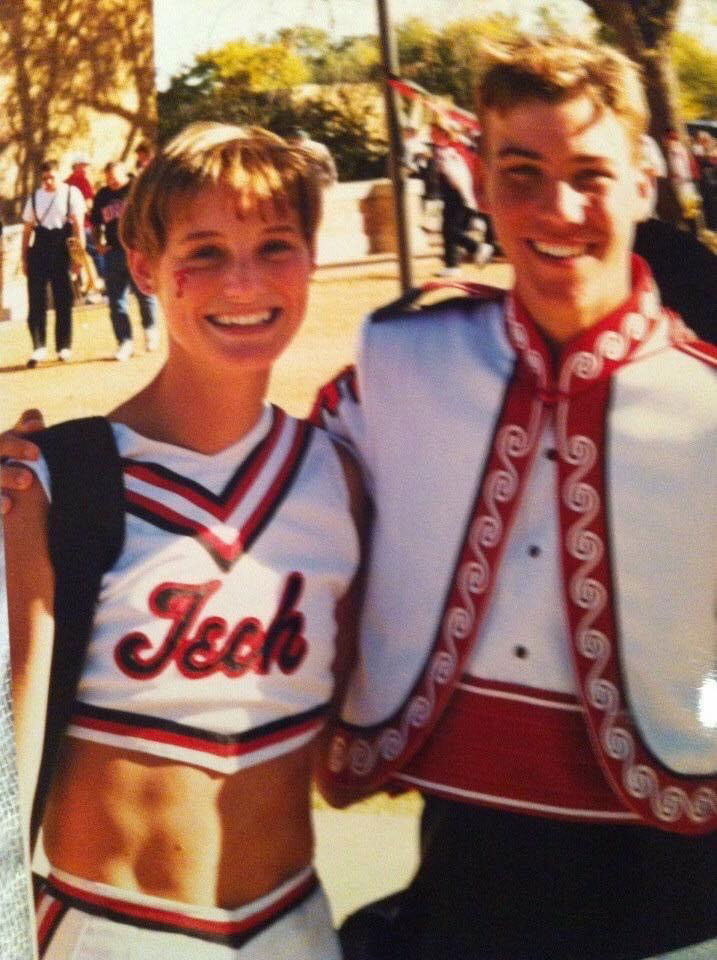

Both she and her brother Jay marched in the Goin’ Band.

Julie had attended Texas Tech’s Band and Orchestra Camp throughout high school. The summer before her senior year, she met a boy named Jeff and they hit it off (and not just because he shared the name of someone she had lost).

At the end of camp, they parted ways not expecting to see each other again.

To their surprise, Julie and Jeff both were admitted to Texas Tech and started in the Goin’ Band a year later. Sparks rekindled and they soon started dating. Julie played the flute and piccolo, which she loved. She also loved cheerleading. After her first year, she tried out for the cheerleading squad and made it.

She cheered full time but remained a part of the Goin’ Band, staying active in competitions.

Something else changed between her first and second year at Texas Tech.

Killion’s health took a turn for the worse in 1997. The last memory Julie has of her grandfather fully himself, was a band banquet he spoke at her first year.

“It was obvious his health was failing, but he was still so funny,” Julie recalled. “The students were excited to hear from him and he got so much joy from being invited.”

A few months later, he was gone.

Traditions

While the Goin’ Band lost a true pioneer and beloved community member, Killion’s impact has only grown since his passing.

There are many traditions Red Raiders enjoy today because of him.

“The fanfare the band plays when the Masked Rider runs down the field was dreamed up by dad,” Jerry said.

Killion felt the horse’s grand entrance needed a song of its own.

“He approached Richard Tolley and asked if they could compose something special,” Jerry recalled.

That same song will be played during the Macy’s Day Thanksgiving Day Parade, Killion’s legacy reaching the ears of millions.

The band grew from 50 members to more than 400 under the direction of Killion. He also was the inventor of the Band 1 and Band 2 formation, having mirrored instrumentation on both sides of the 50-yard line. This was done to ensure both sides of the stadium could hear the performance.

The band started traveling to bowl games in 1965, which is where the term “Goin’ Band from Raiderland” came from, another tradition started under Killion. The band’s Gator Bowl performances in 1966 and 1973 brought a flood of letters from around the country to Killion’s office, all praising the halftime show.

But the tradition Killion was most proud of was the one established in his own family.

“Dad would be so proud to see his great-grandchildren in the Goin’ Band,” Barbie beamed. “He passed away around the time his grandchildren made the band, so knowing they succeeded and now their children are succeeding, would make him very happy.”

A Legacy Honored

Julie and Jeff married after graduating from Texas Tech.

They have three children: Andrew, Ava and Jude.

Jude plays the piano. Ava is a dancer and hopes to join the pom squad at Texas Tech, and of course Andrew is now in his first year with the Goin’ Band.

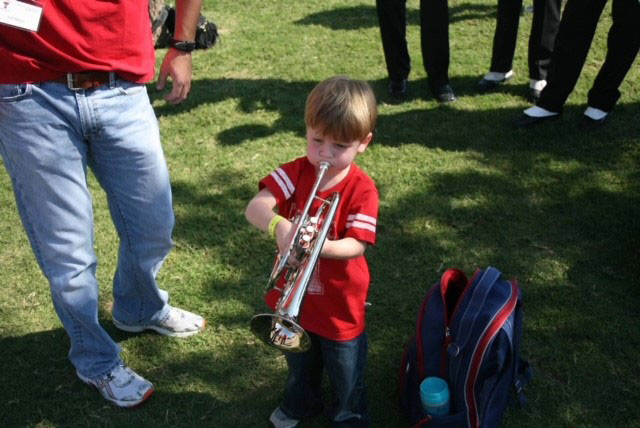

“My great grandfather was a trumpet player and so was my dad,” Andrew said. “It was all I ever wanted to do growing up – be a great trumpet player like them.”

Andrew attended his first Texas Tech game as a baby and hasn’t missed a season since.

“We’ve taken Andrew and our other kids to at least one game a season their whole lives,” Julie said. “We want them to participate in pre-game concerts and the walk over to the stadium.”

It’s not just a school tradition to them; it’s a family tradition, as evidenced in one of Andrew’s earliest memories.

“When I was really young, my parents took me to where the band was sitting at a football game,” Andrew recalled.

Julie and Jeff walked little Andrew up to meet the director at the time. He asked Andrew if he wanted to help conduct.

“Andrew was a very shy child, so I knew the offer, while kind, would not be accepted,” Julie said.

But Andrew did the unexpected.

“I just started climbing the ladder and got up there,” Andrew said, a smile on his face.

Andrew, just 4 years old at the time, had a bit of showmanship in him after all. Not unlike another family member who made his debut at a young age.

And on Thanksgiving Day, Andrew will be the one to fulfill another milestone for the Killion family. Barbie, James and Jerry, along with all the grandkids and great grandkids will be cheering on the Goin’ Band from Raiderland as they appear on NBC.

“I never got to meet my great-grandfather, but I think he’d be really proud of the band this year,” Andrew said. “I know I am.”

Dean Killion’s great-grandchildren include:

Andrew Meyer, trumpet

Ava Meyer

Jude Meyer, piano

Bailey Newton, trombone

Blake Newton, trumpet

Barrett Newton

Charlotte Wilson

JJ Wilson

Reid Damiano

Kamryn Damiano

Sam Damiano

Anna Sparks

Taylor Tolson

Tripp Tolson

Turner Tolson

Dean Killion

Joe Killion