Hannah Roehr is an award-winning artist but she’s most proud of how she’s added to the legacy of Texas Tech’s School of Art.

The art of printmaking is both calculated and full of surprise.

Artists go to great lengths choosing the right matrix, the right ink and selecting a breathtaking image to print. But when the pressing comes, you never quite know what will come out.

“There’s definitely crying in printmaking,” said Hannah Roehr, a fourth-year student in the School of Art.

Hannah has shed tears over images that didn’t work out as she hoped. She spent two years working on technique before she created anything she deemed beautiful.

Draw, ink, press, repeat.

She experimented with different matrixes to discover which one would mimic how she felt inside. Years into the process, she’s become partial to lithography, one of the more modern matrixes in printmaking.

Lithography is based on the fact that oil and water don’t mix. Hannah is acutely aware of polarities that don’t mix well.

Oil and water.

Chaos and peace.

Safety and growth.

But in her time at Texas Tech University, she’s discovered that two polarities can, in fact, exist together – grief and joy.

Staying Inside the Box

It’s an afternoon in April, and Hannah is a few weeks away from graduating with her Bachelor of Fine Arts in Printmaking. She’s wrapping up a few final pieces, carefully prepping a stone slab with ink.

As effortlessly as Hannah traces lines onto the stone, this didn’t come naturally to her. Nor was it the career she expected to have.

Hannah started college as an art history major but quickly grew bored. She wanted to leave college, but her parents made it clear if she wasn’t attending school, she’d need to work. This sounded like a fine idea to Hannah, and after a few entry jobs, she found herself climbing the corporate ladder in human relations.

She went to work for Indeed, Inc., as a corporate recruiter. The job suited her well. She thrived on multitasking multiple projects in a fast-paced environment.

“I’m very organized,” she said. “I like boxes and rules.”

It was for these reasons Hannah determined art might not be a good fit for her.

Then her world turned upside down. Her mother was diagnosed with ovarian cancer in 2017.

Her mother’s diagnosis came as a complete shock. With parents who were separated, Hannah stepped in as her mother’s fulltime caretaker. This meant quitting her job, attending dozens of doctor appointments, and moving in with her mother.

Hannah recounts this time as precious, with no trace of bitterness in her voice. She points to one of her prints; it’s a sketched image of a hospital waiting room.

“That’s my ‘save file as’ mentality,” she said. “Like in a video game, where you can pause in the middle of a story and come back to a particular moment. I wondered what moments I would go back to when my mother was battling cancer.”

She says her mother was in and out of the emergency room 17 times in one year alone. Hannah spent a lot of time in waiting rooms. Even though they’re known for their lackluster décor and cold temperatures, waiting rooms became a constant companion to Hannah.

“This print is my way of saying ‘This was so hard, but I’d still go back,’” she said.

An Empty Studio

Hannah’s mother entered remission by the end of 2017 and the experience left Hannah looking for a deeper sense of purpose. While an art history program had not suited her, Hannah’s love for art had never gone away. She made the decision to return to college and enrolled at Minot State University in North Dakota. She took her first printmaking course and fell in love.

“Printmaking is a very process-oriented medium,” she said. “Some of the art forms I’d tried were open-ended, and I don’t do well with those. I like knowing where I am going, and I like working within specific parameters.”

Hannah could envision building a career in printmaking; she felt she had positive momentum for the first time in years.

Then her mother’s cancer came back in 2018.

The cancer was aggressive, and Hannah’s mother could not manage living on her own. Eventually, Hannah helped her pack up her medical practice, and they moved to Texas. They had extended family in Grand Prairie, where Hannah was raised. Her mother began treatment for a second time. With more support from family, Hannah was not in the position of being her mother’s only caretaker. She did not want to lose the momentum she’d just found, so she decided to transfer to Texas Tech.

“I talked to a family member in higher education, and they told me if I wanted to do printmaking, Texas Tech was the place to go,” Hannah said.

They told Hannah of Lynwood Kreneck’s legacy and the program he had built at Texas Tech. While Professor Kreneck retired from teaching many years ago, the printmaking faculty at Texas Tech remained strong.

Hannah began school at Texas Tech in the fall of 2020. While uncertainty from the pandemic swirled around her and she constantly worried about her mother, Hannah felt at home on campus. She slowly built a new community and immersed herself in printmaking.

At the end of her first semester, her mother took a turn for the worse.

“Unfortunately, she passed away at the end of the year,” Hannah said, eyes filled with restrained tears.

Hannah almost quit school.

“I had no idea how I would go back to school grieving and do good work,” Hannah recalled.

Fortunately for Hannah, her father knew her well enough to know she needed to have an outlet, something to do. He told her she would be more miserable sitting home, that she would become bored, and he worried what that might do.

Hannah returned to Lubbock at the beginning of 2021, broken-hearted but willing to finish what she started. Around the same time as her mother’s passing, the coordinator of the printmaking program and associate professor, Stacy Elko, also passed away. This left her colleague, Professor Sangmi Yoo, devastated.

“It was a very difficult time for me and the print program as we were unprepared for her sudden departure, especially at the onset of COVID-19,” Yoo recalls.

The printmaking studio was cluttered and chaotic. Elko, like many printmakers, had been a bit of a hoarder. The studio needed a fresh start, much like Yoo and Hannah.

Yoo became Hannah’s professor and mentor. She quickly noticed Hannah’s knack for organization and asked if she’d be willing to help her clean out the studio. Hannah looked over the stacks of handmade papers, prints and woodcut blocks glad to have a project to distract her.

Together, the two women sorted through the aftermath of Elko’s legacy. Some prints brought smiles, others prompted a story. Sometimes they worked in silence.

The studio had to be ready for new work.

Grief & Growth

Texas Tech was where Hannah needed to be in the months following her mother’s passing, she says.

“Through my prints, I was trying to address the things that controlled me,” Hannah said. “I looked at my fears and how I confront them. I wanted to look them in the face.”

Hannah didn’t want to hide in her grief. She allowed her emotions to move through her like ink transferring from one surface to another. Hannah says she saw her early work as fragile. She was focused on form more than function, even though printmaking can be both.

“I was stuck in the square of printmaking,” said the former rule-loving artist.

All the boundaries and safety nets she originally loved about the artform, became something to challenge as she grieved.

“There’s a safety to knowing how to get from point A to point B,” Hannah said.

But that turned out to not be true about the artform she had fallen in love with. The medium that had mesmerized her with its seemingly strict methods, was actually much more.

In her words, Hannah became less “precious” about her work. Not everything had to be picture perfect. Over time, she began experimenting with installation prints (more akin to wheat-pasted posters) that are destroyed once taken down. This would have devastated her in her earlier years.

“Because I am so order-focused, it took me a long time to break that order,” she said. “I realized there can be a real chaos to printmaking.”

This side of the practice may have taken Hannah longer to lean into in the absence of grief. Grief is chaotic. It’s a force that demands acceptance before it can be understood.

Some of Hannah’s prints have taken 40 or 50-plus hours to create. The amount of time spent on a singular work tempts her to see the work as precious, and it is. But she’s learning preciousness isn’t just in form, but in fleetingness.

As COVID restrictions lifted in late 2021, the School of Art’s Tech Print Club was resurrected. The club had dissipated during the pandemic and its previous leadership had graduated. The group needed a leader. Hannah was already a student assistant and was teaching high school students through the school’s summer immersion program. Taking on print club was a natural next step.

She’s held the position for the past three years.

“Hannah has created a very positive and inclusive environment for our program and beyond, connecting students from every background,” Yoo said. “With mature understanding of her peers, she has been integral in building a sense of community in the School of Art.”

Hannah’s studio mate Destanee “Riot” Brock has been brought into Hannah’s fold. Riot, a year behind Hannah, will be taking on more leadership with the print club next year. Riot jokes that while Hannah has become less structured in some ways, she still left the incoming officers with many pre-formulated spreadsheets to maximize efficiency.

Riot has shared studio space with Hannah the past two years, providing time for the students to get to know one another.

“She’s willing to talk about the hard stuff,” Riot said. “There is artwork she’s done about her mom for critiques and that takes a lot of vulnerability.”

It’s something Riot admires about Hannah.

“When my brother passed away in 2022, Hannah was someone I could talk to about that,” they said. “She helped me process.”

For Hannah, printmaking isn’t about art alone. It’s also a vessel to connect with others. Her time at Texas Tech has provided her opportunities to build meaningful relationships with peers and faculty.

It’s also allowed her to educate the public on the importance of printmaking. This is one of the goals of print club, and it’s something Hannah has championed. Since 2021, the club has returned to the First Friday Art Trail. Their activities are held in the Charles Adams Studio Project (CASP) print studio that can be found easily during trails.

“I love seeing people figure out what they’re looking at, or trying to guess,” Hannah said. “I love helping them solve the mystery and explain each process in detail.”

Releasing Chaos

It is a detailed process.

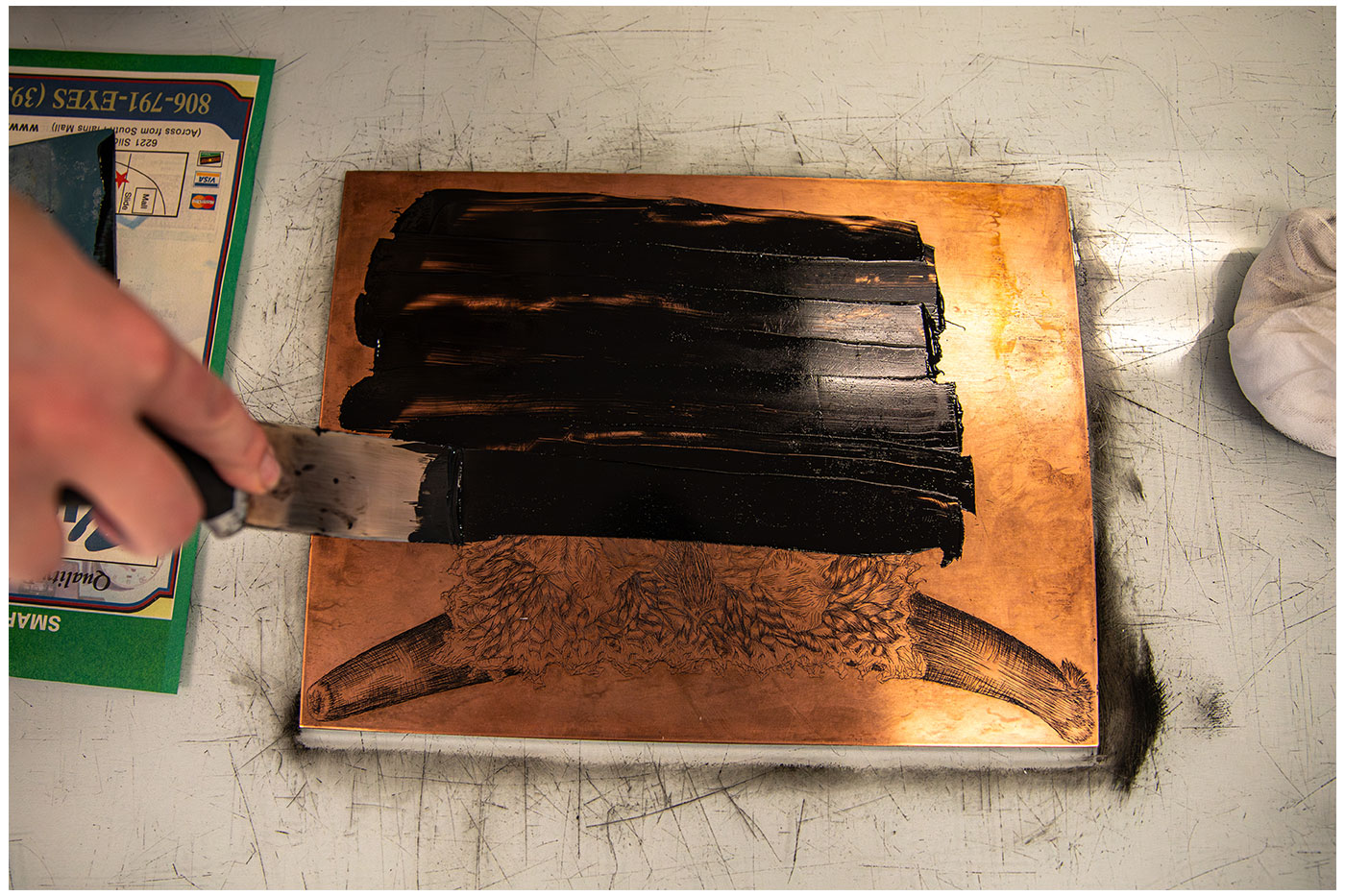

As Hannah explains, each printmaker starts with an image. This can be drawn, painted or engraved onto a surface used to transfer the image. The next step depends on what kind of printmaking one is doing.

There are four major kinds: relief, intaglio, lithography and screenprinting.

This matters because the matrix used to transfer the image varies depending on which kind of printmaking is being done.

Some are done with wood through carving, others with metal via etching in the acid. Some are digitally created on a photo-sensitive surface.

Hannah has become partial to lithography. She starts her images with pencil or tusche (a greasy watercolor) and then applies it to a flat slab of limestone. When pressed, it carefully fills the stone’s pores. A chemical mixture is then used to bond the stone before water fills the remaining pores.

When Hannah “inks-up” as it’s called, the ink is attracted to the areas of the matrix that retain that pencil or tusche because of the grease.

The process is as scientific as it is artistic.

It also means things can go wrong. Hannah points at a print of caves in Southwest Texas she did last year. To the untrained eye it’s stunning, but she’s still haunted by the negative space that didn’t transfer.

She moves down the table to a piece she proudly talks about. There are three prints that go together in a series. The first is of a crotched square stretched like a hide. The second is a bull. The third is a rose garden.

The images might sound familiar to anyone who’s read Flannery O’Connor’s “Greenleaf.” Hannah is drawn to stories like these from her love of mystery novels and Southern Gothic shorts, interests she and her mother shared as soon as Hannah was old enough to read Nancy Drew.

“I’m a cheery person but I like focusing on dark stories,” Hannah admits. “They help balance things out. A lot of stories we read have happy endings, but in life that doesn’t always happen.

“I think this is my response.”

Greenleaf tells the story of Mrs. May whose pristine garden is being torn up by a stray bull. The creature starts with Mrs. May’s hedge but eventually moves onto her prized roses. Mrs. May spends the entirety of the story fighting an immovable force, desperately trying to save the beauty of her roses.

In the end, her frantic chase ends with the bull impaling her with its horns.

“It’s a story about chaos, and I feel that’s what I am trying to embrace,” Hannah said.

She took the print of the bull and made a wallpaper installation in one of the School of Art’s hallways. It will be ruined when it’s taken down. It’s Hannah’s way of letting go a bit – of wandering outside the square of printmaking.

A Printmaker Extraordinaire

After commencement, Hannah will attend graduate school at Louisiana State University where she’ll continue her education in printmaking. After that, she hopes to either do master printmaking or teach at the university level, or perhaps both.

“It would be a natural move for Hannah to pursue a career in printmaking and to share her knowledge with larger communities in higher education,” Yoo said. “I consider Hannah to be a printmaker extraordinaire and a remarkable student from our program.”

Yoo nominated Hannah for the Southern Graphics Council International (SGCI) Undergraduate Fellowship which she won in 2024. And befittingly, Hannah was awarded the Stacy Elko Memorial Medici Circle Scholarship in 2023.

Hannah will finish her undergraduate career in her 30s, and she wouldn’t have it any other way, she says with a joyful grin.

“I don’t think I was ready for school in my 20s,” Hannah said. “Now, I know how to be responsible for the things I care about.”

Hannah’s maturity allows her to embrace life’s contradictions, which is something artists spend a lifetime trying to understand.

“You have no idea how a print will come out until you press it,” Hannah said. “But when you have a moment where everything fits into place, it’s magic.”