Niramay Gogate and an interdisciplinary scientific group see their findings from work in India published in Nature’s Scientific Reports.

As the COVID-19 pandemic ravaged his home country of India, Niramay Gogate helped lead an international team of young scientists from interdisciplinary backgrounds to better understand the pandemic using data. The team was part of the Jnana Prabodhini Foundation (JPF), a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization with its work supported by Johns Hopkins University and Carnegie Mellon University.

Gogate, a doctoral student in the Department of Physics and Astronomy at Texas Tech University, was particularly interested in the accuracy of officially reported COVID-19 deaths. This data was provided by the Pune Knowledge Cluster, a Science and Technology Cluster under the Office of the Principal Scientific Adviser to the government of India. The team’s goal was to analyze available data and reach conclusions that could be important in the event of a subsequent pandemic.

The 21-person team recently had the findings of its work published in Nature’s Scientific Reports. Gogate served as one of the lead analysts and a research coordinator within the team during the paper’s review. The group’s work is titled “Conventional and frugal methods of estimating COVID-19-related excess deaths and undercount factors.”

The research represents the first systematic study using a multi-method approach for estimating COVID-19 deaths in Pune, one of the largest metropolitan areas of India with more than 7 million residents. Like the rest of the country, it was hit especially hard by several waves of the virus. Between Jan. 1, 2020, and Dec. 31, 2021, Pune officially reported more than half a million COVID-19 cases and 9,093 COVID-19 deaths over two successive waves.

Despite a huge number of officially reported cases and deaths, Pune is one of the few large Indian cities for which pandemic-associated excess mortality has not been determined.

“When we first embarked upon our research journey, the COVID-19 pandemic was also in its nascent stages” Gogate said. “Most of us were already engaged in scientific research in our professional lives, and so were quite familiar with statistical methods. The idea was to bring together young scientists from all over the world who had a connection to India and Pune, and thus were personally affected by the problems emerging from the pandemic. Our aim was to understand and solve a socially relevant problem in India, namely the lack of accurate and trustworthy data about the pandemic. Such data is critical for understanding, mitigating and preventing public health crises.”

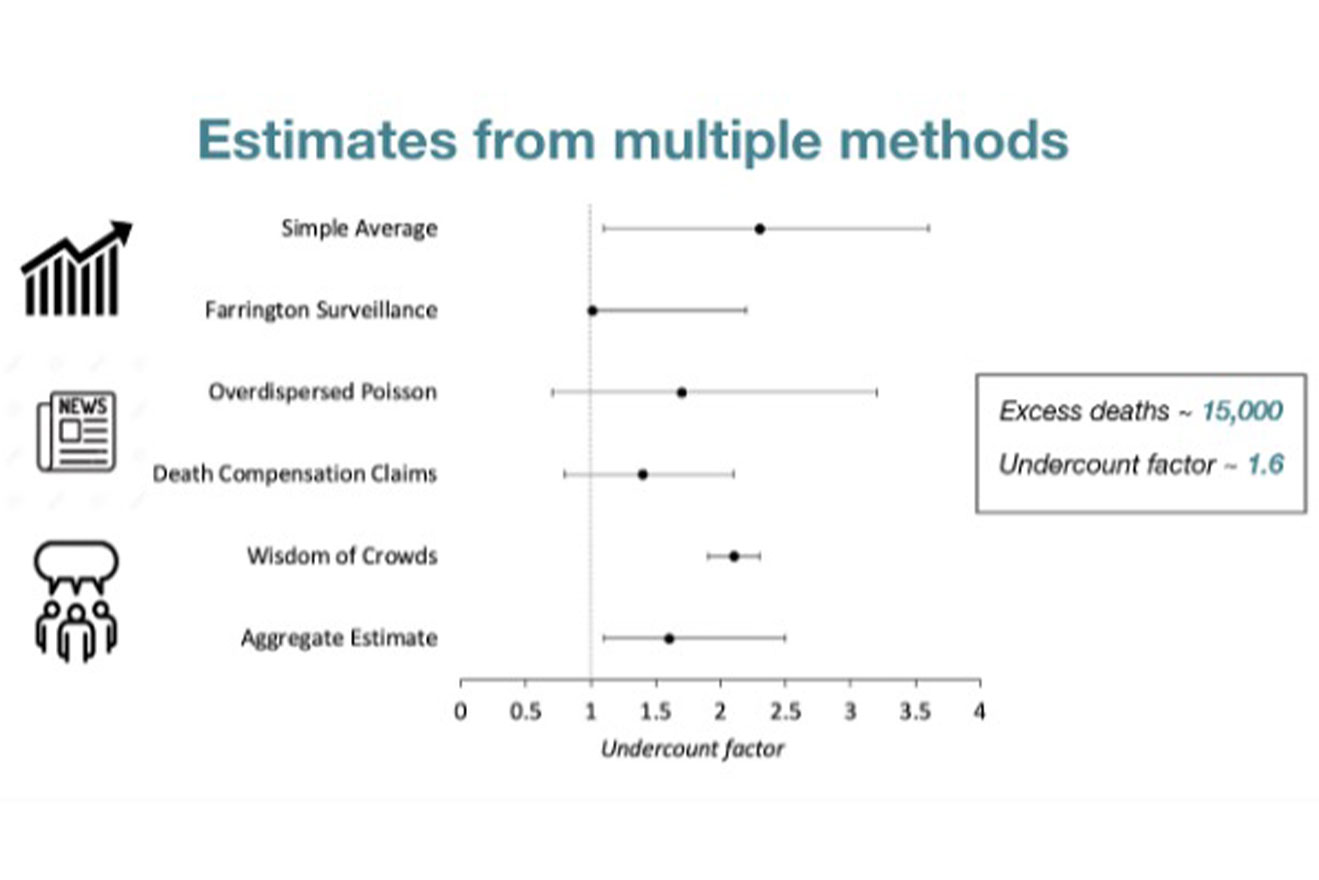

Across the world, including in Pune, there were widespread concerns about the lack of reliable death estimates during the pandemic. Skepticism about official COVID-19 mortality data arises from a lack of rigorous testing, absence of medical certification, deaths occurring outside formal health care systems, and other indirect pandemic-related deaths that occurred due to delays or lack of access to health care, reduced hospital capacity, increased risk of other diseases, and post-COVID-19 complications. The team used integrated findings from three different methods: statistical modeling, analysis of death compensation claims and public surveying.

They used these methods to predict COVID-19-related mortality in Pune. In addition to conventionally validated methods of estimating COVID-19 mortality, the group used a novel approach, namely the “wisdom of crowds” surveying. The method refers to the counterintuitive accuracy of aggregated public opinions.

“We gauged and quantified public opinions about COVID-19-related beliefs and behaviors, including vaccine skepticism, mask usage, perceived fear of the pandemic, etc.,” said Gogate, who now is conducting his doctoral research at CERN, the European Laboratory for Particle Physics in Geneva, Switzerland. “Importantly, we asked the public to estimate the ‘true’ number of COVID-19-related deaths in Pune.”

Results from various methods all pointed toward a similar conclusion – almost twice as many pandemic-related deaths compared to official statistics.

“This work demonstrates that rigorous research can be conducted on issues of social importance such as public health policy with the voluntary participation of people from diverse academic backgrounds,” said Sung-Won Lee, chairman of the department of Physics & Astronomy in the College of Arts & Sciences.

“They drew meaningful conclusions using sophisticated statistical modeling techniques and cost-effective frugal methods, and their findings are expected to influence future health policies.”

The group’s findings were validated when the government offered monetary compensation to families who suffered the loss of loved ones during the pandemic. The ensuing claims far outdistanced the official death totals.

Gogate and the researchers also compared the survey numbers to statistics reported by news outlets and other organizations, which also demonstrated a wide discrepancy.

“The point of the work was not to criticize the government,” Gogate said. “The point was to build credibility for estimated deaths in India during the pandemic and prepare the government for the next one, in case there is one. Even some of the world’s best health care systems underestimated COVID-19 deaths to various degrees. Based on our results, Pune’s performance in this regard seems comparable to some of the leading health care systems across the world, with its public health data recording infrastructure proving to be fairly robust and resilient during the COVID-19 pandemic.”

Much of the team’s work took place in 2022 between two equally devastating waves of the virus throughout India. It was challenging because virus-related restrictions were still in place, making it difficult to survey people face to face or in their homes.

“Niramay made a significant contribution to the non-physics subject by actively utilizing the expertise gained from his Ph.D. research in high energy physics,” Lee said. “I, as his Ph.D. adviser, am very proud of Niramay for being such an active and self-motivated interdisciplinary researcher and applaud him and his team for the scientific achievements they have made.”

The researchers were assisted in the survey work by numerous nongovernmental agencies, and they received almost 3,000 responses on which they built their statistical blueprint. It took about three months to compile data once the survey closed.

“India was hit hard by COVID-19,” Gogate said. “The whole point of talking about an undercount is to see how well prepared the government is when estimating pandemic impact. It is OK not to have 100% accuracy, but if you know the undercount factor ahead of time, you can be better prepared for the next one.”

For example, the Pune work revealed a dramatic undercount. The researchers’ data indicated if a government projection suggested 1,000 deaths, it would be more realistic to plan for closer to 2,000. In addition, to prepare for future pandemics, resilient public health systems require sustained material investments in vital infrastructure and medical equipment, as well as the availability of credible, open-source, and high-quality data. The success of these initiatives will depend on both long-term material investments in vital infrastructure and medical equipment, as well as the availability and abundance of credible, open-source, high-quality data.