Growing up in poverty, Lizzy Johnson found her happy place in school.

As the only child of divorced parents – an alcoholic biological father who drifted in and out of the picture and a mother with limited education who struggled to pay the bills – data and research would say there is no rhyme or reason why Lizzy Johnson should have even graduated from Texas Tech University, let alone earn a doctorate, run a company or have much of any success.

Growing up in poverty, the odds were certainly against her.

Poverty can look different to different people. For Lizzy, it was sometimes not having meals or groceries, except for the kindness of people who cared about them. Her mom was a clerical employee, not making much money, so they were poor and needy much of the time, and they moved a lot. Many times, Lizzy’s mom would make the rent, but then not the next month or the next.

“Like a lot of kids of poverty, we didn’t have a lot of possessions,” Lizzy said. “So, when we moved, it was basically put your clothes and anything you can in a car that we had, and we would move on to the next place; we stayed with family a lot. Much of it was situational because of low education, and just not a lot of ways to get ahead for us, in Mom’s mind.”

At some point, Lizzy’s mom began working for one-time leading retailer Montgomery Ward as the scheduler in the repairs department. It was there her mom met one of the repairmen and called on him to come fix a kitchen appliance. Young Lizzy was watching. He seemed to be a nice man with a job – and stability – and Lizzy herself invited him back over. When Lizzy was 10, her mother married him, and because of two working-class incomes, life improved significantly.

In fact, they moved into a home that Lizzy lived in from fourth grade until she graduated from high school, the longest she had ever lived in one place. She can’t recount all the places she lived; it was so many. But, Lizzy says, living in that situation, “We all try to find something to give us hope.” Lizzy’s hope was school.

“School was safe, and there was food there, and the teachers were kind, and so I gravitated toward that being my happy place,” Lizzy recalled, her eyes misty with the memories. “And I think that’s one reason why I’ve become such an advocate for public education, and even followed that in my career.”

Teachers helped Lizzy realize what happened in the past didn’t have to dictate the future. It was, perhaps, foreshadowing that educators stepped in and took over when Lizzy did not have resources and support.

Forging a Path to College

Lizzy was told “You should go to college,” and “It’s going to open more doors for you.” But as someone who didn’t have anyone modeling that in her life, it was more like, “Best of luck to you.”

In high school, she talked to influential teachers she knew. She vividly remembers these people and starting conversations with them because she knew they had gone to college. It wasn’t so much school counselors, but it was more like, “Hey, Mr. Mack? Tell me about college. Like, how does that work? What do I do?”

In addition, colleges would come to her school for recruiting fairs; Lizzy would go to the sessions and just listen. From those, she felt she was getting the hang of this college application thing. Fill out this form, do this and complete that.

Instead of leaving San Antonio for her first year of college, Lizzy stayed because she was so new to it all. She didn’t even know she could go away; she went to the University of Texas at San Antonio and waded her way through a freshman year of trial and error.

“I was a pretty good student in high school, but, as you know, college is different,” Lizzy said, chuckling, "and especially when nobody in your world has ever done it.”

The Road to Texas Tech

Once through that first year, Lizzy wanted to try college away. She felt the need to get out of her comfort zone because what she knew of comfort was people who stayed in that same cycle and never got out. What she wanted more than anything was to find the courage to go away to school and start that chapter of her life.

Lizzy’s best friend Teri, who went to high school with her, also stayed in town that first year. Then they plotted to go elsewhere.

“We got a map out, and said, ‘The farthest we could go away from our city,’ so we won’t want to go back, and so our parents are not dropping in; there were multiple reasons, right?” Lizzy explained with a grin.

The University of Texas El Paso was a choice, as El Paso is far from San Antonio. But then Lubbock and Texas Tech came up.

The two young ladies got in the car with their moms one day and made the nearly six-hour drive to Texas Tech. They did about an hour tour, drove around a little bit, got back in the car and returned to San Antonio.

“Man, this is far, you know. Are you sure?” Lizzy’s mom queried on the way home.

Lizzy didn’t miss a beat. “Oh, I’m going there. I’m doing this!”

Lizzy and Teri each filled out a simple two-page college application on paper. In 1991 nothing was online. There was no essay. Lizzy said the university basically just wanted “an address for where to send the bill and your social.” The two sent in that information and were accepted, packed up in the summer, put everything in Teri’s car – Lizzy didn’t take a car to college – and drove to Lubbock. Arriving two weeks before classes started, they moved into a dorm and were excited to begin the next chapter – away.

Riding High as a Red Raider

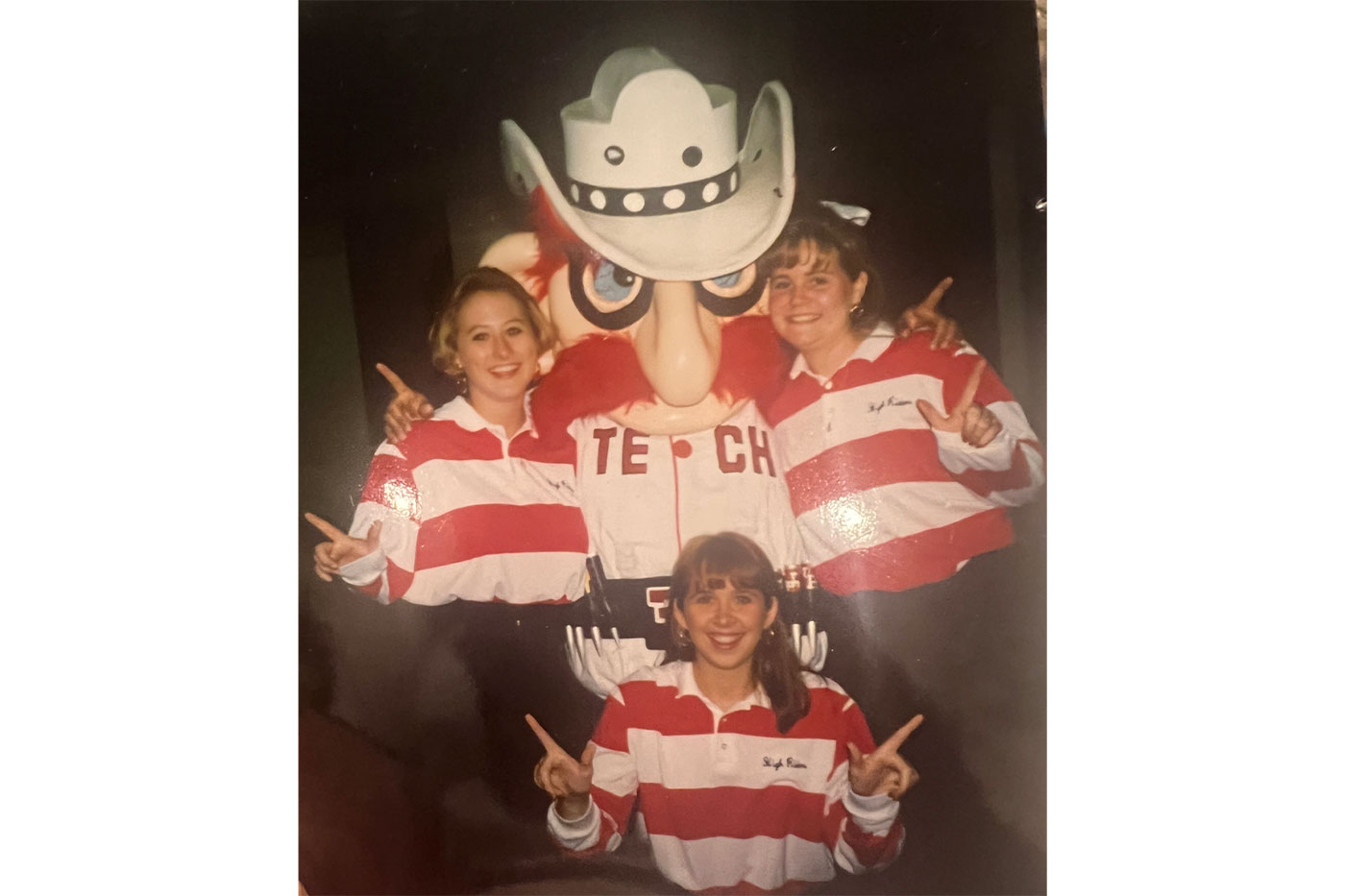

Being so different from San Antonio, Lubbock was exactly what Lizzy says she needed, and Texas Tech was perfect for her. The university wasn’t so big that she could get lost in the shuffle, and there were groups to get involved with. Lizzy was a High Rider, the women’s spirit organization that supports all women’s sports and a few of the men’s programs. She loved being a High Rider, for which Joyce Arterburn (“Mrs. Art”) was one of the founders and a driving force in all the girls’ young lives.

“She was a Texas Tech treasure, a surrogate mom to all of us; she made the best popcorn and had solid advice for any college student. She and her husband Junior were amazing,” Lizzy recalled. “And so, we found places to connect, and we found people that we connected with. I met my very best friend Libby at a High Rider meeting.

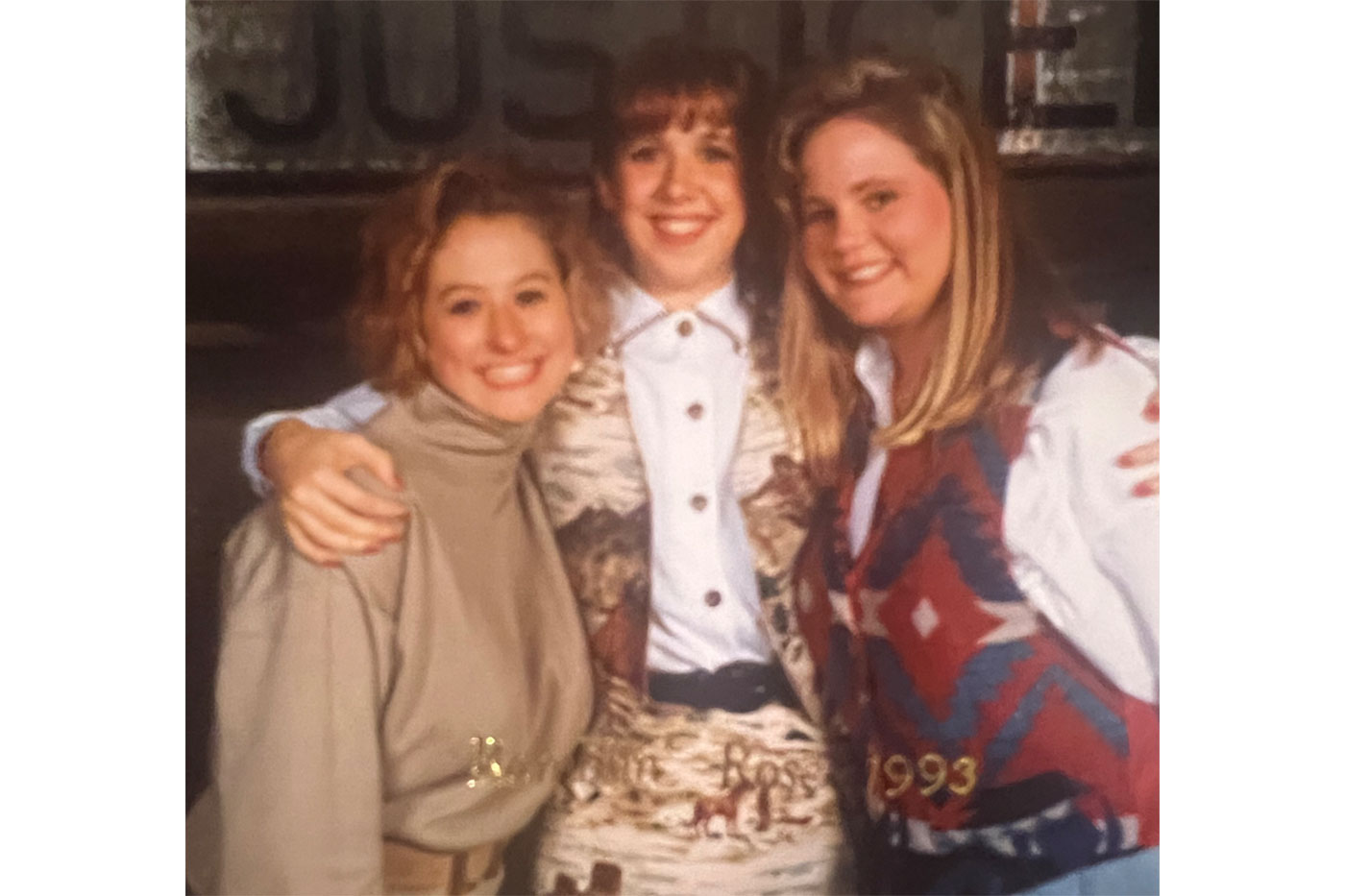

“She walked into a recruiting/orientation meeting late and she goes, ‘I’m late, but I’m here, and we can get started!’ I looked over at Teri and I said, ‘We’re going to meet that girl; we’re going to be friends with her.’ And that was it. Ever since then we’ve been linked at the hip. She is my best friend, and we’ve been friends since 1992. We’ve been through ups and downs and have even raised our girls together.”

Being in High Riders allowed Lizzy to do things like give campus tours, attend women’s athletics events, even the early, cold, cross country meets; and, best of all, the Lady Raiders won the NCAA women’s basketball national championship in 1993 while Lizzy and her friends were there.

“When the Lady Raiders came home, they rode into the Jones Stadium in a limo, and all the High Riders were there to greet them and welcome them home. It was amazing,” Lizzy said with a wide grin, her eyes sparkling with the memory. “We rang the Victory Bells late into the night when they won, and we even got in trouble – President (Robert) Lawless had to come up to the bell tower to tell us to stop! We were so pumped!”

Lizzy continued, the memories spilling out unfettered, as if it were yesterday.

She and Teri lived in Wall/Gates Hall when it was a women’s dorm and walked every bit of campus before school started in 1992, since they moved in the first day they could.

“We loved watching the Saddle Tramps (the men’s spirit organization) wrap Will Rogers and Soapsuds the night before football games; and of course, we attended every game while attending Texas Tech. Zach Thomas was playing football and Spike Dykes was the coach. Zach’s famous interception during the Tech-A&M game in 1995 was one of the most amazing things I have ever seen at a college football game. The entire stadium jumped when he took that ball into the end zone.

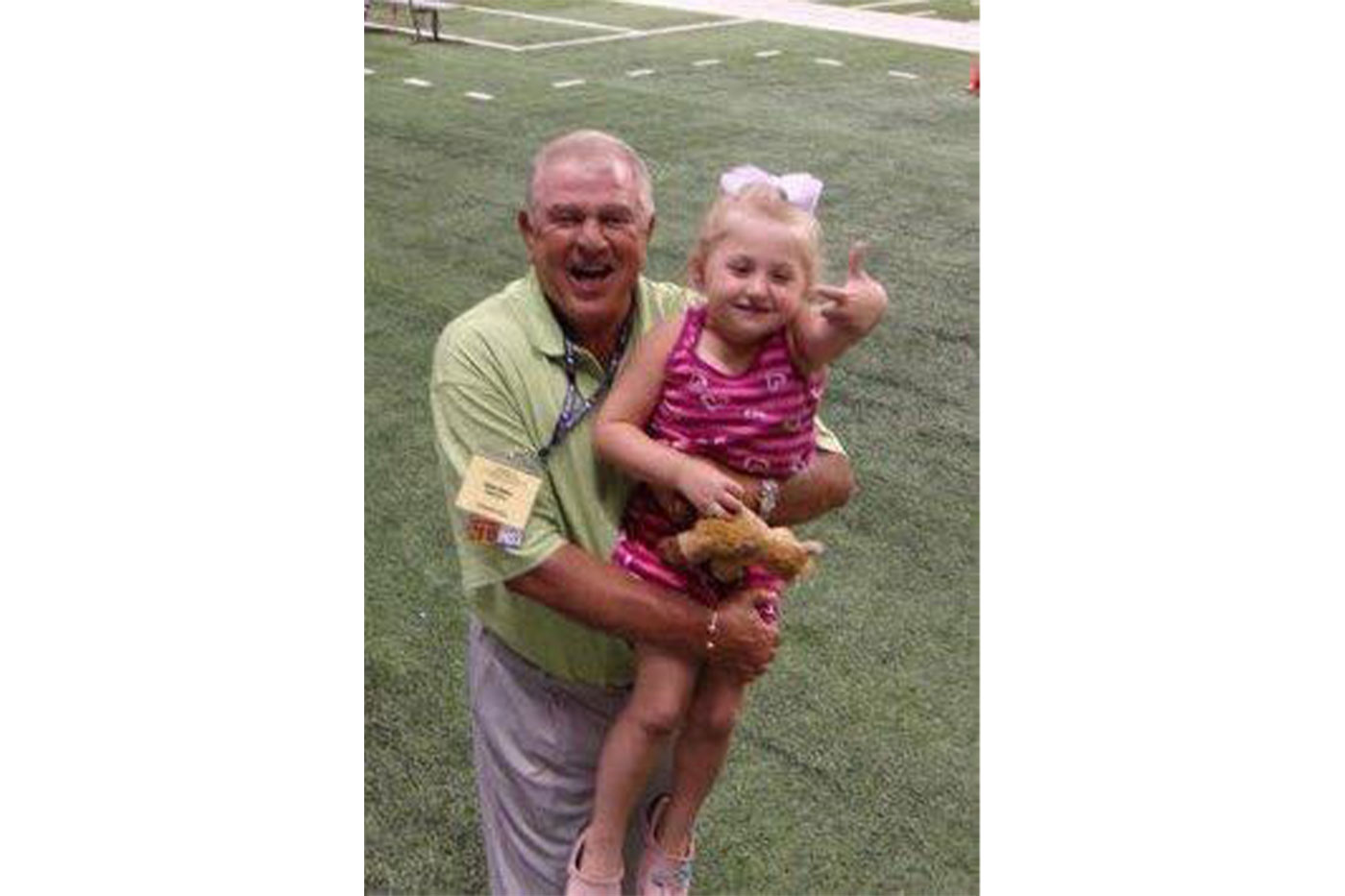

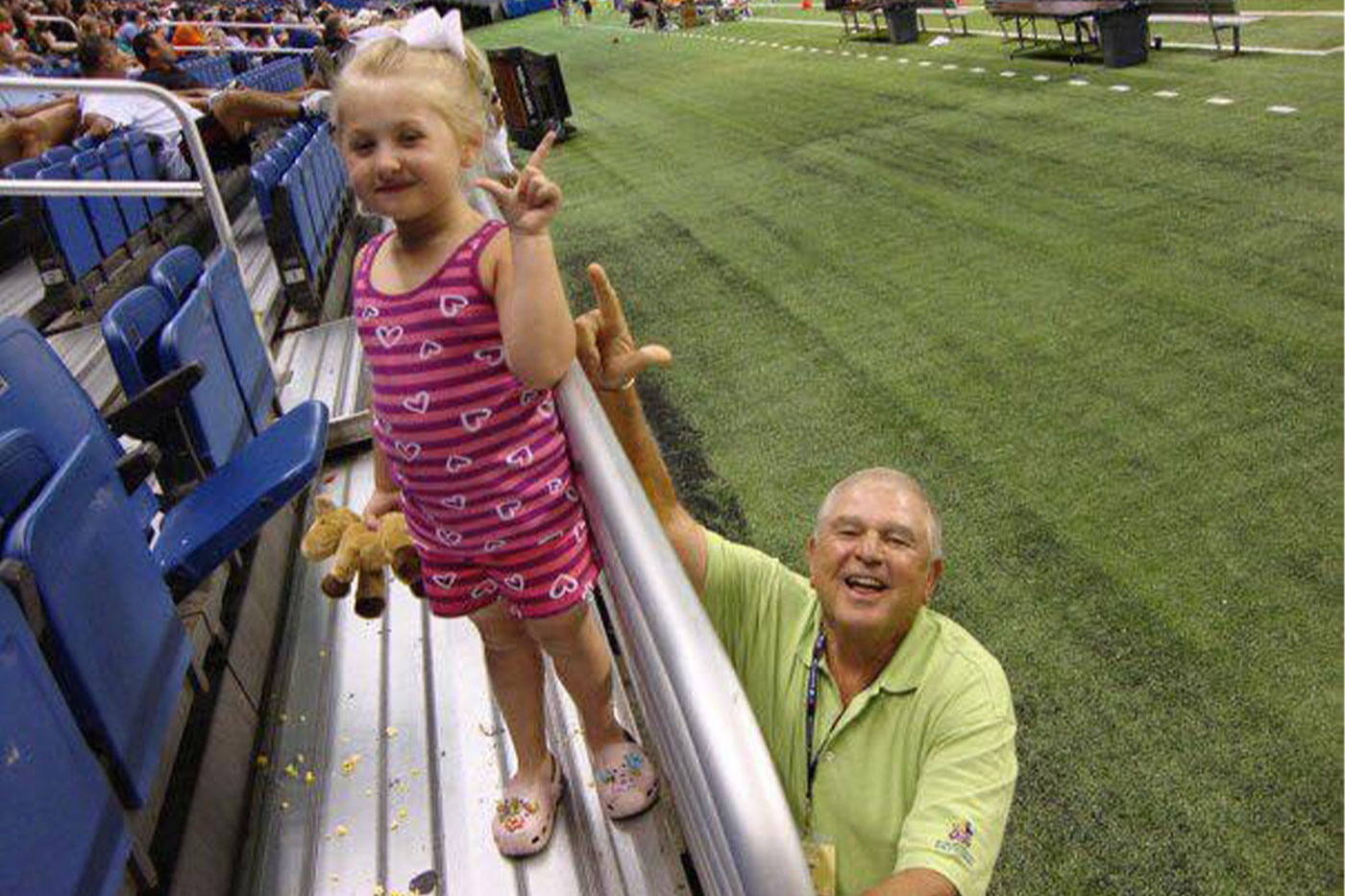

“On the subject of Coach Dykes, we ran into him the summer of 2009, and he had me lower Kloe (Lizzy’s daughter) down onto the field so he could walk her around and teach her how to ‘get her Guns Up.’ It was so cute.”

Lizzy says being at Texas Tech really opened her eyes to other people from around the nation and around the world. She also had amazing professors who knew they were molding the minds of young students. They were always accessible and supportive as Lizzy and her friends worked through their degrees and studies.

After graduating with a major in history and minors in education and sociology in December 1995, Lizzy did her student teaching in the spring of 1996 at Monterey High School in Lubbock, where she encountered inspiring mentors and educators. She moved to the Dallas-Fort Worth metroplex and started teaching in the fall of 1996.

Perpetuating Encouragement

After a teaching career, Lizzy became a campus and district-level administrator for many small rural school districts, suburban mid-size and urban districts. One of those was in Celina, Texas.

That’s where Lizzy met Kallie (maiden name Barley) Covington.

“My dad was president of the school board of Celina when I was in high school, and so I would go to the admin building often, once or twice a week, to pick up different things for him, and that’s where Lizzy’s office was,” Kallie recalled. “I guess I kind of started just telling her hello and popping in. Over time it turned into this relationship where I would go to her office, and she would basically mentor me. She eventually left Celina to go to another high school in another district, but we still stayed in touch.”

That’s how Kallie got to Texas Tech; you see, Lizzy was a big force in how and when Kallie came to scout out a master’s program in mass communication. And throughout that degree process, Lizzy continued to support Kallie with a simple, “Hey, you’ve got this,” or, “You can do this!”

Then came the doctoral decision.

“I remember calling Lizzy,” Kallie said, jumping into another chapter about her mentor. “I was working at the Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center, and I said, ‘You just got your doctorate from UNT, and I think I want to do this at Texas Tech.’”

In her typical style, Lizzy explained to Kallie how glad she was that her friend and advisee was going to stay at Texas Tech for her Ph.D. in media and communication. And again, they stayed in regular contact through Kallie’s graduate study.

Building on Experience

Lizzy began her teaching career as a middle school history teacher and high school swim coach in Denton, Texas. She earned both her master’s and doctoral degrees in Educational Leadership from the University of North Texas. Throughout her public education career, Lizzy had seen many different ways of doing things. One thing she never saw was a five-year pin. She never stayed in a district long enough to earn one. She describes herself as the kind of person who would come in and find the gaps, fill them and pack it up. Lizzy was able to do that and leave systems in place where someone else could just come in and take over.

“I was a change agent,” Lizzy said, a serious look crossing her face. “What happened was I would get to the point where I had put all the items in place to do the change; and then you kind of have to leave after that because you’re not the most popular gal in the room at that point.”

The last stop in her public education career was the Region 10 Education Service Center as the director of administrative services. Her whole team was responsible for every administrator in the Dallas area. And, she said, “It was a lot.”

Lizzy loved what she did, but during that time, she started realizing she had a lot to offer outside of an organization: she could problem solve, project manage and help districts with things they didn't always have staff to initiate.

“And plus, third-party validation is pretty powerful,” Lizzy asserted. “I can walk into a room and tell a group of people you need to do XYZ, and they truly listen and get to work. It's different from someone within who could relay the same message.”

During her time at Region 10, and after she had finished her own doctorate, Lizzy kept feeling like there was more she could do. Opportunity presented itself, and that’s where her company, TransCend4, grew from and was launched in 2018.

Transcending Trends

Lizzy explained that, looking back, she sees how every role she took on prepared her to start her company. She learned the inner workings of education at the district, regional, state and federal levels, and how each impacts students, teachers, staff and administrators. Lizzy started TransCend4 to work with leaders at all levels to ensure every student receives a quality education.

The “four” stands for collaboration, communication, critical thinking and creativity. She works with school districts, educational leaders and organizations that provide services to schools mostly in Texas, but the company is beginning to expand in other states this year.

She starts each project with one goal in mind: How can we help clients create an exceptional school, district and community?

Now in its seventh year, Lizzy says they’ve helped many districts around the state and completed many projects and initiatives to ensure success for students in all areas.

To Lizzy, education is like an umbrella – something that covers you and keeps you protected. Safety and security should always be at the top of the umbrella. That doesn’t just mean locked doors or fire drills. She believes students should feel safe and secure. Also, they should have access to emotional learning and be socially trained on being in the world and how to treat others and “all of those things that are important.”

Underneath that, Lizzy says the other two important things are student outcomes and teacher effectiveness; student outcomes being not just academic, but soft skills that can be measured based on their engagement, programs and certification classes and more. Teacher effectiveness is important because if teachers feel effective in the classroom, they will stay longer and their retention rate is higher.

“All of those things, in my opinion, are what we should be striving for as a student experience,” Lizzy said.

Working Outside the Box

Aside from the consulting and advocacy work Lizzy does within her company, she also works with other projects as a volunteer. When she engages in school districts, she is paid to do a project, but a lot of trust is built. She is able to be a sounding board for leaders within that district or school board members.

“This is a unique time in Texas public education. We’re having to stand up and use our teacher voices and be strong advocates for kids,” Lizzy explained. “Sometimes, behind the scenes, I am able to coach and support community members who want to be more engaged and do the right thing for students.

“I also engage when it’s session time in Austin. I’m not afraid to talk to any lawmaker, to be open and honest. When I was working for the state, it was a little more difficult. But, you know, I’m in a great spot right now where I can say, well, pretty much whatever I want to say. It’s nice.”

The One Thing

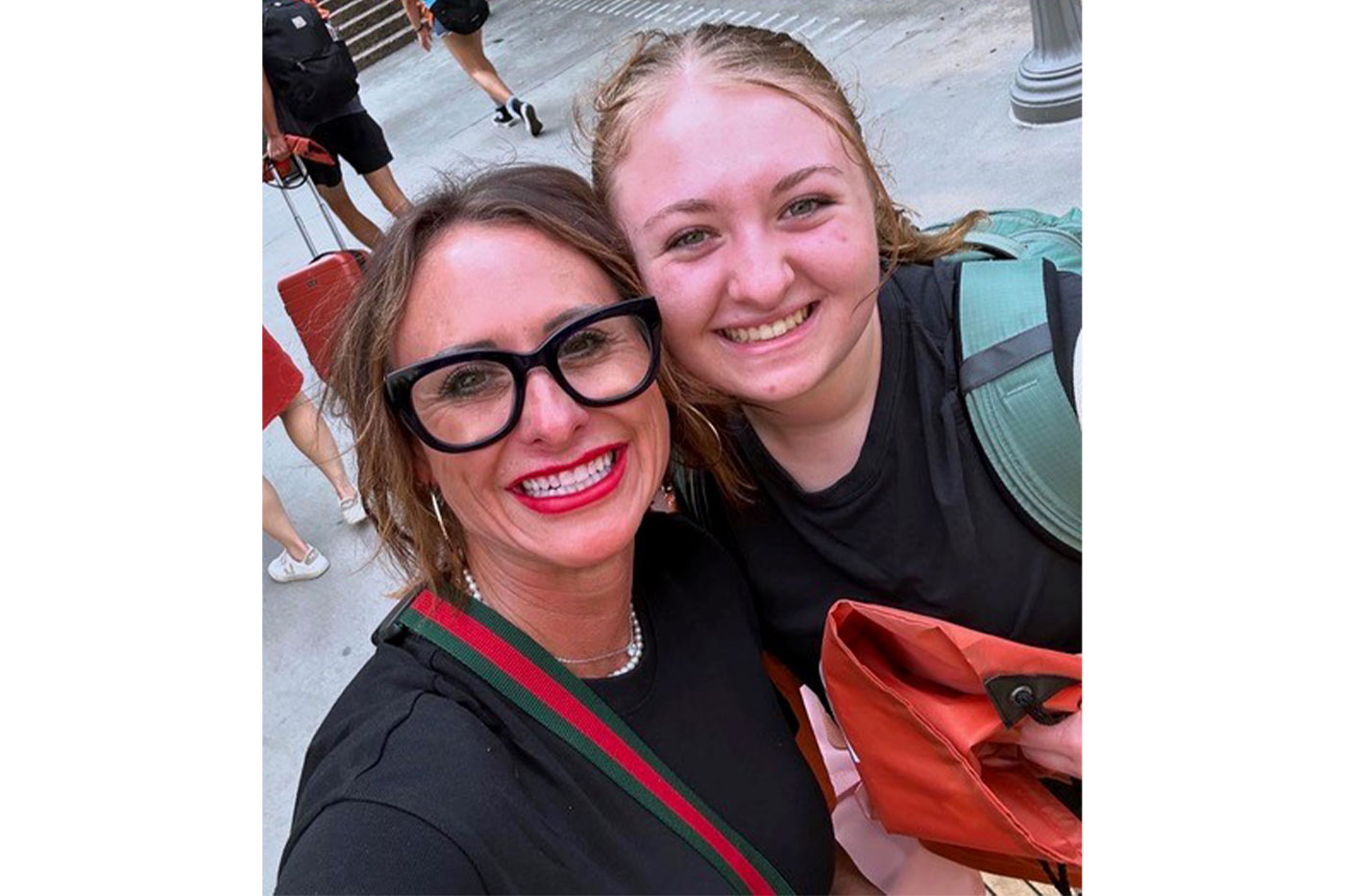

Lizzy believes a person can be good at a lot of things, but there should be one thing they really want to do well – one thing to be most proud of. She closes every presentation with the thing she’s most proud of in her entire life: her daughter Kloe.

“Out of everything I’ve done, I have raised this incredible human who is empathetic. She’s kind. She’s driven. She doesn’t take anybody’s nonsense,” Lizzy said with a wide grin. “She is just such a good person, and I want people to know I think you should always have one thing that you really want to do well in life. And when Kloe was born, I knew she was it.”

Much of Lizzy’s life has revolved around being Kloe’s parent and being her advocate as well.

Advocating for Education

Kallie Covington, the Celina high schooler-turned-Texas Tech doctoral student Lizzy mentored over the years, is now the associate director of development for the Office of Advancement in Texas Tech’s College of Education. Her main job is to raise not only funds, but other support for the college, its mission and its students.

She wouldn’t have made it there without support and inspiration from Lizzy.

When Kallie came aboard, her first real goal – outside of bringing in funds to the college – was the dean’s desire to create an advisory and advocacy council, a group of alumni from all facets of education to come together to see what the college was doing well and where it could improve.

“I went to the drawing board and thought, ‘Who’s really engaged with us? Who are rock stars in education? Who would like to serve?’ Lizzy immediately came to mind,” Kallie said. “It comes down to who’s really passionate about education, who’s passionate about being a Red Raider and who wants to give back. Lizzy fit those three boxes.”

With Lizzy’s connections across the state, she has been able to help the college by introducing superintendents and school districts to the College of Education, promoting its value and commitment to bettering the teaching and education equation in Texas and beyond.

Kallie says Lizzy has always been a big advocate for the college and for Texas Tech. But when asked what Lizzy’s biggest motivation is, Kallie didn’t miss a beat.

“She wants to help kids.”

Lizzy comes back to the fact that so many students and families don’t know what advocacy looks like or how it works. Parents are striving just to keep the lights on, the roof over their heads and food on the table. So, what better people to advocate for students than educators because kids are in that space day in and day out.

When Lizzy does leadership training, she asks incoming principals to imagine that everybody walks into their school with a backpack. Even the teachers, the cafeteria staff, the janitors, the bus drivers – everybody’s got a backpack. And everybody’s got something different in that backpack. It’s things they carry around with them daily and that sometimes they never release. They carry it their whole life. And sometimes the contents of the backpack change.

“You have to realize that everybody’s coming to your building with those items. You have to be aware of that,” Lizzy contemplated. “You have to be able to advocate for them – all of them – in that space, and not just about academics, but all the different items and ideas others carry in their backpacks, too.

“That’s why I would say my purpose, until I take my last breath, is going to be advocating for Texas public education.”