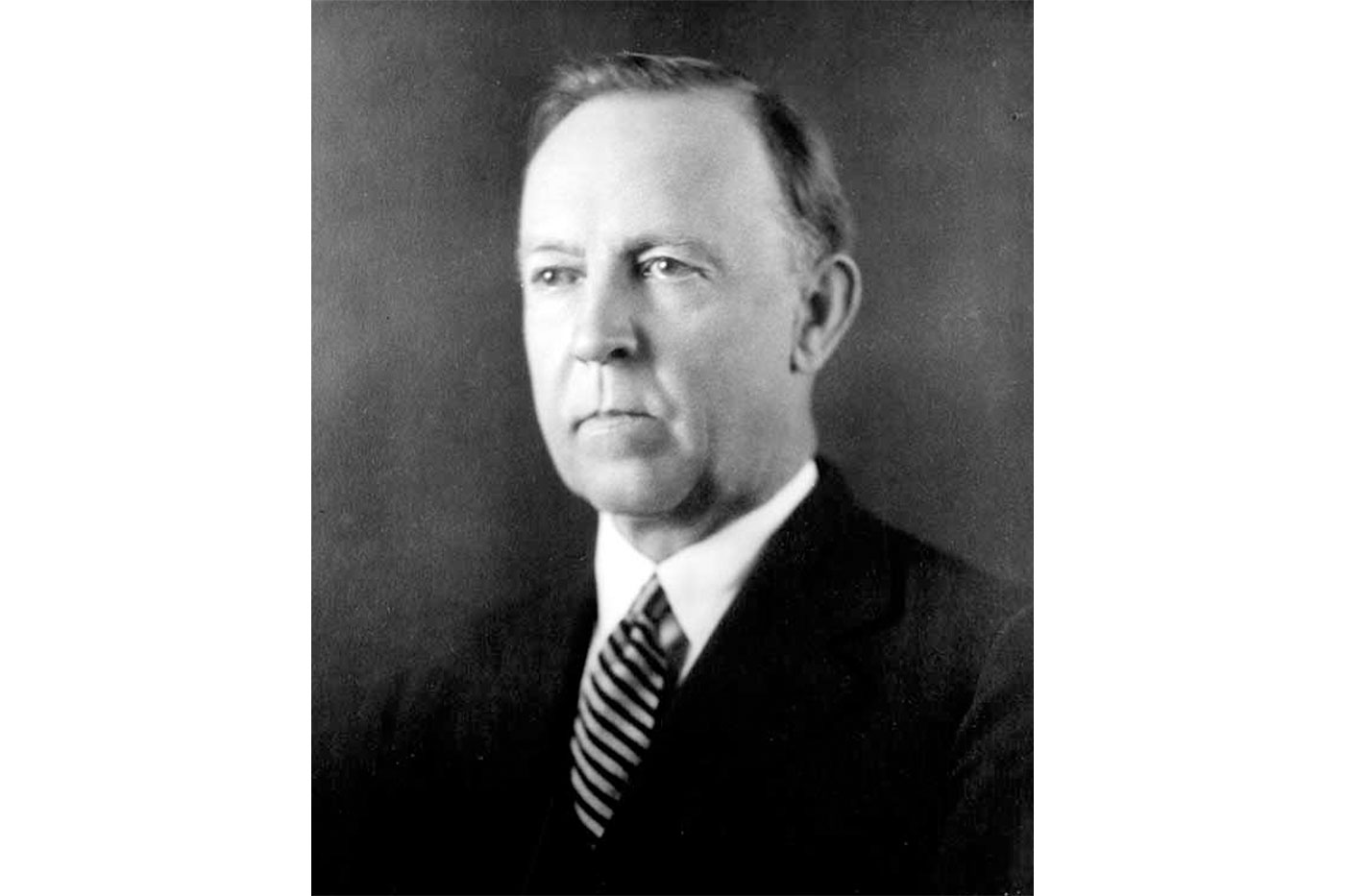

Much of the identity we now hold dear is attributable to the university’s first president.

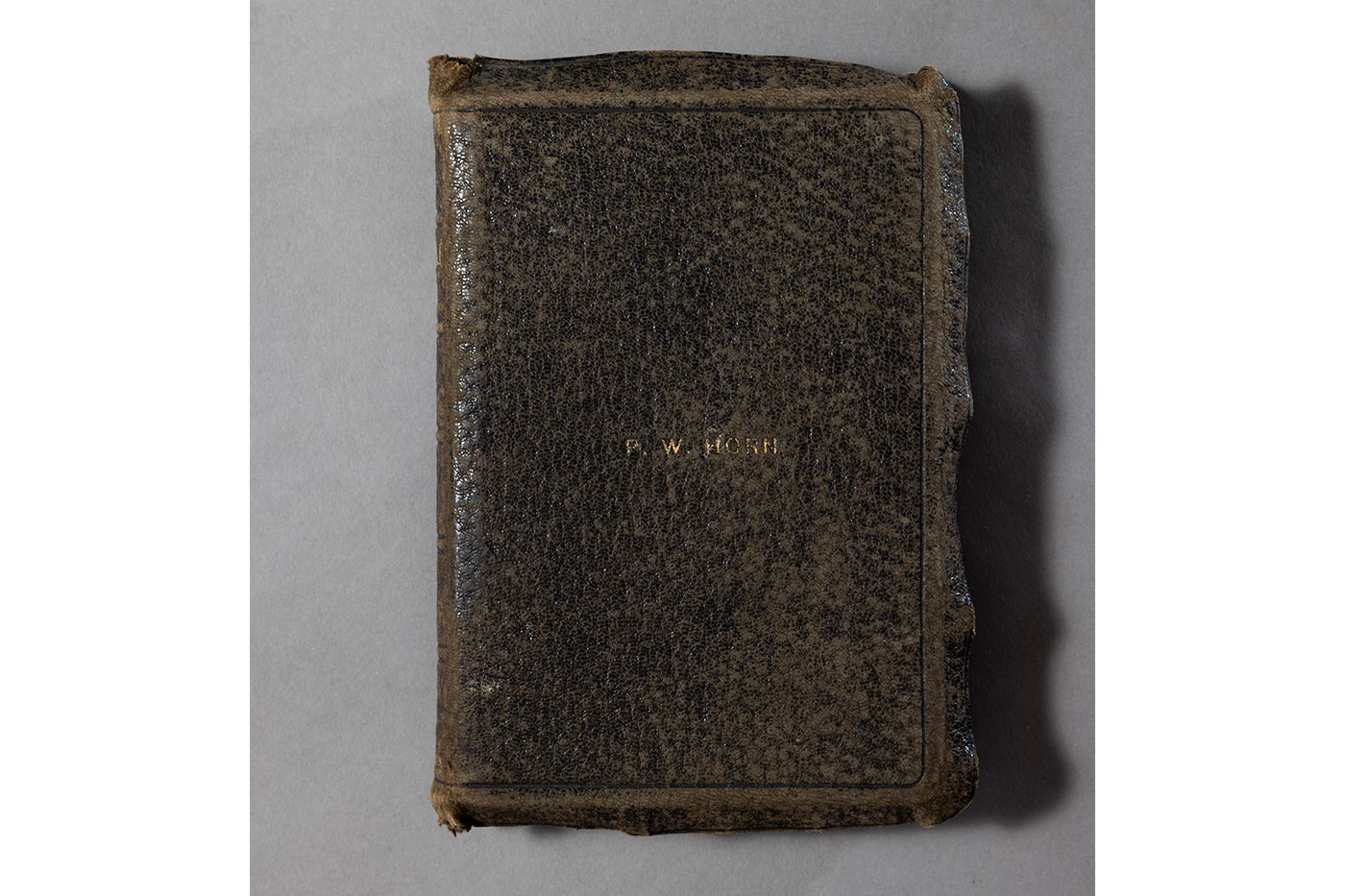

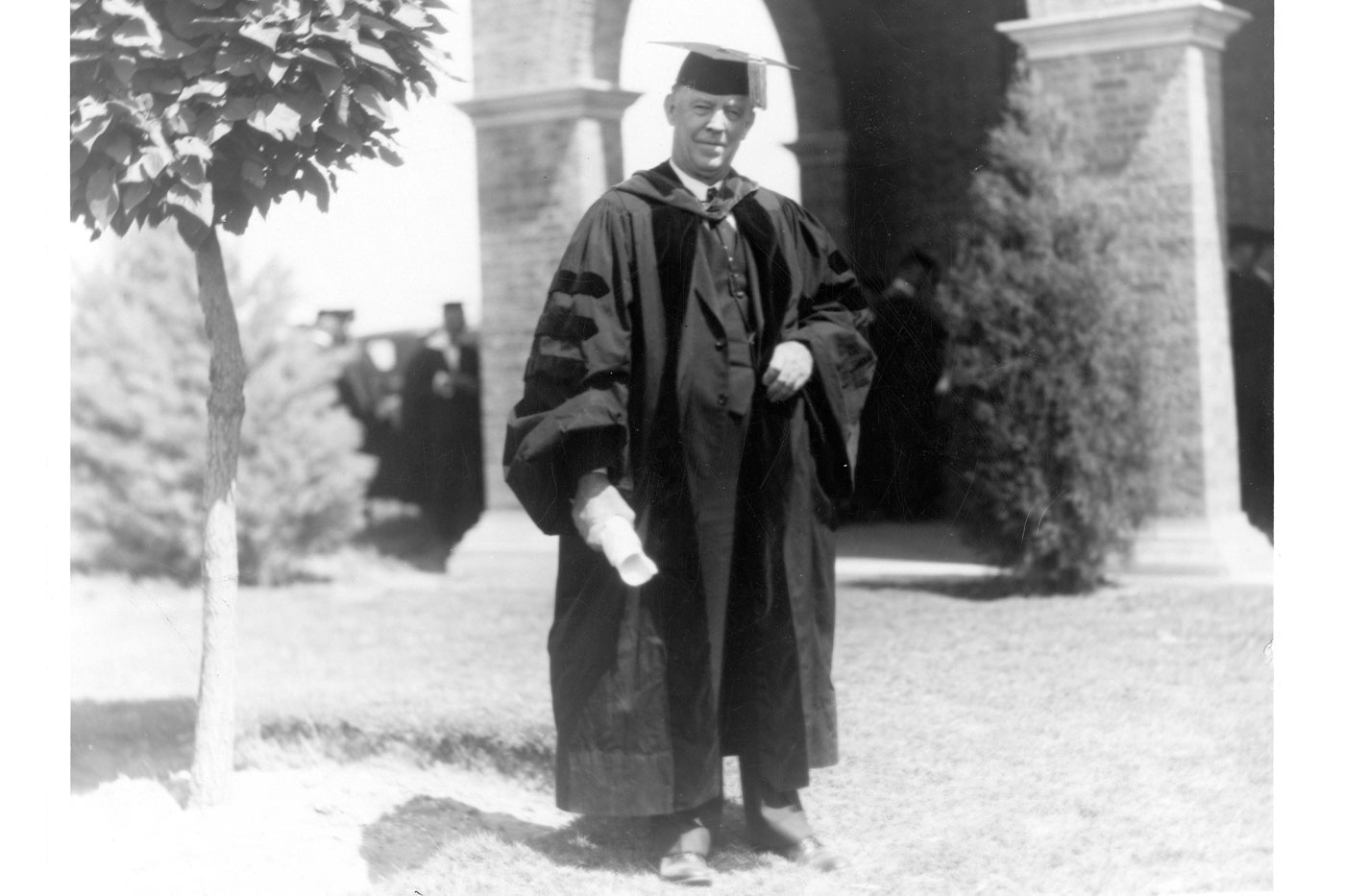

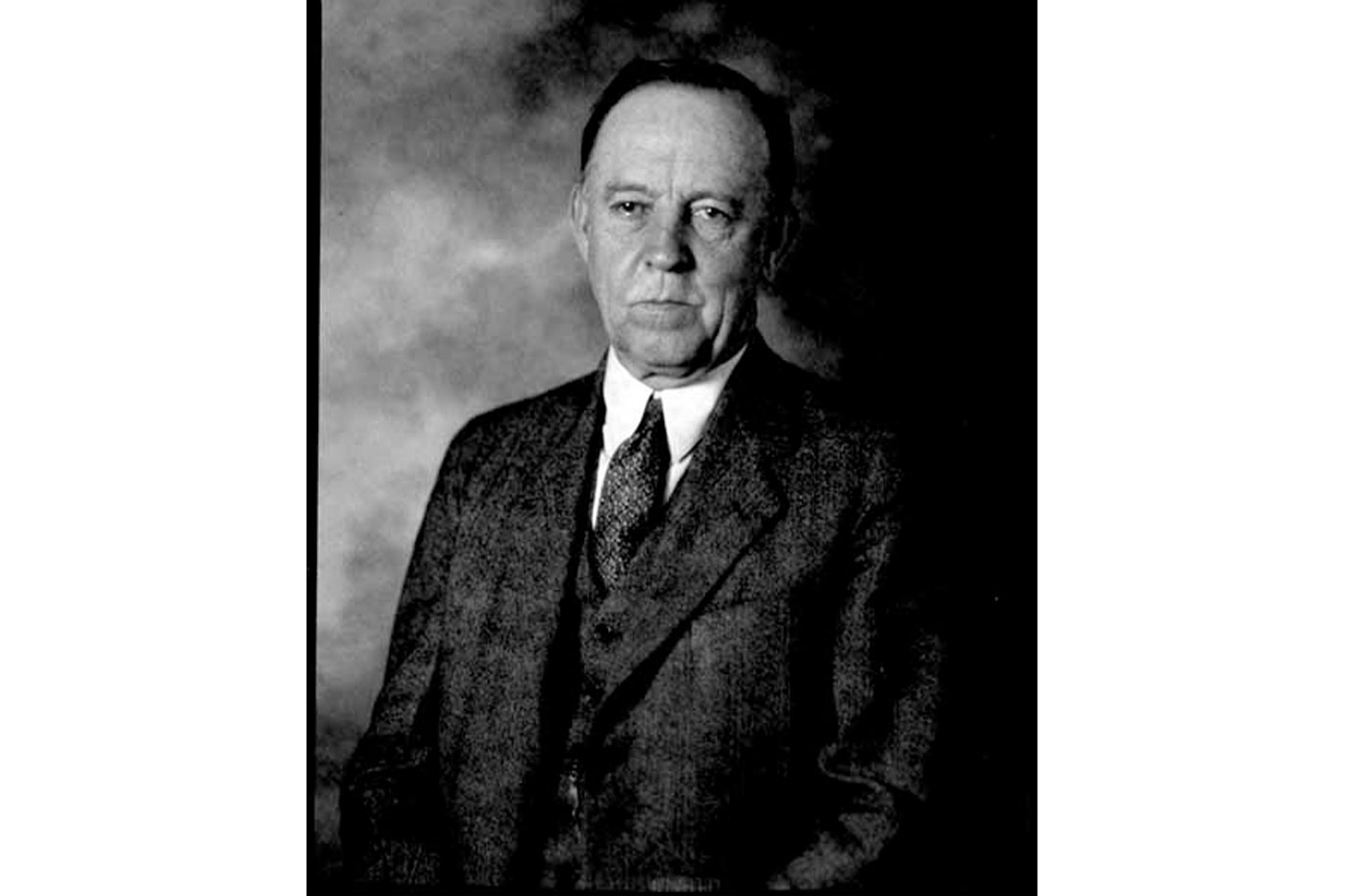

Today, most Red Raiders know the name Paul Whitfield Horn. It’s on a campus residence hall. It’s a scholarship for graduate students. It’s the highest honor our university can bestow on a professor.

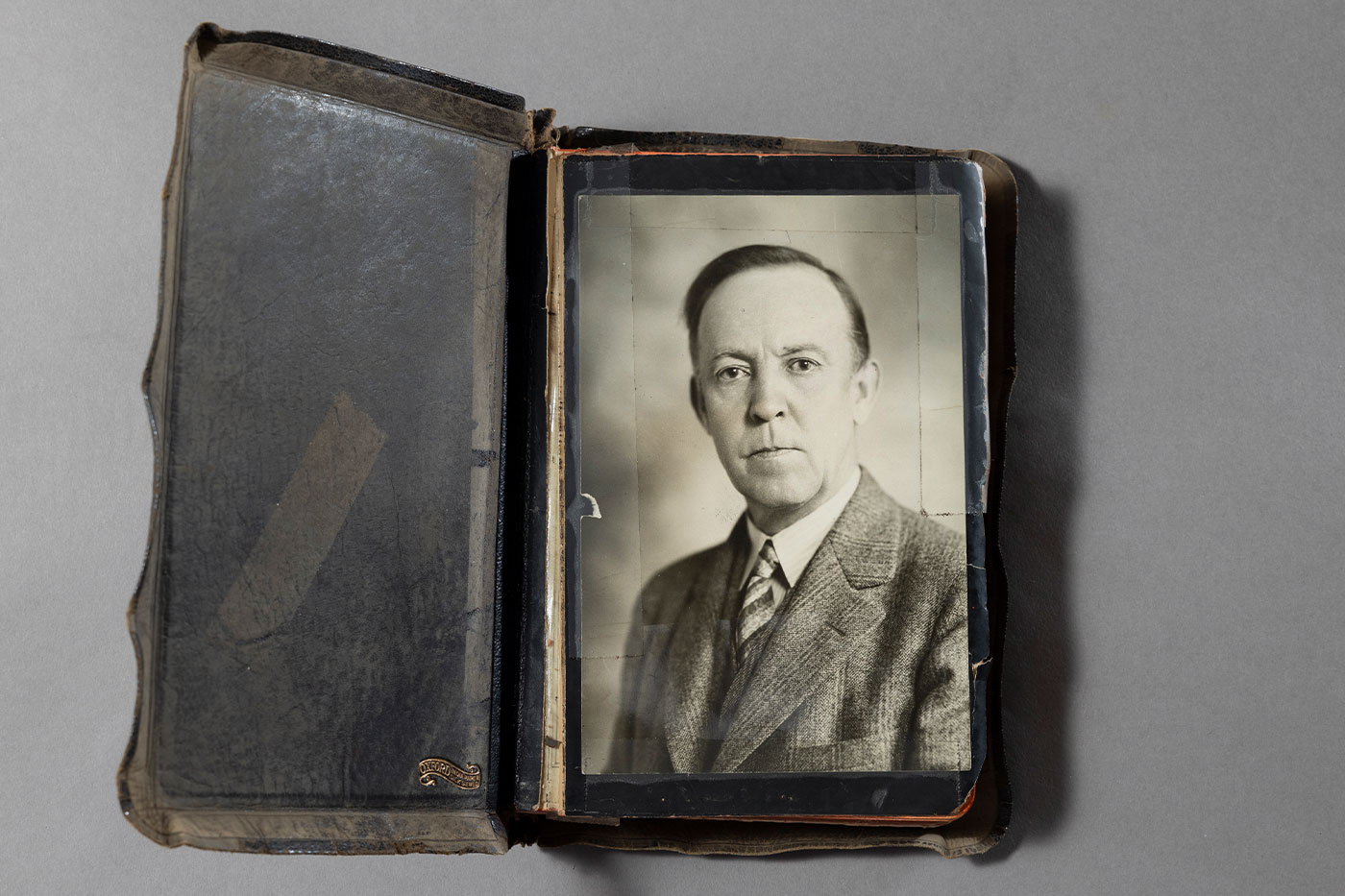

But behind that name was a living, breathing person.

You may not know much about Paul Horn, but it’s because of him – because of the ways in which he lived his life and impacted the lives around him – that we remember his name a century later.

This weekend, Horn’s legacy will be celebrated with the dedication of his long-overdue Texas Historical Marker at the City of Lubbock Cemetery. In commemoration, we bring you the story of the man behind that legacy.

Prologue

Paul Horn was born April 30, 1870. His father, George Washington Horn, was a Methodist preacher who had traveled all over Missouri before marrying Mattie Myers in 1869. They settled in her hometown, Boonville, to start their family.

The Rev. Horn became well known locally for his sermons, which were delivered with uncommon force and animation, but his fame also extended beyond the Missouri state line. Regarded as a “most captivating writer,” Horn published his sermons and articles in Methodist journals and publications throughout the U.S. and Europe. He was distinguished by his knowledge of the scriptures and, moreover, his beautiful use of language.

But behind the pen was a man suffering. He had tuberculosis, and although he traveled far and wide seeking treatments, it was killing him.

“I have now but a little time to wait,” he told a friend, “and sometimes on closing my eyes at night, I wish I might wake up in glory; not that I am impatient, but long to be at rest and to realize a life without pain and weakness.”

On Aug. 17, 1884, he succumbed to the disease. He was 45 years old.

Paul, the oldest of his three children, was only 14.

Chapter 1: An Education

Of course, Paul Horn was no ordinary 14-year-old. Whether it was because of his father’s influence or through some intrinsic quality of his own, Horn matured quickly and excelled in his education. Family legend recorded that he read the entire New Testament by age 4, and a scrapbook he started at age 8 held his own original writings. The same year the elder Horn died, the younger graduated from Boonville High School.

Come the fall, he packed his trunk and moved 10 miles away to attend Central College in Fayette, Missouri. It was a small institution with no athletics; instead, it offered robust literary and debating societies, as well as leisure for reading and thinking. It was a perfect fit for Horn, who preferred a slower pace. As his daughter later recalled, “Perhaps it was in freshman days that he acquired a distaste for the excessively busy man. The person who has so much to do that he never has time to do anything is regarded by my father with suspicion.”

And yet, after a year at Central College, Horn left school and got a job. He spent four months as a teacher at a county school, where he made $20 per month. We don’t know why he left college, but we do know at the end of that term, he returned to pursue his master’s degree, which he earned at age 18. And more importantly, we know the experience, and its lessons, stayed with him. Decades later, Horn would ardently defend the first year of college as the most important to a student’s success.

Horn had a future career in education just waiting for him, but after earning his master’s degree, he went into the newspaper industry instead – at least temporarily. This young man who’d been writing since childhood now had the opportunity to write professionally, a fact that seems to have made quite a difference later in his career. And yet, within short order, he returned to the classroom.

He moved to Jasper, Tennessee, for a faculty position at the Pryor Institute. There, he met Maud Keith, an elementary school teacher who became Mrs. Paul Horn in August 1890. Two years later, with their daughter Ruth in tow, the Horns followed his career to Texas.

Chapter 2: Finding a Niche

Over the next decade came a rapid succession of school after school, position after position. One year as principal at Valley View. Two as superintendent at Belcherville. Two as principal of Sherman High School and then seven as Sherman’s superintendent. In 1904, he took over as superintendent of Houston’s schools. As a going-away present, the teachers in Sherman presented Horn with a library table and a leather easy chair.

With the gift, teacher Mary Crutchfield told Horn of his impact on their community:

“This influence of yours has been wider than you ever dreamed,” the Sherman Daily Register quoted her. “It is felt in the church, in the school and in the home. I passed a group of little boys of perhaps 10 years of age the other day and they were discussing not a game of ball or fishing, but the departing superintendent. The name of Mr. Horn has long been a household word in Sherman.”

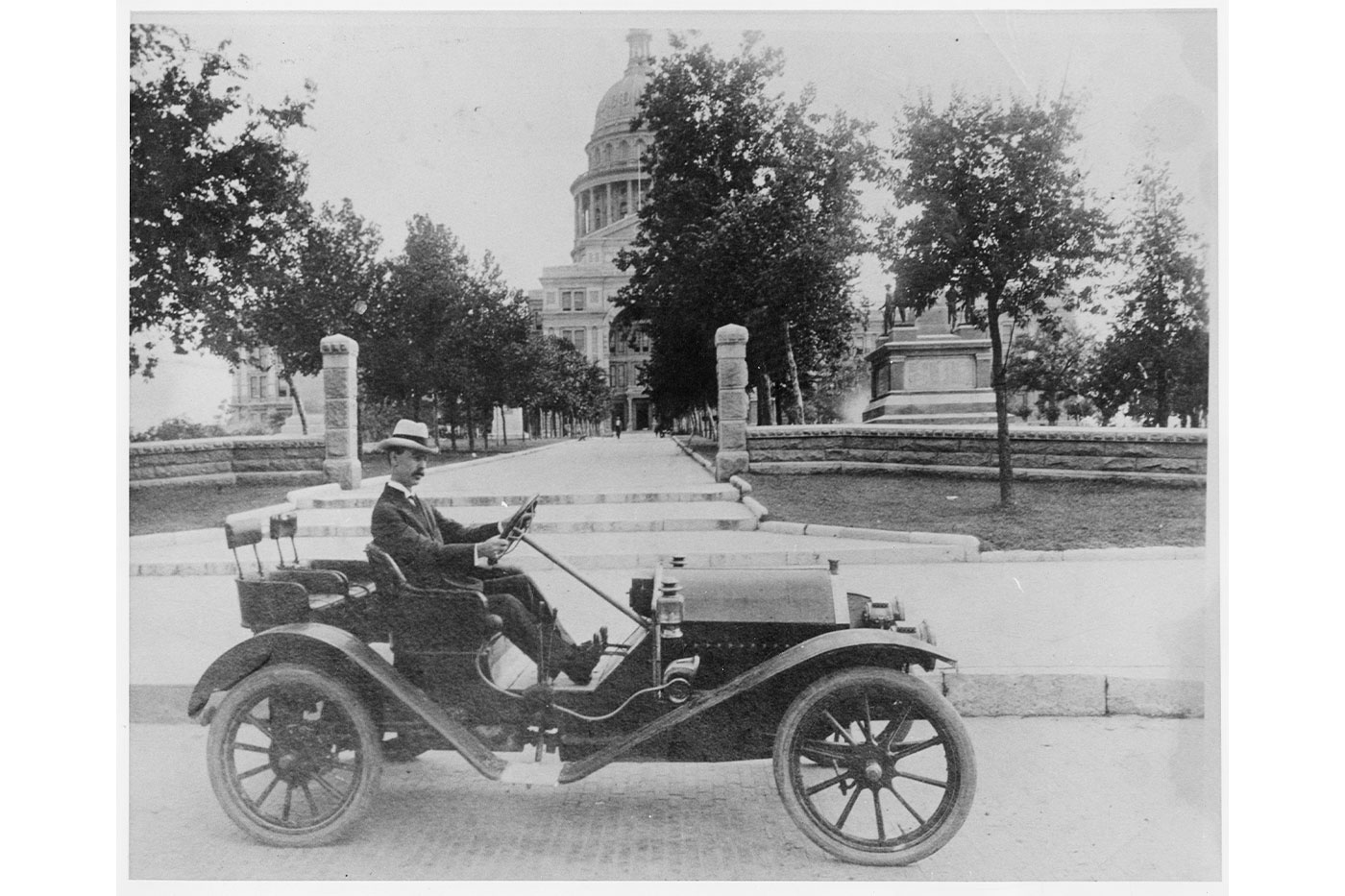

It seems that Horn made an even greater impact in Houston than Sherman. Over the next 17 years, he transformed the city’s public school system. He introduced a junior high school plan, for which the district received national recognition. He also implemented plans to make education more accessible and applicable to a wider student body: Hands-on training. Free kindergarten. Special classrooms for deaf and mute children, with teachers specifically trained to meet their needs. Night school, which eventually became affiliated with the bureau of naturalization to prepare immigrants for U.S. citizenship.

It’s an understatement to say Horn’s approach was ahead of its time. But perhaps what made him so exceptional was simply that he actually lived up to the lofty ideals he espoused. In his 1908 book, “Our Schools Today,” Horn wrote that service to others is what sets such men apart from their peers.

“No man is great unless he has done some great and useful work in the world,” he wrote. “The greatest is simply the man who has helped the most.”

By that definition, Horn was certainly a contender. You see, while doing all that in Houston, he also served as president of the Texas State Teachers Association and vice president of the National Education Association. He helped survey schools in Oregon, Texas, Oklahoma and Alabama to see how they could better serve their students.

In 1916, the citizens of Houston threw a banquet to celebrate Horn’s (at that point) 12 years there. The Rotary Club held a special meeting in his honor, where he was recognized as the greatest civic force in the city. And yet, the honor that meant the most to Horn was a magnificent silverware set given by the Black teachers from Houston’s public schools.

Houston’s schools were still four decades shy of racial integration efforts beginning. Across the country, many district administrators of the time either ignored or actively worked against the Black campuses under their control. Not Horn. An accompanying letter thanked him for his “abiding interest” in the Black schools and “broad and painstaking spirit” that had elevated them among the best in the nation. It was signed by all 135 members of the Negro Teaching Force of the Houston Schools.

Horn’s efforts in education earned him honorary doctorates from Baylor University, Southwestern University and Central College the following year. But even then, he was just getting started.

In 1921, he was invited to become superintendent of the American School Foundation in Mexico City, an opportunity Ruth later said captured his imagination. One year in Mexico, however, was enough, and Horn was ready in 1922 when Southwestern offered him the chance to become a university president. Arriving in time for the university’s 50th anniversary celebration, he found there a well-established institution he could see himself contributing to.

He’d been there for an entire academic year by the time of his official inauguration in June 1923, as part of the Golden Jubilee. In his inaugural address, he described his conception of education for the purpose of human service. Rather than promoting pure scholarship for its own sake, he envisioned a democracy-based program that would teach students to become good citizens with ethical habits. He seemed intent on building such a program there at Southwestern.

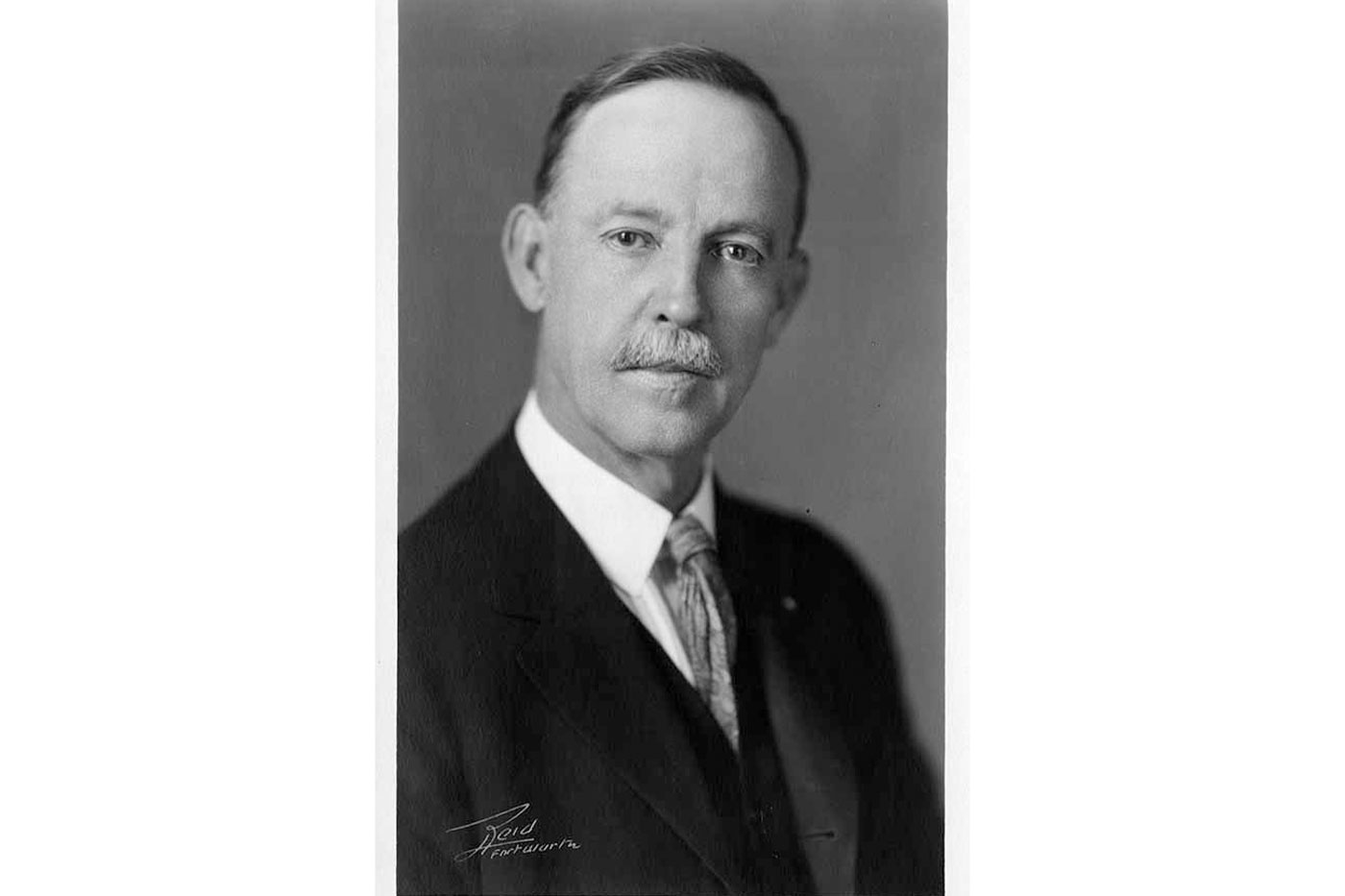

But only five months later, an opportunity arose that Horn simply couldn’t turn down. On Nov. 22, 1923, he was selected as the first president of the newly founded Texas Technological College, a position that elevated him to prominence beyond the field of education.

As a newspaper editorial soon pointed out, the college’s progress was being followed closely, not only within higher education and among teacher associations but also by all the industries related to the creation of a new school – like architects, construction firms and companies that produce chairs, desks and school supplies – and among all kinds of people that could possibly be employed at the college, from the most educated administrators to the humblest staff members.

That put Texas Tech on the map and brought visibility to the person leading it. Rather than refocusing Southwestern’s existing programs, the Texas Tech position offered Horn the ability to shape an entire institution’s direction from the ground up: selecting its faculty, dictating its focus, designing its facilities, creating its traditions and more – in the national spotlight. Perhaps it could lead more institutions to adopt Horn’s strategy for education.

So, Paul Horn set forth to lay the foundation for what Texas Tech is today.

Chapter 3: The Groundwork

Whether a byproduct of his years leading a classroom or his years as a writer, one of Horn’s greatest strengths was his ability to communicate and, especially, his penchant for memorable quotes.

In one of his first interviews in his new role, nearly two years before the college opened its doors, he joked to the Fort Worth Record-Telegram, “Other college presidents envy me because Texas Tech has never been defeated in football and no member of the faculty has ever been accused of saying a foolish thing.”

He was also a visionary who perpetually painted for others his portrait of Texas Tech’s legacy.

“It is my intention to build for the future of Texas Tech – 50 years of the future, so that the college will become one of the largest and best in the country,” he said.

“The word that will stand out in the school is ‘service.’ The school will not be an infant 30 years hence as it is today and I don’t hope to not make any mistakes. But I pledge the people of Texas that Texas Tech won’t turn its face from human service. We will absorb the glories of the past, but ever keep our faces to the future.”

And, just as in the Houston public schools, Horn wanted to make education as accessible as possible.

“My ambition for this school is that no man shall be so rich that he can buy anywhere a better education than we can give him,” he said, “and that no man or woman will be so poor as not to be able to take advantage of the education it will offer.”

To that end, within his first three months, Horn undertook an extended tour of the U.S. to better understand how other technical colleges operated. By mid-March 1924, he presented to the Fort Worth Rotary Club how Texas Technological College would be organized. Four branches, he explained, would coexist: liberal arts; a department for women focusing on home economics and homemaking; agriculture; and engineering, including textile courses.

And indeed, Horn’s vision for the college was soon being lauded nationally for its uncommonly common-sense approach. His 20-point “Horn Heresies,” published in October 1924, included several points sure to make some in higher education squirm:

- Faculty members should set a high value upon scholarship, a higher value upon human ability and a still higher value upon human character.

- They should see that the failure of a freshman is just as much a tragedy as the failure of a senior.

- A college that boasts that one-third of its freshmen fail is no more sensible and humane than a doctor who boasts that one-third of his patients die.

- The democratic college tries to help folks in; the aristocratic college tries to keep folks out.

- The moment standards of admission are used for the purpose of excluding from college those who might otherwise enter and profit from the work therein, they become instruments of the merest intellectual snobbery.

But these were more than just glib taglines. Beneath them lay a depth of experience in education and a legitimate concern for what Horn did not want to see the college evolve into. In December 1924, just weeks after the Administration building’s cornerstone was laid before a crowd of 20,000 people, he published the first Bulletin of Texas Technological College. Titled “Foreword: The College That Is To Be,” it walked readers point by point through his thought processes on selecting people of good character to teach and train students, what the institution’s philosophy should be, what subjects should be taught, what the physical spaces should do and be, and what kind of students the college should attract.

Chief among his thoughts were two points: that a college can be a powerful agency for good in shaping individual men and women’s lives and in building up a true democracy, but also that some colleges may be – and actually are – factors for evil.

For that reason, Horn desired faculty members “above pettiness, strife and jealousy” – those who could get along with people while being capable teachers, enthusiastic about their subject and sufficiently prepared for the task at hand.

“President P.W. Horn of the new Texas Technological School at Lubbock, the cornerstone of whose first building was recently laid, is likely to make Texas famous in college life,” the Journal of Education read that same month. “At Lubbock President Horn has an unprecedented opportunity, and in West Texas he has a pioneer spirit that welcomes the educational Rough Rider. There are no moth-eaten traditions, no anemic scholastic aristocracies in West Texas.

“If President Horn can survive the scorn of the scholastic aristocrats, he will be one of the educational wonders of the times. Whether he is wise or otherwise in his heroic announcements President Horn is no educational Bolshevist, no escaped lunatic, but a man of superabounding common sense, as well as a man of fearless courage. Everyone will watch Horn of Lubbock.”

Chapter 4: Building for the Future

Of course, Horn wanted to ensure his vision for the college would be more lasting than the paper his Heresies were printed on, so he recorded them in stone. He personally worked with architects William Ward Watkin and Wyatt Hedrick to design the early facilities of the Texas Tech campus, including the Administration building.

On its façades can be found the names of notable individuals from American and Texas history as well as the names of people whose endeavors made great impacts upon humanity; the seven subjects the college was designed to teach – Agriculture, Science, Manufacturing, Democracy, Home Making, Art and Literature; and more.

Horn’s focus on democratic values ran deep. He even included a statement from Mirabeau B. Lamar on the Administration building: “Cultivated mind is the guardian genius of democracy. It is the only dictator that freemen acknowledge, the only security freemen desire.” In putting that belief into action, Horn barred fraternities and sororities from campus because, to him, their very existence created artificial class distinctions, flying in the face of the kind of inclusive, values-based college he was working toward.

“Democracy shall be established in every department and activity of the new college,” Horn told the Fort Worth Star-Telegram in September 1925. “Generosity will be given emphasis in dealing with all students throughout the initial term, and throughout the life of the institution.”

As Texas Technological College opened its doors in October and set to work educating students, pieces of the campus experience immediately bolstered Horn’s all-for-one, one-for-all vision.

In establishing the college, the Texas Legislature had given it enough money to get started, but not much more. Thankfully, Lubbockites and Texas Tech community members were determined to make it work, and that showed up in numerous ways. For instance, the college didn’t have any residence halls constructed when it opened, so Horn appealed to Lubbock residents to open their homes to students, and they did. Also, the campus library was insufficiently stocked for the hundreds of students who needed to use it. To bridge the gap, faculty members lent students books from their personal collections until the situation could be rectified.

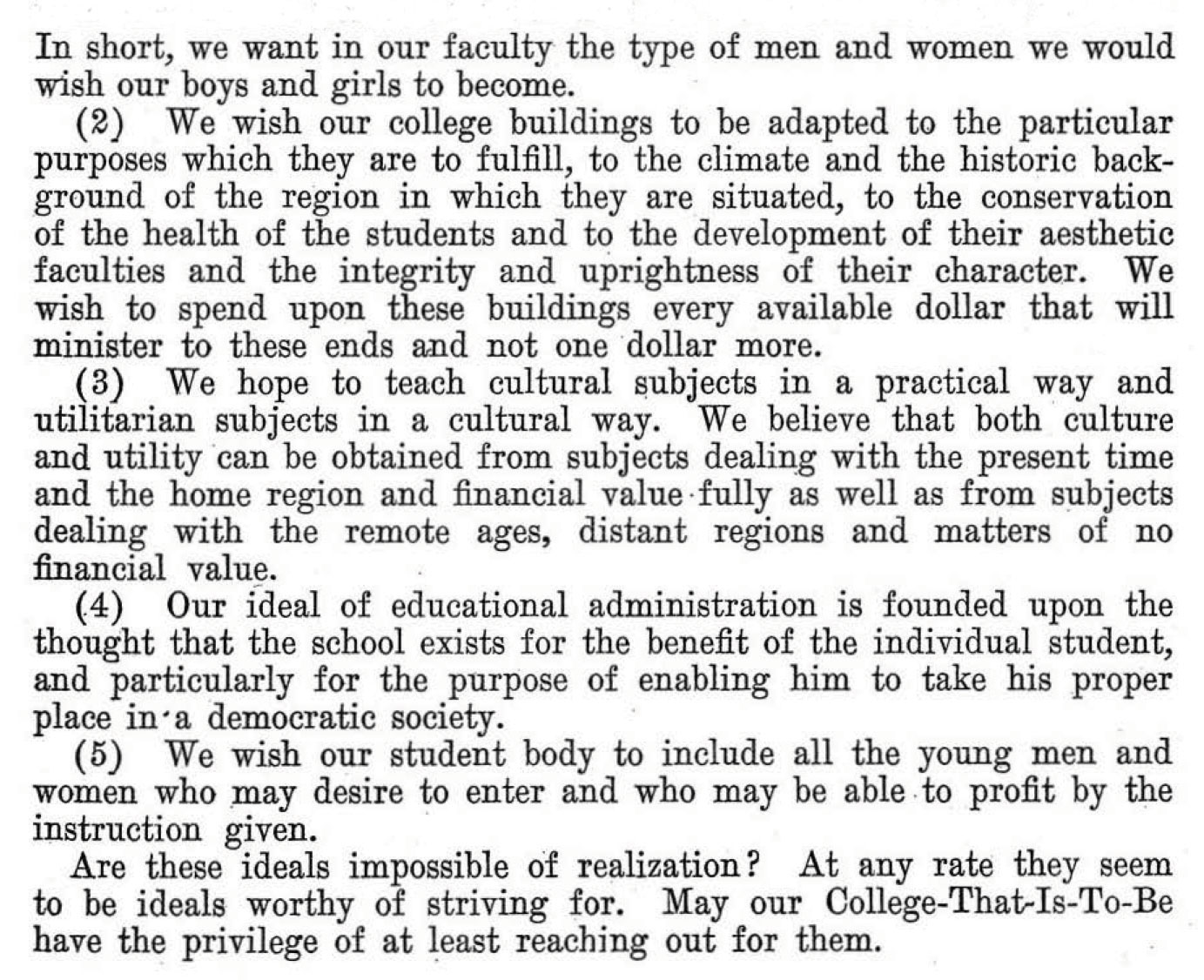

Indeed, it became immediately apparent that the faculty who’d signed on, as well as the 910 students who enrolled, had bought into Horn’s dream for Texas Technological College and were committed to making it a reality.

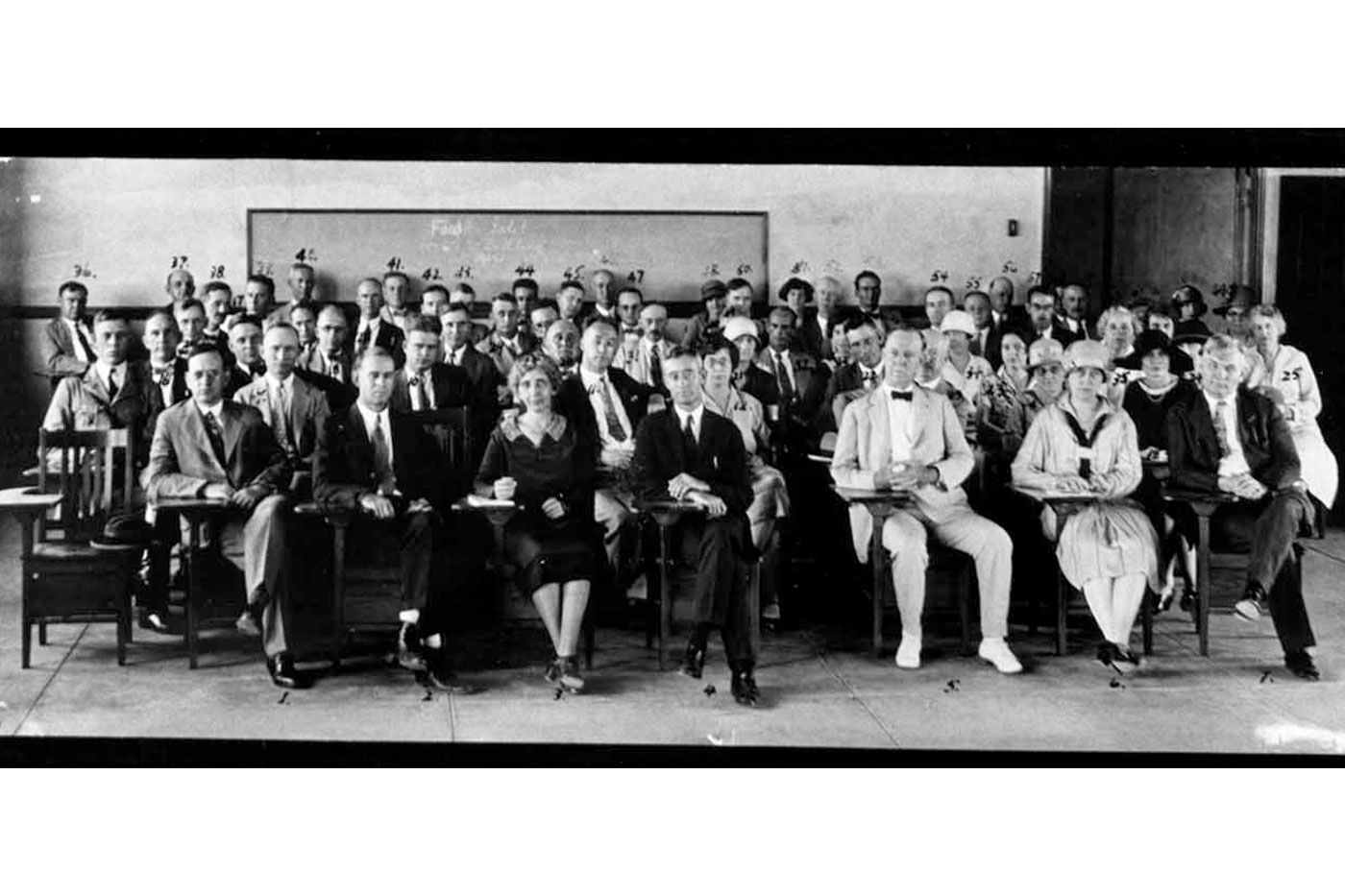

Horn wrote a letter to campus that appeared in the very first campus yearbook. One paragraph from that message has become exceptionally well known over the first 100 years of Texas Tech’s life, because it encourages us to perpetually think bigger, but the whole writing is even more impactful.

Chapter 5: Doing Good Work

By the beginning of the college’s second academic year, Horn was being lauded publicly for what he’d accomplished. As a Lubbock newspaper editorial prevailed upon its audience, “Think back over the record of Doctor Horn. He came to Lubbock when there was nothing to Texas Tech except a bare field. He took nothing plus plans and from them builded a great institution, drawing upon his experience, his brain, his ingenuity and, in many cases, his physical energy to make Texas Tech what it is today.

“Of course, that is what the board of control expected when it chose Paul Whitfield Horn as the college’s president. The regents thought he could carry the burden and solve the problems or he never would have been selected for the task. Yet a job well done is one for which praise should be given and the Journal herewith pauses from the hustle and bustle of everyday life to call the attention of the general public to the man behind the gun at Texas Tech.”

By the 1929-30 academic year, the college’s enrollment had topped 2,000, including international students from China, Korea, Mexico and Guatemala. It had truly become the institution of worldwide terms Horn envisioned.

“The Texas Technological College is still a young institution, as colleges go, but nevertheless, it is beginning to accumulate quite a family of students and former students,” he wrote. “We have been in existence only five years and have had only four classes graduating. Nevertheless, these graduates and other former students are beginning to have their effect upon things. We find them teaching in the public schools and colleges, supervising farms, taking their part in the industries, and in general, doing their share of the work of the world.

“In the last analysis, these graduates and former students are the final evidence as to the strength or the weakness of a college. Every time you find a college graduate who is doing a part of the world’s work and doing it better than most people, you find evidence of the fact that the college has done good work.”

Chapter 6: ‘Did I Do My Best?’

Like his father, Horn shared his perspectives with the world through published books and articles for most of his career. But as Texas Technological College became increasingly well established, his writings began to focus less on the institution and more on the individual.

Perhaps age was a factor in his introspection. Horn had turned 60 in 1930, two years past the average life expectancy for men at the time, and 15 years more than his father had lived. His faith, which had always been visible, now became a throughline in his writings.

In many, he seemed to be grappling with the idea of whether he’d done enough.

“Some men never in all their lives do the very best work of which they are capable,” he wrote in October 1931. “Some do their best on certain occasions. Others do their best all the time. These last are usually the ones who make the greatest success, both for this life and for the life to come.”

An article in November posed the question of duty, and to what extent each person does theirs. “What kind of a league would this league be,” he asked, “if every member were just like me?”

In December, he encouraged his readers to examine themselves: “The great question is not as to whether I did better or worse than some other student,” he wrote. “The important question is, ‘Did I do my best?’”

It seems his self-reflection was just in time.

On a Sunday afternoon in January 1932, Horn began feeling ill. His symptoms worsened overnight to the point that, come Monday morning, he went to the hospital. He was immediately diagnosed with appendicitis and rushed into surgery to have his appendix removed.

By mid-March, he was back in the hospital with kidney problems. Released four weeks later, he returned home on Monday, April 11. He spent Tuesday entertaining friends and college officials at the President’s Home on campus.

On Wednesday, April 13, he collapsed after his morning bath and suffered a heart attack. He was gone before his doctor arrived.

Chapter 7: ‘The Lingering Glance’

Condolences and memorials immediately poured in from across the country.

That very night, the Lubbock Evening Journal published, “As mere words falter in expressing wide-spread grief attending Doctor Horn’s passing, suffice it to say that no doubt clouds the glorious reward to which he has gone – a reward earned through more than three-score years of his life among men. The age-old cry of ‘God, Give Us Men!’ was answered in the mortal career of Paul Whitfield Horn. Man’s only return today can be ‘Thy Will Be Done!’”

The Dallas News remembered, “His outlook on life and citizenship was sensible, wholesome and refreshing. He adapted himself to the manners and pace of West Texas admirably, understanding the caliber of the people and the heartiness of their hearts. He became one of them and served their needs the better for it. It is especially unfortunate that West Texas Tech loses its guiding intelligence so early in its formative period. It is of the highest importance that the policies that have won such approval for their soundness and foresight shall be carried out in the spirit of the man now dead.”

Oklahoma’s Daily Ardmoreite recalled his legacy: “When the schools of Indian Territory, a generation ago, needed reorganization and rejuvenation, it was Dr. P.W. Horn of Texas who was sent here by the federal government to do that work. When English education in the City of Mexico stood in need of having its weak points strengthened it was Dr. Horn who was called to that important work. When Georgetown University needed a president Dr. Horn was called and responded to the demands of that institution of learning. When the great state of Texas reached the conclusion that it was ready for a technological school Dr. Horn was again called. He went to Georgia Tech and to Boston Tech and other similar institutions to learn of the building problems and he stood beside the architect as he directed the construction of the buildings. He opened the first classes. He was the inspiration of that institution from the date of its founding until last week when he passed away in his home while still serving as president. As long as there is a Texas Tech the name and the works of Dr. Horn will be known and revered.”

And, for its part, the campus newspaper invoked his name in calling for the continuation of his work: “Texas Technological College will carry on because it has instilled in its soul that ‘never dying’ spirit so vividly taught by its first president Paul Whitfield Horn. Tech will carry on because Dr. Horn would have it do so. As time goes on there will arise a man who will eventually take over the work of Dr. Horn. But the Toreador is of the opinion that to completely fill Dr. Horn’s place now is an impossible task. Texas Tech will move on to become even greater and become that exceedingly great institution that its first president visualized. It is His wish that we do so.”

Horn, after all, kept working, and writing, to the end. Even during his illness, he continued. When he was unable to put pen to paper himself, he dictated his thoughts to his daughter, Ruth. He was so far ahead of schedule in his weekly articles for The Adult Student that his last piece didn’t run until mid-November – more than 7 months after his passing.

A few months before his death, Ruth dutifully recorded for her father a piece he titled “The Lingering Glance.”

It is rather a handsome living room in which I sit for a while in the evening and read and sometimes study. At least it seems so to me.

When time for retiring comes, I switch off all the lights except one and then glance back at the room for a moment.

There are the chairs and the rug and the high mantel with the picture of the ship over it. There are the brass candlesticks containing the never-lighted tapers. There is the tall, shaded reading lamp standing by the big chair. There are also a few books and magazines.

There is the dark sheen of the grand piano, and the reflection of the white piece of marble above it. There is also the radio cabinet.

Sometimes there is a smouldering glow of the coals in the grate.

I like to glance back for a moment at the warmth and light and love that beautifies the room.

Then I switch off the last light and turn my steps upward on the stairs toward sleep and rest.

I think that when the time comes to leave familiar scenes for the last time, I shall do the same thing. When most of the lights are out, I shall glance backward with love and a tinge of regret for the grass and the flowers and many beautiful things. And especially for the light and warmth of love that has beautified the home.

After all, it has been a rather beautiful old world; and the best of us might at least have a touch of regret at leaving it.

But when the last light is out, I think I shall, with more or less of readiness, turn my back upon it with the hope of rest and sleep – and a new greeting of friends in the morning.

Epilogue

Today, not many Red Raiders know Paul Horn’s story, nor do most of us feel his absence as acutely as our predecessors. Perhaps that’s because we have the benefit of time. We can see how his vision unfolded over the course of the last century, and we know that what he dreamt has come to fruition.

Of course, his work will never truly be finished.

While Texas Tech is now far larger than the college Horn was familiar with, at its core, it is the same in many ways. The values he established – which the first faculty and students adopted – still distinguish Texas Tech from its peers.

“Every college that is worthwhile has an individuality of its own, just as every person who is worthwhile has a personality of his own,” Horn wrote. “No two good colleges are absolutely alike. No two of them ought to be.

“The Texas Technological College has not the slightest desire to be exactly like any other college in the world. It desires to be itself, and to render certain service better than does any other college.”

It’s what Horn described as “The Spirit of the Texas Technological College,” and in his honor, we continue to uphold it.