Devi Khajishvili researches Georgia’s tea history to better understand the country’s past and craft a post-Soviet Union identity.

For some, reading tea leaves is a practice of divination, interpreting patterns and shapes to predict the future or offer advice.

Devi Khajishvili, a doctoral candidate in the Department of History in the College of Arts & Sciences, researches tea to uncover a small portion of the Soviet-era past of Georgia and to help re-establish the country’s modern identity.

Devi was born in Georgia as the Soviet Union was dissolving in 1991. As a child, the influence of the Soviet Union hung in Georgia’s zeitgeist for years after the country gained its independence. Like echoes reverberating in the distance, the narrative intertwining the Soviet Union and Georgia would become harder to discern over time.

“I would always hear mixed stories about the Soviet Union, Stalin and Georgia,” Devi said. “When I got those mixed stories, I just wanted to know what actually happened.”

Devi has turned to history and his education to find answers. His dissertation examines Georgia’s tea production during the Soviet era. Already, he has started to uncover information that puts his home country in a whole new light.

“If Georgia had been an independent country during the Soviet period, it would have been the third largest tea producer in the whole world,” Devi said proudly.

Now, Georgia’s tea production is minimal with many former tea plantations and production sites abandoned or repurposed.

Devi’s research has garnered attention over the last two years.

In 2023, Devi was named a Fisher Fellow and conducted research at the Russian, Eastern European, and Eurasian Center at the University of Illinois. The award was funded through the U.S. Department of State, and Devi used this research as a preliminary step for his dissertation.

This past August, Devi received a prestigious Fulbright-Hays award, which funds one year of his research overseas in Georgia.

“I’m extremely proud of Devi Khajishvili for receiving the Fulbright-Hays Fellowship this year,” said Mark Sheridan, dean of the Graduate School. “It recognizes the importance of his research as well as the high quality of the history program at Texas Tech.”

Devi is the second history doctoral student to receive a Fulbright-Hays award; Mengesha Endalew received the award in 2023. Prior to this run of back-to-back recipients, the last time Texas Tech University had a Fulbright-Hays recipient was in 2004.

Alan Barenberg, associate professor of history and Devi’s adviser, could not have been more excited for and prouder of Devi.

“I’m just so thrilled,” he said. “On one level, it opens up huge opportunities for Devi to do the rich kind of research for his dissertation. On another level, the dissertation can be a long process, and there aren’t many positive things along the way to make you feel like you made the right decision or are making good progress. Winning this award is confirmation of Devi’s impressive abilities as a scholar.”

For Devi, the Fulbright-Hays award serves more than just recognizing his research and dissertation.

“This award is a big achievement for me, especially as a kid who struggled in school,” Devi said. “I never thought I’d get to the point of getting a Ph.D., let alone something like the Fulbright-Hays award.”

Becoming a Red Raider

Devi looks back at his childhood like many students might. There were good times and challenging times, but he never lacked the support of his family.

Devi’s father is a world-champion martial artist and president of the World Shotokan Karate-Do Federation in Georgia, and his mother is a piano teacher. From opposite crafts, Devi learned the value of discipline and a creative curiosity for the arts.

Devi, though Georgian, grew up speaking Russian because he was around his Russian-speaking grandparents for most of his childhood. When he started to take English classes in school at age 8, he turned to movies to help develop his language ability further.

Devi spent countless hours with his grandmother watching U.S.-produced movies like “A League of Their Own” and “Little Shop of Horrors” and writing down unfamiliar words to broaden his vocabulary.

“My grandma instilled this courage in me,” Devi said. “We would dream together watching movies. I vividly remember those moments and dreaming like, ‘God, will I ever go to the U.S.?’ It was such a distant thought and felt impossible to do.”

Devi credits Mark Webb, professor emeritus in the Department of Philosophy, and his wife, Virginia Downs, with bringing him to Texas Tech. The couple met Devi while in Georgia with the Institute of Interfaith Dialogue. At the time, Devi was entering his final year of high school. Mark and Virginia had been staying at hotels up to that point, but Devi insisted they stay with his family

“We got up for breakfast, and the table was groaning with food,” Mark said. “They decided to put on a whole show for us with every regional dish and delicacy. Devi was the only one who spoke English, so he ended up translating our conversation. He never got a bite to eat that whole morning.

“We found out he had just turned 18, and in Georgia that meant you either go to a university or you go into the army. His family didn’t have the resources to send him to a university, and his father was sweating trying to figure out how to keep him out of the army and getting shot at by Russians. My wife and I said, ‘Look, why don’t we just bring him over to Tech?’”

Devi soon arrived in Lubbock and lived with Mark and Virginia for a time in a spare bedroom.

Mark fondly recalled several nights trying to practice his Russian with Devi. Mark would try a sentence in Russian, and Devi would reply in a mishmash of Russian, English, and any of the other three languages he was fluent in.

Mark may not have become fluent in Russian, but they had a great time talking throughout those nights. They even created their own private language that fused Russian, English and other languages together.

Devi would go on to earn his bachelor’s degree in political science and then interned with Congressman Beto O’Rourke in Washington. He returned to Texas Tech to earn his interdisciplinary master’s degree in international affairs, communications and history.

Devi then spent some time in Los Angeles working on his acting, modeling and music careers. However, as he put it, his brain continued to have an itch he could not quite scratch.

“When you take time to do different things, you realize what you want to focus on,” Devi said. “I realized academia was my thing. Specifically, history.”

From Wine to Identi-Tea

When Devi started working on his doctorate, he knew he wanted to focus on 19th and 20th century European history. It seemed like a natural fit for Devi to study the histories of Georgia and the Soviet Union. The question became how to narrow his focus.

Devi originally wanted to study Georgia’s wine production, but Alan pushed back against this idea. People unfamiliar with Russian, Soviet Union or Georgian history were already aware of and drinking Georgian wine.

Instead, Alan encouraged Devi to explore some Georgian archives and look for a topic that was not as well-known. Devi was up to the challenge.

“He’s done his archival research and exchanges for many years,” Devi said about Alan’s influence and mentorship. “He has conducted extensive archival research in Russia for many years, deepening our understanding of Soviet history and the Gulag system.”

Alan sees value in not only looking at historical success, like Georgian wine, but also apparent failures; he argues there is a lesson to be learned in both.

Devi then secured two smaller grants for separate trips to archives in Georgia. There, he started to uncover the hidden history of Georgia’s tea production.

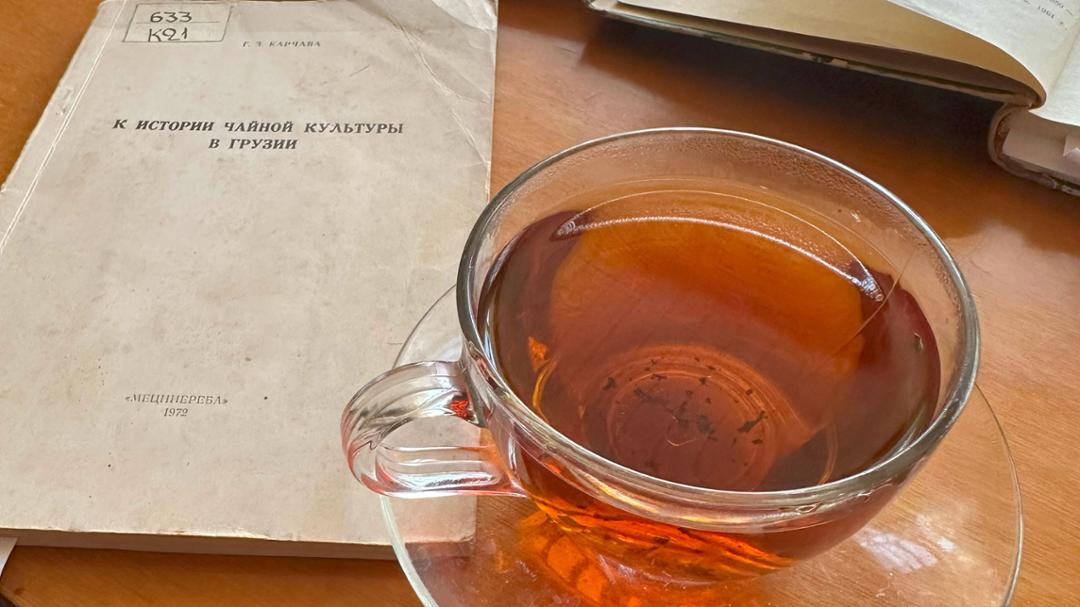

“As a kid, I drank Indian tea or other foreign imported tea, but I never had Georgian tea,” Devi said with a hint of longing. “When I saw the archives, I was like, ‘What tea? We didn’t have tea.’”

The more time Devi spent in the archives and spoke with his family and other Georgians, the more he realized his country had a past that was either not remembered or not being told.

Soon, Devi started to see other ways Georgia impacted the Soviet Union beyond tea.

“Georgia had a lot of hands into the Soviet Union,” Devi said, noting that Joseph Stalin, who led the Soviet Union for nearly 30 years, was Georgian and installed many Georgian elites into key Soviet leadership roles. “When the Soviet Union was creating itself, it needed a culture and a strong identity. They turned to Georgia for that.”

In fact, Devi noted at one point that Georgian recipes were prominently featured in Soviet Union cookbooks. Essentially, “Soviet” recipes were Georgian dishes.

This notion of Georgia being fundamental to the creation of the Soviet Union and the development of its identity was new for someone who grew up in a post-Soviet world.

“I grew up in Georgia, and I thought of Georgia as trying to create something from a poor nation,” Devi said. “A lot of people don’t grasp what Georgia meant for the Soviet Union. I’m trying to contribute not only to Georgia’s history, but also to Soviet history and Georgia’s identity.”

Devi hopes studying tea can brew a modern Georgian identity that acknowledges the influence the country had on the Soviet Union but also celebrates its current culture.

Regardless of which republic the people lived in, the Soviet Union wanted them to see themselves first-and-foremost as Soviets. Many countries and their people struggled to see an identity with the Soviet lens removed after its fall. Forging an identity and casting aside decades of totalitarianism wouldn’t be as easy as flipping a switch to light a room.

Devi looks at other academic efforts to recontextualize a country’s history and its identity as possible roadmaps for Georgia.

Specifically, Devi brought up the book “Que Vivan Los Tamales!: Food and the Making of Mexican Identity” by Jeffrey M. Pilcher. In it, Pilcher examines the ways native foods, flavors and cooking techniques persisted in Mexican culture during and after the colonial period and the specific role women played in this determined preservation.

“I thought that was wild,” Devi exclaimed, “to understand history through consumption. If those women did that for Mexico, what about other countries? What about my country?”

Though Georgia’s current tea industry is a shadow of its former production glory, it is a part of the country’s identity Devi wants to be celebrated, not forgotten.

This is a huge shift from where Devi started, being unaware of the rich history of Georgian tea.

“It’s been really gratifying to see Devi move along the spectrum as a researcher,” Alan said. “He’s already done a lot of research and wrote this compelling grant proposal. It’s very exciting.”

A Year in the Field

Thanks to the Fulbright-Hays Fellowship, Devi will receive funds for one year of research in Georgia starting in February 2025. He will spend his time researching in various archives, visiting old tea plantations and production factories and talking with the workers who made Georgia’s tea industry what it once was.

Devi’s excitement about talking to the workers is palpable. He has visited Geogia twice on previous grants over the course of two years and had opportunities to talk with these workers. But his visits were for a handful of weeks, and the time he had to spend with the workers was fleeting. He often returned home to Lubbock with more questions than answers. Like a strong cup of tea, what he needed was more time.

“They start to sparkle as they remember the good old days,” Devi said, speaking of those conversations. These people are in their 80s and 90s. They each have a story to tell, and I have this urgency to talk to them to get a record of this.”

Devi also is excited to spend time walking the fields of the tea plantations. During his past visits, he walked the grounds of the abandoned or repurposed factories and was transported to a Georgia he could only imagine.

He can easily recall feeling the energy of the past there. He could envision those bustling tea farms and factories with people working non-stop, 24 hours a day. He could feel the pride the workers must have felt knowing how much tea was being produced at that time.

“Tea has so much to say about Georgia, it’s insane,” said Devi. “The Fulbright-Hays Fellowship really has given me an incredible opportunity to dedicate my time without distraction. I’m sure a year still won’t be enough.”

By the end of his year in Georgia, Devi will not only have conducted various types of research into Georgia’s past tea industry, but he hopes to be deeply integrated with the local scholarship by interacting with fellow researchers, attending various seminars and participating in scholarly talks.

Giving Back

Devi is quick to say his work is more than just his research or dissertation. It is a means of giving back to the various places he calls home and the people who have contributed to the person he is today.

People like his family – his mother, father and grandmother – who gave him a foundation rooted in discipline, creativity and courage. People like Mark Webb and Virginia Downs who saw his potential and offered the opportunity to turn his dreams into reality. People like Alan Barenberg who pushed Devi to explore Georgian history in a way even Devi, a Georgian, did not envision.

“The whole village raised me,” Devi said. “In Georgia and Lubbock, it’s the same cultural thing. I just trusted the process from the beginning and took my time.”

For his part, Devi wants to inspire other Georgians and people from other former Soviet republics in a similar way that “Que Vivan Los Tamales!” did for him. He wants people to rethink the ways they understand the history of their countries and their identities.

Looking at tea may be a niche focus area, but Devi sees this as a big first step.

“I want to follow the path of the people who paved the way for me in Soviet Scholarship,” Devi said. “That is my main goal with my research. I want to inspire these new interests and opportunities for people.”

For Texas Tech, Devi wants to give back in more ways than just increasing the university’s notoriety as a Fulbright-Hays scholar.

He wants his research to impact governments and policy. History, Devi believes, should not be hidden from people but made accessible. People learn from history and avoid repeating similar mistakes. Devi sees his work and the work of other Texas Tech history professors as being crucial to making this happen.