A one-word answer from Angela Walla’s grandmother changed the entire trajectory of her career.

It is the early 2000s. The anxiety of Y2K has waned, Carson Daly is still counting down the hits on MTV, and Angela Walla (then Angela Shaw) is in her sophomore year of college at Iowa State University. A pre-vet student, she has just wrapped up an internship at a local zoo and realizes veterinary medicine is not for her.

“I went home and cried to my grandma,” Walla said, who was determined to become a veterinarian prior to the internship. “I thought that was my identity.”

To console her, Walla’s grandmother asked her what the one thing she loved doing most was. Walla, still dealing with the loss of her believed identity, could not answer. Her grandmother wasted no time providing the answer for her: cooking.

This one word that spoke directly to Walla’s personal interest would change the course of her life and set her on a path to becoming a food microbiologist.

Cooking Up an Academic Career

“I got into food safety because of my passion for cooking,” Walla said, reflecting on the impact of her grandmother’s question. “I had taken several microbiology classes, but it never clicked that there was someone who was a food microbiologist that had to make sure products were safe.”

Walla’s passion for cooking was rooted in supporting her family. Walla is the youngest of four children and her parents were often out of the house working. Her father was a pastor and worked logistics for a trucking company, while her mother worked several jobs in the hospitality sector.

Walla chuckled as she recalled her youngest cooking memory. She was 5 years old, standing on a stool preparing some Hamburger Helper. Cooking was always an influential part of her life, but she never imagined it would influence her professional career.

Walla would earn her bachelor’s and master’s degrees in animal science at Iowa State University before securing her doctoral degree in animal science at Texas Tech University in 2010.

After returning to Iowa State as an assistant professor, Walla rejoined Texas Tech in 2022 as a professor of animal and food sciences in Davis College of Agricultural Sciences & Natural Resources.

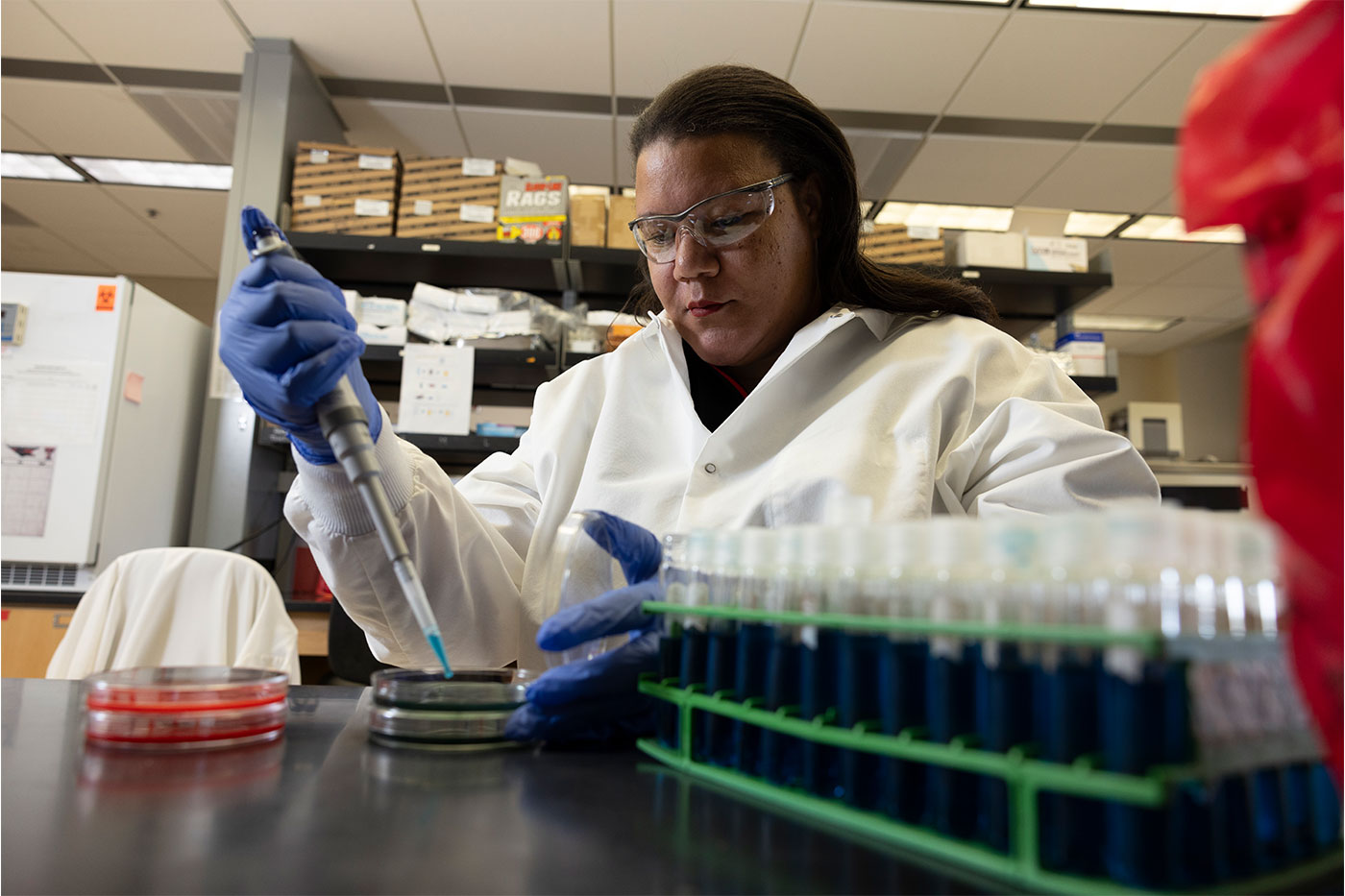

“I work with the retailers, distributors and manufacturers,” Walla said. “I do a lot with training as part of my research, looking into the best methods to train people. As a microbiologist, I purposely put bacteria into food that cause people to get sick and study how the bacteria behave and how we can eliminate them from the supply.”

Walla is also researching the supply chain’s impact on food insecurity. While at Iowa State, Walla had access to one of the largest dietitian programs in the country. As the nutritionists were pushing diets high in vegetables and fruit, Walla was focused on the bacterial outbreaks and food safety concerns making headlines.

“That really elevated my work,” Walla said. “When people want to eat a salad, they need to feel confident that the lettuce, tomatoes, cucumbers and all the other vegetables are safe.”

Walla serves as co-director for the International Center for Food Industry Excellence (ICFIE), housed in Davis College. There, she connects students, industry partners, international governments and other academic entities together.

ICFIE follows the One Health approach, which works to achieve optimal health outcomes by working at local, regional, national and global levels. The driving force of this approach is to examine the way humans, animals and the environment interact and affect each other.

“We want to be that place that brings researchers and different industries together,” Walla said, “to really solve the idea of what is healthy and question how we produce and process food safely.”

The One Health initiative became a driving force for ICFIE, thanks in part to the past government policy work of Mindy Brashears, the ICFIE director and a professor of food safety and public health at Davis College.

Walla, who had been a part of ICFIE as a doctoral student, appreciated the One Health emphasis.

“These problems are bigger than just microbiology,” she said. “We were focusing too much on the food industry, and we weren’t touching back to the farm. We weren’t going forward to deal with the medical industry. One Health requires us to have partners and look at the holistic picture of food.”

Walla’s vision and work at ICFIE are points of pride for Naïma Moustaïd-Moussa, who serves as the executive director of the Institute for One Health Innovation as well as the founding director of the Obesity Research Institute, a Horn Distinguished Professor in the Department of Nutritional Sciences and a professor in the Department of Cell Biology & Biochemistry at Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center.

“Dr. Walla’s leadership and collaborative approach to research are incredibly important,” Moustaïd-Moussa said. “As we continue to explore how plant, animal, human and environmental health are connected, we need institutes like ICFIE and leaders like Dr. Walla who can translate those discoveries into actionable changes that create healthier communities.”

Connecting with Industry Partners

Walla has received over $20 million in grant funding over the course of her career and has tried to incorporate an industry advisory board or another type of stakeholder engagement group with each grant.

Walla chairs one such group focused on controlled environmental agriculture. The industry partners are interested in growing produce in greenhouse spaces due to the lack of available outdoor space.

Walla gives space for researchers and industry partners to come together each month and meet with government agencies.

“That engagement is so important to the research,” Walla said. “We don’t want to just have the data sit there. We want to make an impact, so having those conversations with our stakeholders is important.”

Walla explained that researching a problem and ignoring the context does not make sense. What if she determined one solution for combating E. coli in lettuce, but another problem – say, a lack of clean water or a decreasing workforce – was at the forefront of her industry partners’ minds?

“Workforce is one of those issues that there’s not an easy solution to,” Walla said, “but we know a lot of food safety issues are reflected in the lack of workforce. There are complexities that go with a simple solution of training employees. An employer could say, ‘That’s great, but I’m already down 10 employees.’ These issues are just bigger than what could be solved in a lab.”

Empowering the People

When it comes to her international work, Walla looks to empower the people responsible for farming the food. However, she is cognizant of shedding an ethnocentric mindset before making any recommendations to people or their government.

“I try and respect other cultures as much as possible,” Walla said. “Having translators who truly understand the culture before I jump in and try to Americanize and recommend something is important.”

Walla highlighted a recent project where one of her graduate students studied butcheries in Uganda. The experience was made special because Walla’s student was from Uganda and had the opportunity to give back to their country while assisting in a practical food safety solution for a major food sector.

As the student walked around the market, carcasses of animals to be sold were hung on display at booths.

Walla and the student talked to the people at the booths to better understand the cleaning and food safety procedures and to collect bacterial samples.

With the help of a professor from Makerere University in Uganda, Walla and her student were able to complete a microbial analysis and provide the local government with recommendations for educating its people.

“They had a lot of food safety regulations, but no one was following them at all,” Walla said. “There weren’t enough government people to enforce them, so they needed help with educating the people on the practices.”

Walla credits her love of traveling to opening her mind beyond the food safety practices of the United States.

Walla then gestures toward her shelves loaded with textbooks.

“We have these books,” she said, pausing for a moment, “and they will tell you to only allow food to be cooked a certain way and kept so long. But then we find different cultures do things other ways, and they have completely healthy bodies.”

Walla takes another moment to gather her thoughts. She seems mentally transported to a particular moment in her past – reflecting on how much more research and cultural sharing is needed to truly understand how microorganisms function in different environments globally.

If other countries have different food safety practices, which are the “correct” ones to follow? Is this a matter of being right or wrong, correct or incorrect? How narrow should anyone’s view of food safety be?

“Traveling has made me appreciate different food cultures and the producers who supply food globally.”

Prepping the Next Generation of Food Scientists

As an instructor and mentor, Walla hopes to instill the idea that there are more research questions that require global partnerships and collaborations.

Walla specifically recalled a trip to Honduras for one of her projects.

“I told my students, ‘I need you to listen more than you talk,’” Walla said. “Rather than just point out Americanized food safety issues, I needed them to solve problems in the context of where they were.”

Walla also gives her students an honest impression of what her work in the lab entails. She often will bring undergraduate and high school students into her lab so they can see her at work.

“They get shocked when I tell them an experiment is probably not going to work, and we still have to publish the results,” Walla said.

Walla takes graduate students on international trips and to conferences where they can talk to and connect with farmers or industry professionals who need to make a profit.

“I try to expose my students holistically to research and then get them before the industry. A lot of times students have ideas of what we could do in the lab, but I need them to think about how that solution applies to a farmer. It’s been eye-opening to my students to do the research, present it to farmers and then get questions related to cost and things they’re not thinking about.”

For as much energy and motivation as Walla gets from mentoring this new generation of scientists, being a professor was a path she did not envision for herself.

While working toward her bachelor’s degree, Walla was diagnosed with dysgraphia, a neurological condition that can create difficulties turning thoughts or ideas into writing. To manage dysgraphia, Walla is not shy about relying on proofreaders with her manuscripts or grant proposals.

“When I was initially diagnosed, I was embarrassed,” Walla recalled. “But I learned a lot of people have writing issues that they’re not willing to admit. Now, I talk about it a lot just to normalize it.”

Walla leans on the lessons she learned in managing dysgraphia when working with students.

“We all have things we’re going through, but I tell my students they can still become a professor. I tell them to not let anything hold them back, but that it’s also OK to get help. Over the years, I’ve asked for help more than anything, and I’m less apologetic about it now.”

Making Meaningful Connections

Walla has made it a point in her professional career to teach the next generation to question accepted practices and create unique connections, even if it means slowing down and taking more time.

She demonstrates this to her students through those who work in the lab.

“I think we calculated we have 13 or 14 different primary or first languages spoken,” Walla said. “People are able to come into the lab and say, ‘In my country, we do things like this,’ or ‘In Louisiana, this is how we do it.’ This naturally brings up a lot of questions and thoughts and sharing. I love that.”

Walla has also learned from her students how to make unique connections between her field of study and other academic areas, too.

Walla mentioned one particular undergraduate who worked in her lab. The student was a dance major and wanted to incorporate food safety into her senior dance project, namely keeping safe temperature controls.

“They orchestrated and choreographed a whole dance and had props that demonstrated keeping safe temperatures,” laughed Walla.

She takes a beat. Then, Walla reflects on her conversation with her grandmother. The one that started her on the path as a food microbiologist.

Her grandmother was able to think outside the box and see a potential connection between Walla’s interest in science and her passion for cooking.

“I am a foodie, and I love to travel,” Walla said, who now is joined on her food and travel adventures with her husband, Evans Walla. “I love to try different cuisines and study the backgrounds of other cultures’ traditional meals. My work has allowed me to explore and appreciate people more than anything.”

Walla now tries to connect the interests and passions of her students.

“My grandma was able to have me sit back and say, ‘OK, I can cook all day, every day. How can I connect it to something meaningful?’ That’s what I tell students. Think outside the box of what you may do with your degree because you never know what you’re going to do.”