Jes Deaver, this year’s H. Deane Pierce Endowed Visiting Assistant Professor of Architecture, is combining her love of storytelling, architecture and science-fiction to create a first-of-its-kind student experience.

Designs cover the walls of Room 602 in the Huckabee College of Architecture. At first, they seem like any print-off one might find in an architecture class but upon looking closer, vivid images stand out.

The Leaning Tower of Pisa.

Michelangelo’s “Creation.”

An alligator.

This cacophonic collection is overwhelming at first.

Jes Deaver is leading the class. It’s a graduate-level studio that meets all afternoon, three days a week. The time investment is immense, but the payoff will be remarkable.

Each student has been assigned a science fiction novel to read. The main character of the story will be their “client.”

Instead of presenting their design at the end of the semester, they’ll be required to write a short story illustrating their concepts. They’ve been asked to show rather than tell.

They’ve been asked to become world builders.

“See how simple that is?” Deaver asks her student, Gunner Murrell.

Murrell nods as Deaver applauds the simplicity of a diagram he’s revised over the weekend.

“There is less information here, but it’s clearer. That’s what your client wants,” Deaver says.

Although Deaver is teaching a design studio that layers complex concepts with tough technical applications, she is a believer in simplicity. She is a believer in small things.

From visiting Texas Tech University’s campus as a kid to becoming this semester’s H. Deane Pierce Endowed Visiting Assistant Professor, it’s this mindset that has brought her full circle.

Her Place in the Universe

Deaver didn’t dream of being an architect when she was young, and simplicity was not her mantra. She loved telling stories and exploring the world around her.

“I wanted to make an impact,” she recalls.

This dream was shaped by early visits to Texas Tech’s planetarium. West Texas already had an expansive horizon, but when she stepped inside, Deaver’s imagination expanded like the unfathomable firmament above.

She visited Lubbock in the summers, and her grandfather Robert Morris Middleton would take her to campus.

“He was a bricklayer for several of the buildings at Texas Tech,” Deaver says.

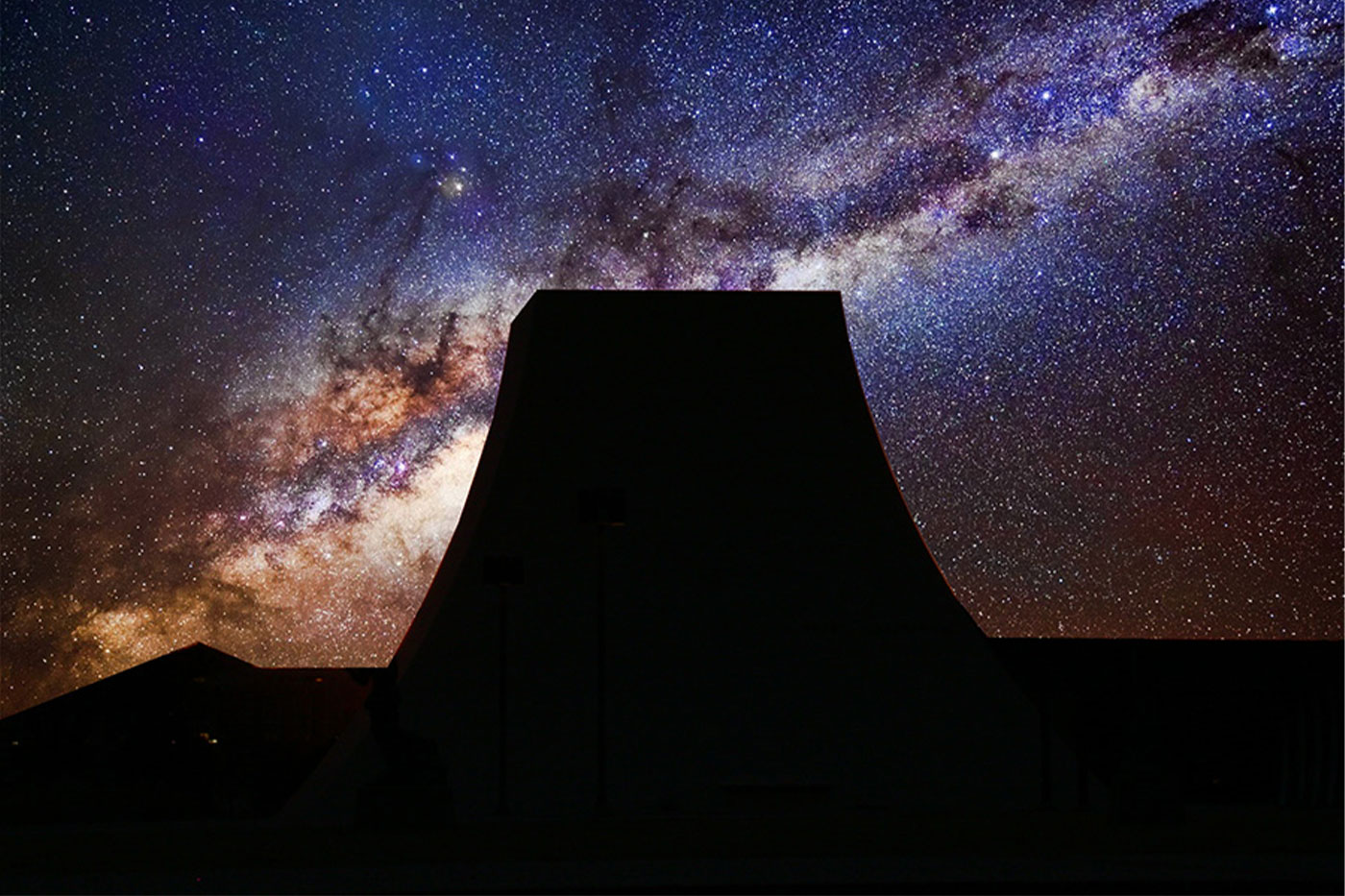

While Middleton helped assemble campus throughout the 1960s, his favorite building to visit was Moody Planetarium. The sloped building on the north side of campus was a refuge from the bright, hot summer days. He took Deaver to the planetarium and they’d lose sense of time, beholding the celestial wonders around them.

“My grandfather was a man of few words,” Deaver says. “He was the kind of person who’d stand outside on the back porch and stare at the stars. I think I shared that with him in subtle ways, that desire to have a bigger understanding of my place in the universe.”

Deaver looked to storytelling to do that.

She imagined being an actress, a screenwriter or even a novelist. Architecture was not in the blueprints.

Her father Nick Deaver had achieved success in the architectural world by the time his daughter was born. He earned his Bachelor of Architecture at Texas Tech where he recalls professors approaching the practice as more than a career, but a lifestyle.

After graduating, his moved to New England. Jes grew up in Connecticut, save those summers spent with her grandparents in Lubbock. But by the time she started high school, her father was yearning to move back to Texas. They relocated to Austin where Deaver eventually went on to attend The University of Texas (UT) at Austin and earned a Bachelor of Science in Film with emphasis on radio and television.

“I always loved telling stories,” Deaver says.

Her father noticed her early interests.

“My artistic skills were studied and acquired but Jes’ talents were organic,” Nick says.

He says his daughter had great empathy for people from a young age and often succeeded not only because of her skill, but because of her will.

“Her spirit tends to be noticed wherever she goes,” he added.

Throughout high school and college, she could be found scribbling out short stories, scripts and even plays. Before landing at UT, she studied acting at St. Edwards University. After interpreting others’ work, she realized she desired to create stories herself. She began working on film sets after graduating. A gig for “Austin City Limits” here and a gig for Ford Trucks there, eventually led her to New York City.

Deaver immersed herself in the film world, taking the wide universe and placed it into a narrow lens. Her work took her to film festivals and allowed her to meet many kinds of people.

By 2008, she was working for a camera house in New York. Her job had shifted away from the creative work of making films to more technical work. Something within her felt unsettled. Then, the financial crisis of 2008 hit. The film industry suffered, and she felt her best option was to move home.

Nick had established a successful architecture practice in Austin by this time. He invited his daughter to help him, creating films and other story mediums to communicate the importance of what architecture was accomplishing.

At some point behind the camera, she began entertaining the idea of a career change.

“I was learning how to tell stories about architecture at the time, so it was my first step into that world,” she says. “It meant a lot to me and my father to do that together.”

That became the foundation of her wanting to work with Nick full time.

“I worried if I would be any good as an architect,” Deaver recalls. “But I knew I wanted to elevate Nick’s legacy.”

Turns out, she had quite a knack for architecture.

Deaver, in her early 30s, redesigned her life. She earned a Master of Architecture from the University of Houston while remaining as active as possible with her father’s firm. Once she obtained her degree, she knew it was important to get experience outside of Texas, so she moved to Los Angeles. There, she worked for Pfeiffer Partners and collaborated on teams designing civic projects such as theaters and libraries.

Outside of work, she could often be found studying the stars at Griffith Observatory, an architectural wonder built in 1935 and remodeled by Pfeiffer Partners in 2002, that makes astronomy accessible to the public. Nostalgia around those nights under the West Texas sky with her grandfather came rushing back. That insatiable need to connect to something bigger came back with it.

A few months later, Hurricane Harvey pummeled southeast Texas.

“I realized architecture was more than building a powerhouse,” she says.

Her focus shifted back home, to helping cities and communities that had impacted her.

Thus “Nick Deaver Jes Deaver Architecture” was created.

“Jes is not only my daughter; she’s my partner,” Nick says. “Architects can destroy worlds or create worlds. Jes, through her architecture, is making this a better world.”

Off the Page

Today, Deaver is an award-winning architect who has turned her passion for architecture and storytelling into a unique career. She loves reading science-fiction, she owns clothes covered in dinosaur print and she visits NASA for fun.

“Gosh, I’m such a nerd,” she laughs, shifting her cup of coffee from hand to hand.

She’s walking alongside a reflection pool by Moody Planetarium, still her favorite place on Texas Tech’s campus. She comments on the friendliness and the warmth of the people at Texas Tech. It’s a reminder of her past, but as ever, it’s a place to ponder the future.

“Architecture can be very past-focused,” she says. “There are a small number of practitioners in the world who are trying to push that boundary.”

Deaver is certainly one of those people, and it’s the reason Huckabee College of Architecture has brought her on as faculty this semester. But her approach to future-focused design is a bit peculiar.

“One day I started thinking, ‘What if science fiction could be a lens to look at where we’re headed?’” she says.

Since the genre often pulls from current society and imagination to project the future, Deaver wondered how it could be paired with architecture.

Her gray-blue eyes brighten as she talks about 3D printing, “Jurassic Park” and spaceships. Michael Crichton’s zoological harbinger was the story that got her hooked on science fiction as a young girl. Her repertoire of favorites has now grown to include favorites like “The Drowned World” by J.G. Ballard and “Wool” by Hugh Howey, and she’s even published her own short story “Zero: Emancipation” in Texas Architect.

These tales fall under a science-fiction subgenre known as climate fiction, or cli-fi. It is these stories that create the foundation for her graduate studio at Texas Tech.

“My students are designing single-family residences,” she says. “They have each been assigned a cli-fi novel to read. The main character in their story will be their client for the design they’re creating this semester.”

The seemingly disjointed images of The Leaning Tower of Pisa, Michelangelo’s “Creation” and the alligator begin to make more sense. Each is a critical scene of a book.

No matter the character in their books, each student has the same building site: Buffalo Bayou in Houston. The coastal city also is the setting of Deaver’s published short story. The site has become especially meaningful to her after Hurricane Harvey.

It’s a site important to the students as a few of them are from the Houston area.

“I wanted students to work with an immediate environmental danger,” she says. “Our site is adjacent to the bayou. While surrounded by marsh and water, the site also is unique because of the remnants of industry present in the empty silos that stand in the middle of the field.”

Tall, looming ghosts of times past, there are trees that grow up the middle of the empty silos. Students will have to incorporate these towers into their designs. The group just returned from a weekend trip to Houston where they got to walk the site and gain a deeper understanding of the wetland ecosystem.

Gunner Murrell is designing a house for the main character of “Wool,” named Juliette.

“She’s lived her whole life underground. She’s never even seen a sunrise or sunset.”

Murrell is working on a design to transport her.

“My character is hands-on and practical,” he says. “Those are things to keep in mind while designing for her.”

While Murrell wants to create an introduction to the natural world for his client, he also knows it needs to be simple. The second-year graduate student already works part time for a residential architecture firm in Lubbock, and he’s considering continuing down that path after graduation.

When enrollment for Deaver’s studio opened, Murrell decided to try it.

“It sounded unique from the typical flow of studio work,” he says. “This was going to offer a special perspective. The climate-fiction reading and writing breaks the norm of what we do.”

But Murrell sees that as a positive thing.

“An innovative class like this adds to my education,” he beams. “It’s allowing me to consider new perspectives, and I believe it will help me better serve clients in the future.”

When Deaver announced the class, she was unsure if anyone would sign up. But when registration closed, there were more than a dozen signed up, pushing the limit for a graduate studio class.

“Jes Deaver brings an excitement and a fresh perspective to our graduate students,” said Huckabee College of Architecture Dean Upe Flueckiger. “She opens the students’ eyes and makes them look and see architecture they haven’t thought about before, which is a gift not only for the students in her studio but for all of us in the college.”

The Biggest Ripples

At the end of the semester, Deaver’s students will read their short stories to the class.

“If there is an element vital to their design, it better be a big part of that story,” Deaver emphasizes. “I’m asking them to communicate their design in a creative way, so they learn to talk about architecture in ways that connect with the public.”

According to Deaver, architects are some of the most brilliant people she knows, but they often struggle to communicate their ideas. As someone who’s had a passion for communication her whole life, this is something she hopes to offer her students.

“My father impressed upon me, ‘Speak plainly so your clients understand you,’” she says. “I think part of that comes from the humble background my family had in West Texas.”

She raves about her father’s designs that connect to the land and are unique personal expressions of his clients.

For Deaver, her journey back to Texas Tech has been marked by one big change.

“I still want to have a big impact, but I’m going to do it in small ways,” she said. “The further I’ve gone on my journey, the more I’ve discovered how the biggest ripples are made with the smallest stones.”

Similarly to her grandfather who laid campus brick–by brick, his granddaughter is building student–by student.

Murrell is a living example.

“I’ve never studied under someone so passionate,” he said. “I see the ripples of this already. When I was a first-year student I felt so in over my head. Now, I’m inspired to take risks. Nothing feels too big.”