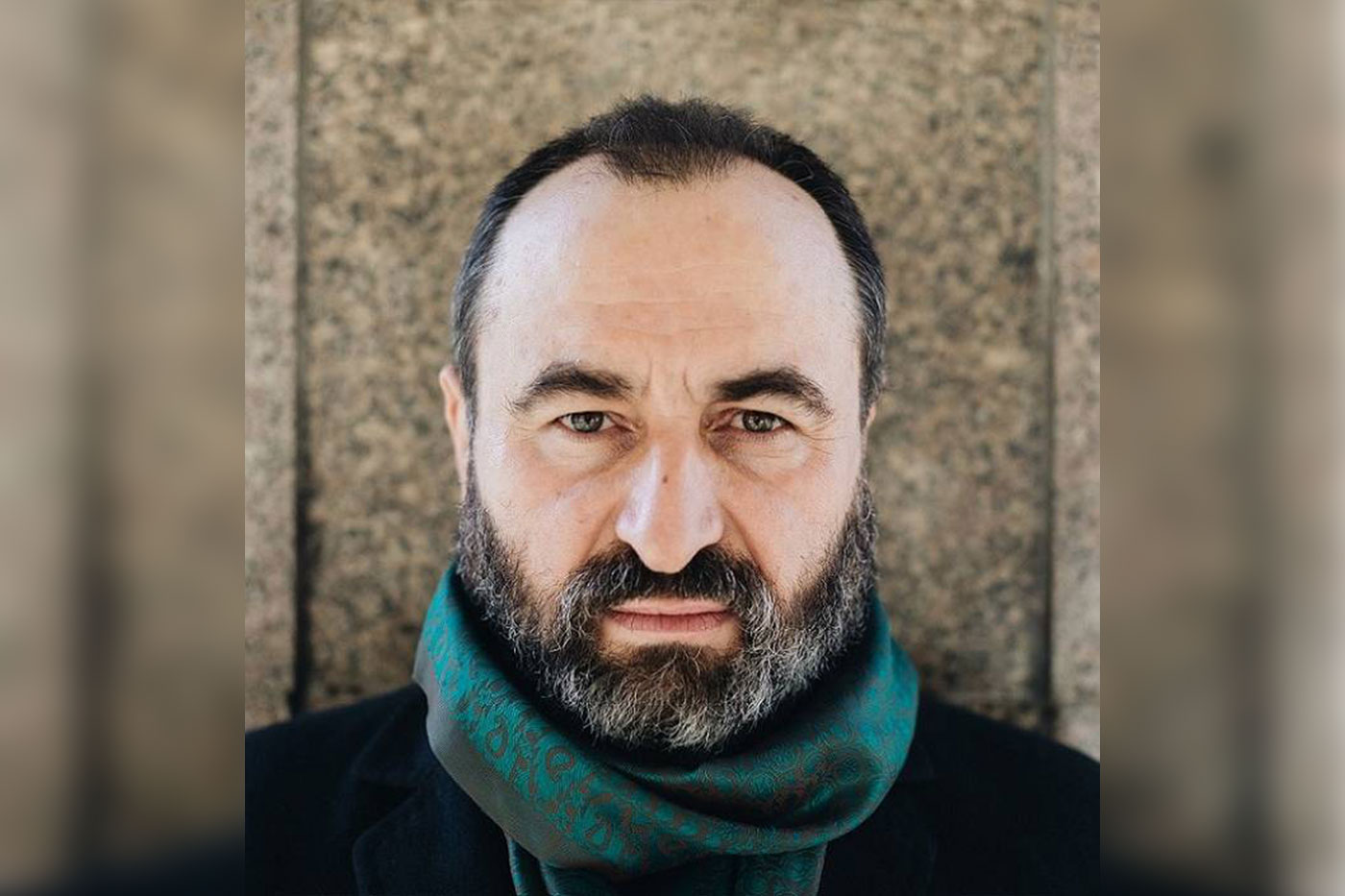

Costică Brădăţan is abroad for the second straight year as part of the Fulbright U.S. Scholar program, developing a book chronicling dissent in Western philosophy.

The internet is a world where an innocent post declaring affinity for pancakes can meet the fierce protest of, ‘Why do you hate waffles?’

In some instances, dissent seems to appear just for dissent’s sake. Opposition can resemble more of an annoyance than a vital key to societal progress, but one Texas Tech University professor views the concept differently.

“It's fundamental that there is always somebody who goes against the mainstream, the conventional wisdom, what's accepted and acceptable,” says Costică Brădăţan, an Honors College professor of humanities. “You always need this kind of challenge coming from outsiders, from dissenters, from provocateurs, because this way you ensure a certain degree of freshness of intellectual dynamism, of intellectual progress.”

Brădăţan argues complete agreement means people don’t see the need for progress or room for improvement.

“Everything gets frozen,” he adds. “It stays in place.”

Last spring, Brădăţan was named a recipient of the 2024-2025 Fulbright U.S. Scholar fellowship, just the latest achievement for the Romanian transplant in the last year, as it marked a rare occasion of receiving the fellowship in two consecutive years. This February, Brădăţan was also named a Horn Distinguished Professor, the highest honor a Texas Tech professor can receive, as a result of their attaining national and/or international recognition through scholarly excellence.

Since 2023, Brădăţan has been diving into the concept of dissent in his country of birth as he develops his book “The Herd in Our Head,” which discusses dissent’s cultural function and philosophical significance.

The book is a natural continuation from his previous book on failure. He realized dissenters, while in some cases extraordinary successes, were all at some point labeled failures or losers for their unwillingness to conform and be silenced.

The process has been six years in the making, starting with his publication of the essay “How we fail and why” in the Los Angeles Review of Books in 2017.

The reception that followed gave Brădăţan the impression that his idea had lasting impact, and soon after, Princeton University Press offered to publish a book expounding on the essay.

This was a repeat of what occurred with his previous book released in 2023, “In Praise of Failure: Four Lessons in Humility.”

“You bring something into the world, and you see how people react and gauge what's the worthiness of that project, whether there’s a book to be made or if it’s just something small,” Brădăţan said. “It’s a testing ground. I've been publishing essays for that purpose for a while.”

Brădăţan is all too familiar with life without dissent, growing up in Romania during the brutal rule of Communist leader Nicolae Ceausescu that strongly discouraged any form of opposition.

His Eastern European childhood added an unforeseen layer to The Herd in Our Head.

Brădăţan initially set out to chronicle dissent in Western philosophy, starting with the Greek provocateur Diogenes before jumping forward to the documented arguments from Baruch Spinoza (17th century), Jean-Jacques Rousseau (18th), Friedrich Nietzsche (19th) and onward. The book will include five chapters structured in the form of acts of a classical tragedy, to appeal beyond the academic community, but Brădăţan didn’t plan on one of those chapters wrestling with Eastern European culture in detail.

That changed when he was reflecting on intellectuals in then-Czechoslovakia, Hungary and Poland who “shattered the artificial consensus” of public opinion shaped by Soviet-style governments during the Cold War.

That and the inclusion of Spinoza prompted the realization Brădăţan needed to extend his stay in Romania, a natural consequence of conducting in-depth research that unearths new concepts and can throw original plans off track.

“When projects become more complex, you have a choice to not go there, which comes with the feeling of frustration, or to do it, prolonging the duration of the project and making it more demanding and time-consuming but with the promise of a better outcome,” said Brădăţan.

He certainly was in unfamiliar territory applying for a rare consecutive Fulbright fellowship, but those circumstances made receiving the approval mean that much more.

The project hasn’t garnered nearly as much support in the U.S., so Brădăţan took the opportunity to stay on in Romania as an encouragement. It’s also a reflection of Europe’s aptitude in handling dissent as opposed to the U.S., he said.

“These kinds of conversations can be uncomfortable and nerve-racking,” Brădăţan continued. “People don’t want to place themselves in uncomfortable situations.”

Discomfort will emerge in his critique of contemporary American academia, which will be in the final portion of “The Herd in Our Head.” As an immigrant to the U.S. in 2000 after earning a doctorate in England, Brădăţan eventually grew to see a painful sort of uniformity in the academics around him.

People preferred not to be challenged by other distinct experiences and worldviews and avoided exerting the effort required to truly embrace diversity.

While the book won’t be a direct chronology of Brădăţan’s experience, he sees a story like his own inside, one of an immigrant who learned English later in life and had to make his way in an educational system completely unlike where he came from.

“Coming into the American academic system with no American degrees puts you in a really tough spot,” Brădăţan said, laughing. “I also come from rather humble social conditions, so I think I have some story to share.”

Romania has served as a home base throughout his Fulbright experience. From there, he’s traveled to nearby countries to research authors and stories around Eastern Europe.

Brădăţan has had the chance to speak with numerous scholars about his project, which has spurred on his work. Feedback differs depending on the age of whom he’s speaking with, as elderly scholars who lived under Communist rule into their adult years have a vastly different understanding of dissent and can relate it to contemporary politics.

All those discussions are a reflection of philosophy’s peculiarity as a subject, underlining its importance to society.

“If intellectual challenge comes from anywhere, it’s philosophy,” Brădăţan said. “The other disciplines tend to agree. To make progress in the sciences, a team of researchers coming from different places has to agree on a lot of things, such as methods and protocols.”

Conversely, philosophy thrives on disagreement. As Brădăţan recounts in his book, the vocation has centuries worth of history including philosophers being different in meaningful ways, not arguing just to argue, but with a deeper understanding of their approaches and intentions.

Though communities typically aren’t happy to be challenged in their ways of thinking, philosophy introduces novelty to discussions that allows societies to discover new ideas and solutions.

Brădăţan knows firsthand communities ossify and die when dissent is stifled.

“To be alive, to be prospering, to be thriving as a community, you need to have that dynamic, that mix of ideas, views, people, cultures and so on,” he said.