Natasja van Gestel has invested years of meticulous scientific effort studying a portion of the largely unexplored and isolated continent.

Literally, Antarctica is the last place Natasja van Gestel ever thought she would find herself.

It is remote and inhospitable, windblown and frozen, mysterious and foreboding. Other than a small portion of the international science community, the continent is uninhabited, unless you were to count a handful of various penguin and seal species.

Still, van Gestel found herself drawn here more than a decade ago. The associate professor in the Department of Biological Sciences within the College of Arts & Sciences at Texas Tech University was fascinated by the secrets Antarctica held and made up her mind one day that it would be the place to conduct research, unlikely as it might seem.

“I would never have foreseen this happening to me,” van Gestel said via email after safely arriving at Palmer Station on the Antarctic Peninsula home to a panoply of scientists from around the world.

“Antarctica is such an enigmatic continent, which is largely unexplored. Growing up, I wanted to be an explorer too, but I would not have imagined going to Antarctica even once.”

Once? Are you kidding? How about four times? Van Gestel just returned to Antarctica in time for the austral summer, arriving at the southern end of the world in late October. The demanding trip took a week, and she will remain there for six months.

This time, though, van Gestel carries a title besides Texas Tech researcher. She has been named Palmer’s Science Station Leader by the National Science Foundation (NSF), a prestigious honor that includes significant duties and responsibilities.

According to an announcement from the NSF, van Gestel is the organization’s Office of Polar Programs agent for scientific leadership and mediation. As such, she is charged with coordinating and implementing the United States Antarctic Treaty Program research on station and in the operational area. Additionally, she is responsible for the conduct of deployed science personnel in accordance with the Polar Code of Conduct.

“To be designated Station Science Leader is a distinct honor, both professionally and personally,” she said. “I am a representative of the National Science Foundation, the federal agency that is funding my Antarctic research.”

Van Gestel’s research focuses on how environmental changes influence ecosystem function. During her time there, she has studied Antarctic plants and microbes. In addition to continuing her own work, this expanded new role requires her to work toward ensuring the success of other researchers, despite the challenges of limited resources.

“I may be called upon to make some decisions as to what groups have priorities should the occasion rise,” she said. “The research on station would not be possible without the help of Antarctic support contractors, so I am also the mediator between the grantees and the contractors to help implement the research.”

In that capacity, van Gestel works closely with the Palmer Station manager and the laboratory supervisor.

“Having a leadership role such as this will help me further grow professionally,” she said. “As Station Science Leader, this will certainly bring more recognition to Texas Tech University, both nationally and internationally.”

Now, she finds herself right where she wants to be, having originally been drawn to Antarctica more than a decade ago.

Back in the summer of 2011, van Gestel and her husband read Fen Montaigne’s book, “Fraser’s Penguins,” which focused on the ice-dependent Adélie penguin and how over the course of time the species moved from being practically the only one in the Palmer area of the peninsula to one facing challenges.

“We felt the urgency to travel to Antarctica as tourists to witness it before it changed further and made plans to go in November that same year,” she said.

Before those plans could take place, though, van Gestel traveled with her husband on sabbatical at the Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies in Millbrook, New York. And while they were there, had opportunity to attend a guest lecture by none other than Montaigne himself.

Additionally, they heard a guest lecture from Hugh Ducklow, who was then lead principal investigator of long-term research initiatives at Palmer Station. It seemed like all signs were suddenly beginning to point toward Antarctica.

“What stuck with me from his lecture is all the amazing science done at Palmer Station, though very little terrestrial work,” she remembered. “Hugh Ducklow offered me a chance to go to Antarctica to conduct an independent project to learn more about the plants and soil.”

Van Gestel accepted the offer and joined Ducklow’s research team in 2013, two years after her tourist’s visit to Antarctica, setting the stage for what would become an impressive array of work there.

“It was completely fortuitous that we happened to be at the right place at the right time to meet the right people,” she recalled.

During her first trip as a researcher, van Gestel collected data on the microbiomes of the terrestrial environment as she worked to learn more about what organisms made their home in the unforgiving Antarctic soil.

Since then, she has studied how changes in environmental conditions affect the carbon balance of ecosystems.

“Globally, soils contain over three times as much carbon as what is in the atmosphere,” she said. “What happens to the carbon stored in the soil as conditions continue to change? Could it lead to more carbon being released from the soil and potentially intensify environmental shifts.”

She says Antarctica has a simplified ecosystems with few players in the carbon cycle, making it an excellent model to work in and test hypotheses.

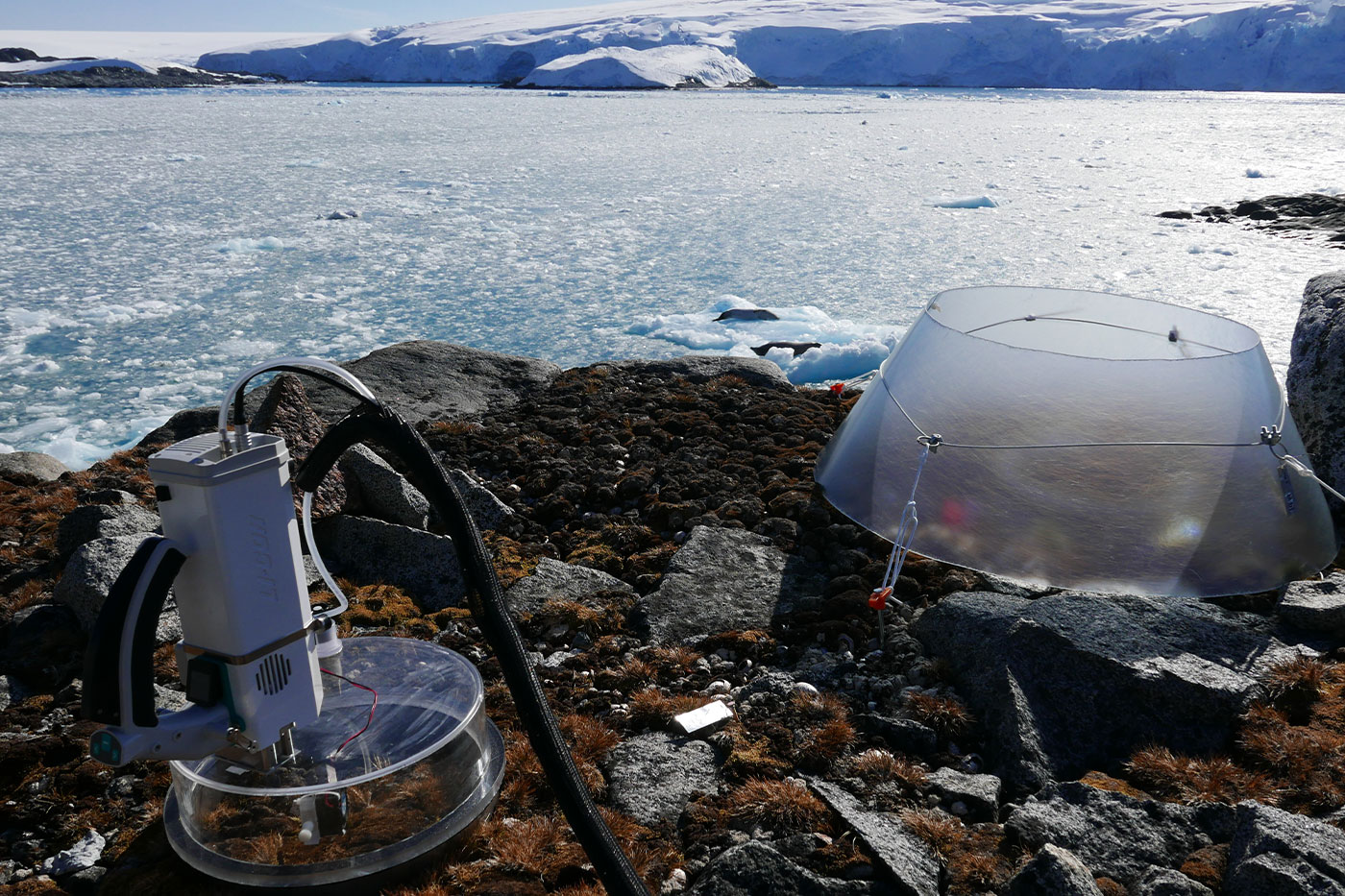

Since 2019, she and her students have conducted field warming experiments and measured incoming and outgoing carbon fluxes. They have observed that the moss experiences stress in response to certain environmental changes, a surprising finding given the cold landscape.

“As a result, with warming, the mosses do not take up as much carbon compared to those in the control area,” she said. “I believe this stress may not be a direct result of temperature change, but rather an indirect effect, such has reduced moisture availability.”

Sara Bohi, a graduate student assisting van Gestel, is investigating which genes are expressed differently between moss in the ambient conditions and those in altered environments to better understand why the moss responds the way it does. Another student working with van Gestel is Tiego Ferreira de la Vega.

At the same time, in their efforts to explore whether moisture levels contribute to the reduced carbon uptake, they are conducting an experiment in growth chambers while keeping moisture levels consistent. Bohi will analyze the growth chamber data for her thesis.

That important work is only a small sliver of the research taking place at Palmer Station. There are four science groups on site now with another expedition set to arrive in January. All are part of the Palmer Station Long-Term Ecological Research (PAL-LTER), which has studied the marine ecosystem on the western Antarctic Peninsula for the past three decades.

“The beauty of it is that each science group examines a different aspect of the marine ecosystem to get a broader picture,” van Gestel explained. “Hence, we have groups examining ocean physics and chemistry and their effects on phytoplankton, which is at the base of most oceanic food webs, and other forms of life are dependent on them.

“Having a 30-year record of all these components is remarkable and has taught us much about the functioning of the marine ecosystem near Palmer Station.”

Each time van Gestel travels to Antarctica, she is reacquainted with its amazing topography and revels in the opportunity to be part of a select group of international researchers deployed here.

“I am thrilled to be part of the science community in Antarctica,” she said. “I also respect and appreciate the fact that scientists from different nations conducting research in Antarctica have a united goal of learning about Antarctica. No matter the political or cultural differences, to be an Antarctic scientist is to be part of something greater.

“I started out as a lab technician at Texas Tech and now I am the NSF representative to a remote and majestic place in the world. I think that says something about my personal drive and ambitions, but it also says something about the support of the department and the university as a whole. Together, we made it possible.”