Rebecca Beals found a passion for teaching while earning her graduate degree at Texas Tech; now she teaches jewelers from around the world.

If you’ve ever bought a diamond, you’re likely familiar with the Four Cs.

Color, Cut, Clarity and Carat.

It was the Gemological Institute of America (GIA) that developed the Four Cs, now the standard for diamond assessments. Texas Tech University alumna Rebecca Beals joined the GIA faculty in 2022 and played a vital part in rewriting their curriculum.

She began her career 10 years prior as a bench jeweler. Beals became an artisan engaged in painstaking and detailed work; a profession she says was a good fit for her personality. To the common eye, a jeweler’s bench can appear disorganized and dirty. But to someone with a trained eye, it’s an altar of dazzling possibility.

The Natural World

Beals grew up in Johnson City, Tennessee, a small town nestled in the foothills of the Great Smoky Mountains. She was fascinated with the natural world, life’s unceasing cycle, and the human body. She was as comfortable talking about the branches of a spruce-fir as she was the human skeleton.

Her father was a doctor and her mother was a nurse, so there were plenty of medical textbooks throughout Beals’ home. It wasn’t uncommon dinner conversation to hear about cases.

Beals spent time looking through anatomy books, thrilled by the mechanisms that make up the inimitable infrastructure of the human body. A lover of art, she spent a great deal of time drawing and painting the images she saw in the books.

“There was an illustration of the human spine I got especially obsessed with,” she recalled. “I would zero-in on each vertebra and try to replicate it with my pencil.”

As college approached, she considered a future in art. She wanted to do something creative but couldn’t see herself in the galleries of Los Angeles or SoHo. As she flipped through the course catalog of East Tennessee State University (ETSU), she noticed a jewelry making class.

Beals loved jewelry but had never considered it an artform like painting. She looked down at the sapphire ring she’d received from her father – a reminder of when they brought her home from the hospital many Septembers ago.

She was surprised a class existed where she could make something like her beloved ring.

“Why did no one tell me about this?” she remembers thinking.

As Beals enrolled at ETSU, she signed up for a jewelry making course. She remembers piercing with a saw and becoming totally enamored with the trade. It was art, but it was also a delicate procedure, almost like surgery, which she heard about growing up.

“Then I got to solder, and I was really hooked,” she laughs, “I was like, ‘I can use fire to make metal do whatever I want.’”

It was a new way of working with her hands, one in which she could see a future. During undergrad, she studied under Mindy Herrin-Lewis, a figurative artist and metalsmith. Herrin-Lewis had earned her Bachelor of Fine Arts from Texas Tech and, according to Beals, went on and on about some master of the industry named Robly Glover.

Texas Tech

Glover, it turned out, wasn’t a mythical legend, but an original tour de force in the world of jewelry, who’d taught at Texas Tech for years.

As Beals’ undergraduate career came to a close, she was interested in a Master of Fine Arts, but she was unsure whether to get real-world experience first. When she graduated from ETSU in 2008, the economy made the decision for her.

“No one was hiring,” she recalled. “So, in 2009 I started my graduate work and moved to Lubbock.”

The flat horizon and lack of forestry was a shock. However, Beals soon noticed the natural world of West Texas had gems of its own. While walking across campus, she noted the seed pods that fell from the sycamore and oak trees. The acorn caps that fell to the ground, brown and cracked, were perfect to collect and connect in descending size. They reminded her of the vertebrae she drew as a child.

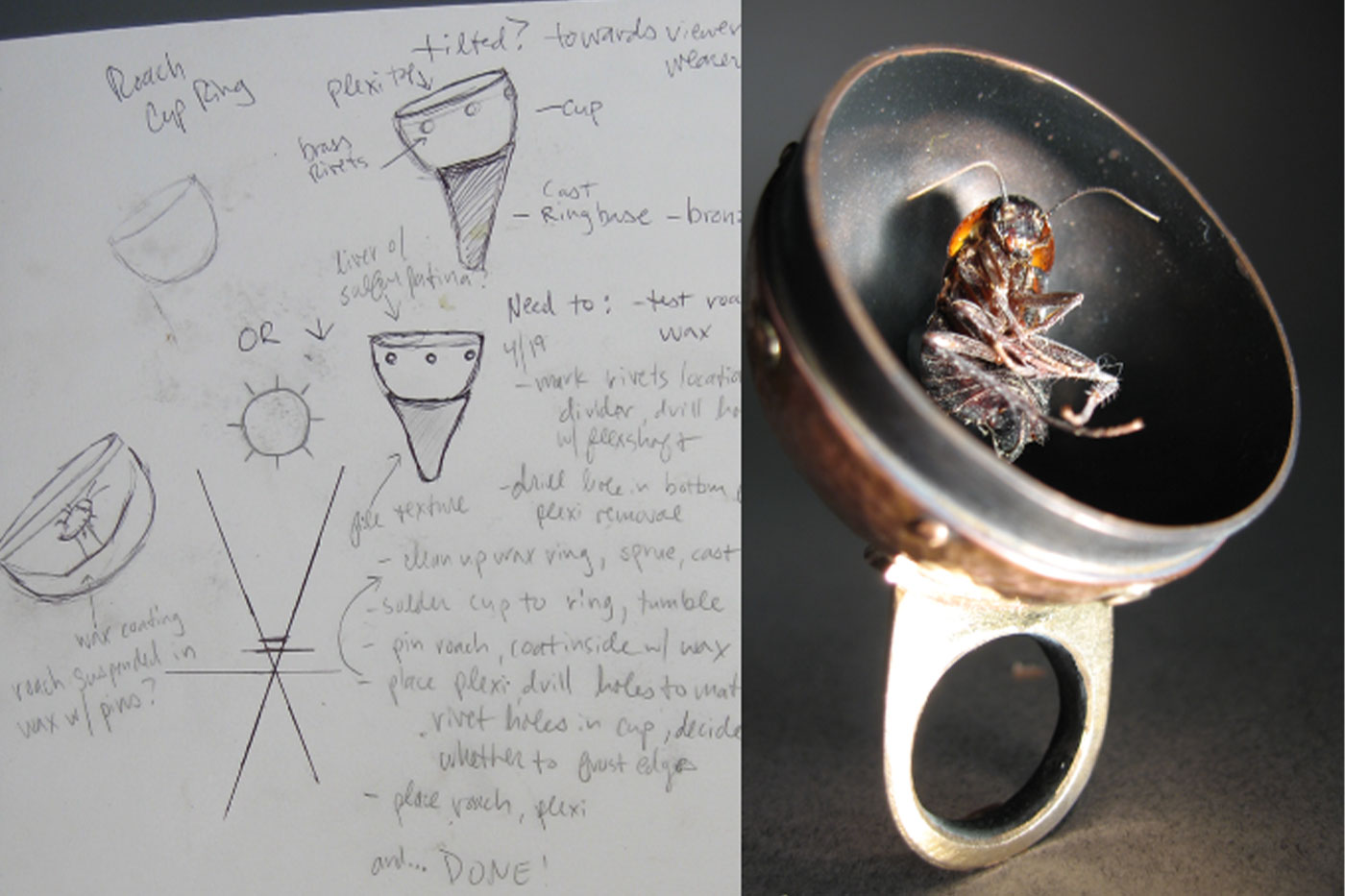

From there, she got the idea to create a collection of art that mimicked the human body and the natural world. This return to her early interests became her thesis. From the living spine to a necklace that modeled an ancient Egyptian funerary broad collar, to a ring whose centerpiece was a cockroach – Beals created jewelry that subverted expectations. Beyond her portfolio though, there were other elements of the graduate experience that stood out to her.

One of those was the amount of teaching she got to do. She taught multiple undergraduate courses, setting her up nicely for what she does now.

“Rob was an instrumental mentor and guided me, inspired me and held me accountable,” she added. “He taught me how to be more detail-oriented and helped me find great scholarships and put together a portfolio.”

An Unexpected Turn

Beals graduated from Texas Tech in 2012 and moved back to Tennessee to finish her training with a few months at the New Approach School, a facility that enhanced Beals skills to the point of becoming a bench jeweler.

She still remembers getting her first job.

“It was exciting, I got paid to make jewelry and had benefits and a 401K,” she laughed, thinking back to her early career.

The job was incredibly hands-on which she loved, even with dust and particles flying every which way. She spent the following seven years working at a variety of stores – some mom-and-pop shops, then trying her hand at big box stores. Beals wanted to get as much experience and exposure to different environments as she could, learning what made her tick.

She loved bench work, but she missed the teaching she did at Texas Tech. As she was reminiscing and beginning to think about where she might be able to integrate her passion for teaching, life went off track.

In January 2018, Beals was driving on one of the many winding roads common in Tennessee, when she lost control of her vehicle.

“I took my eyes off the road for just a moment, and when I looked up, the road was curving and I wasn’t curving with it,” she said.

Her car went off the road into a field below. Beals’ seatbelt saved her life; however, the lap strap applied such force that the L3 vertebrae in her spine exploded. She was taken to Vanderbilt University Medical Center, where the surgeon said he’d never seen a vertebrae trauma so severe that it didn’t leave the patient paralyzed from the waist down. In the doctor’s opinion, it was nothing short of a miracle Beals had function of her legs.

Beals’ career took the backburner while she worked through rehabilitation and recovery.

As she learned about her spinal injury, she recognized the uncanny coincidence of her early fascination with the spine. The images she’d drawn as a child were now constantly in front of her in X-rays.

Five of her vertebrae were now fused together.

Only 30% of her L3 had been salvageable, so the two vertebrae above and the two below were used to support the reshaped one. As she witnessed her spine becoming a new version of “whole,” she was reminded how central it was to everything. There wasn’t one part of the body it did not effect. Perhaps this was why it always had fascinated her.

As life forced her to return to the basics, her career followed suit. She’d had almost a decade of success as a jeweler, and with her new lease on life, she wanted to pay that forward.

“I’ve done well for myself, and that’s part of why I wanted to teach,” she said. “I love seeing the light in someone’s eyes when they figure something out – when they conquer a challenge.”

As luck would have it, a friend of Beals’ who was also a Texas Tech graduate, had taken a job with the GIA. The two of them chatted over social media one morning, Beals congratulating her friend on the new gig, when the friend mentioned other openings for instructors at the GIA.

Beals was in line at McDonald’s getting breakfast when she read the message.

“I grabbed my Egg McMuffin and hashbrowns and went home to apply immediately,” she recalled.

The GIA saw Beals’ passion and expertise and offered her a job at their location in Carlsbad, California, where she’s worked for the past three years.

A Momentous Assignment

Beals now teaches graduate jeweler classes at the GIA, along with continuing education workshops in the same department. The GIA offers programs in jewelry manufacturing, gemology, and jewelry design and technology. The disciplines are related and work together but allow for students to focus on distinct disciplines.

The GIA is a global nonprofit that helps increase public trust in the value of gems and jewelry. The organization produces grading reports for a stone when it is sent in, so the owner knows its gemological properties. It was founded in 1931 and has locations in California, New York City, Thailand, China, Taiwan, India, Japan, Dubai, Botswana, South Africa and the U.K.

Beals enjoys showing students the wide variety of tasks that go into jewelry making such as soldering, filing, sanding, setting stones, polishing, electroplating and countless other skills. Students enroll to further their own careers, many coming from family-owned businesses.

“As an instructor, I am demonstrating a wide range of techniques I learned as a professional, but also during my time at Texas Tech,” she said.

In October 2024, Beals brought those skills back to her alma mater. She spent a few days with students in the Jewelry Design & Metalsmithing program in the School of Art.

“During last year’s Texas Metals Symposium, Ms. Beals gave a lecture on her career and gave critiques for undergrad students,” Glover said. “It was great to see how she has continued to mature in her teaching and professionalism after graduate school. I celebrate her career and can’t help but have an extreme sense of pride.”

Beals says she found the students to be enthusiastically engaged.

“It made me miss being here,” she said. “I miss Texas Tech and the 3D Art Annex. The people here are just the best.”

Beals brought plenty of jewelry with her for students to see. She also brought packets of raw material and challenged students to create a statement piece with only what was in the packets.

But the item Beals was most proud of was the recently rewritten GIA curriculum.

“The GIA textbooks are the gold standard of the industry,” Glover said, no pun intended.

To have a Texas Tech alumnus be part of the writing process is a point of immense pride for the professor.

“Ms. Beals is an exceptional example for our students,” Glover said. “Through her life experiences, students can see themselves and plot their futures in the jewelry design and metalsmithing field.

“Alumni connections are seldom considered when starting a young career; but in some instances, they’re everything. Ms. Beals has taken the time following her visit to mentor many of our students. I am extremely grateful for her diligence to Texas Tech students.”

The GIA curriculum revamp came during the later stages of COVID-19. The faculty paused classes and took time to rewrite texts. Eight faculty instructors were asked to be on the team of writers from GIA’s dozens of faculty members.

New components of the curriculum include various aspects of fabricating jewelry from raw materials, engraving, laser welding, carving wax and casting.

Catching Light

Beals has learned nothing is certain; like the gems she works with, there are imperfections. She’s also learned to make the most of the materials she’s been given.

“I shouldn’t be walking right now,” she said. “That changes your perspective. I get to go for a walk, it’s not something I have to do. I feel a lot of gratitude for that.”

And never in her wildest dreams when she was grading papers at Texas Tech did she imagine contributing to the very textbooks she admired.

She says life can surprise you like that.

One of her favorite pieces of personal jewelry is a ring she rescued. She shows it off as she extends her hand, allowing a few small diamonds to catch the light.

“I was working at a jewelry store back in Tennessee when someone brought this in to sell the gold,” she said. “My boss was going to melt it down, but it caught my eye, and I rescued it from the scrap heap.”

Beals couldn’t take her eye off the hidden beauty of the simple band.

“That’s the human experience,” she said. “It’s beautiful and difficult at the same time.”

And according to Beals, when that juxtaposition is captured in a piece of jewelry, that’s when you get something spectacular.