Sue Yang implemented fNIRS technology in a recent neuroaccounting study analyzing functional diversity’s impact on creativity in teams.

“Accounting” brings to mind many things. Excel spreadsheets with lines of various dollar amounts and complex formulas. Isolated, sometimes stressful workspaces housed in cubicles. Articles or academic papers featuring complicated or confusing tax codes.

Sue Yang, assistant professor of accounting at the Jerry S. Rawls College of Business at Texas Tech University, is hoping people’s understanding of accounting will soon expand.

“It’s more like we are the designer of a company,” Yang said about her field of managerial accounting. “We design the incentives, the contracts and the management control systems. If it was just about numbers, I never would have become an accountant.”

Yang sees accounting in the modern business world as extending well beyond traditional financial reporting. It influences every aspect of a business, from bookkeeping to strategic decision-making.

Her work is part of a new interdisciplinary field of study called neuroaccounting that combines neuroscience, cognitive science and managerial accounting. Yang hopes to utilize different neuroimaging technologies to better understand how and why various workplace managerial decisions impact people in certain ways.

While neuroimaging technology and accounting research may seem like an odd combination, to Yang it was a natural progression of her life’s work.

Not a Typical Accountant

Before beginning her accounting career, Yang initially started in the medical field. She felt the weight of being an only child, carrying the hopes and dreams of her parents.

“They wanted me to become a doctor,” Yang remembered, “but I wanted to be in business since my mom ran her own business.”

Yang ceded to her parents’ wishes and attended medical school in Beijing. She eventually would move to the U.S to work toward her doctorate degree in biomedicine. However, nearly two years into her program, Yang was facing an identity conflict.

“I was doing animal experiments, but the whole time I hated it,” Yang said. “I love animals, but my job was hurting them.”

Yang left her program with her master’s degree and turned her attention back to her interest in business. It was the adage “accounting is the language of business” that inspired her to study accounting and earn her master’s degree.

Yang deviated from many of her fellow students when graduation came. She received multiple offers, some even from Big Four firms like Ernst & Young. However, she wanted work that utilized her medical background and took a position with Stryker, a medical equipment manufacturing company. After 10 years of working as part of different functional teams within the company, Yang still felt as if something was missing.

“I remembered my initial purpose in coming to the U.S. was to finish my doctoral training,” Yang recalled. “I still wanted to fulfill that part of my dream.”

While earning her doctorate in accounting from Michigan State University, Yang finally fell in love with doing experiments, this time within the social science of business. She needed to find a way to merge her science background with her burgeoning accounting research.

Yang jumped at the opportunity to join the accounting faculty at Rawls College because of the access to neuroimaging technology, something she didn’t see at other business colleges across the country. A mere minutes’ walk from Yang’s office is the Texas Tech Neuroimaging Institute (TTNI), home to a state-of-the-art facility that provides researchers access to brain- and body-imaging technologies like magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), functional MRI (fMRI) and diffusion tensor imaging.

“The biggest hurdle for accounting or business researchers to use neuroimaging technologies is the lack of connections,” Yang said. “The equipment is normally in a medical school or psychology department, so we first need to generate those connections and seek approval. The Neuroimaging Institute basically removes those hurdles.”

It also helps that the current director of the TTNI is Eric Walden, the Jerry S. Rawls Chair of Information Systems & Quantitative Sciences. Knowing the director is in such proximity – both academically and physically – Yang doesn’t have to sell the need for neuroimaging technology in accounting research. Instead, she can lean on Walden’s expertise in business and neuroimaging to help design her experiments.

Yang also appreciated having access to the smaller neurological technology lab in the basement of Rawls College, where she could use more fundamental technologies like eye- and face-tracking programs.

Yang had found her ideal environment that melded neuroscience and accounting. She was ready to get to work.

Functional Diversity’s Impact on Creativity

Yang, along with her co-researchers, recently published a study in the journal “Management Science” that examines how a team’s composition can impact its creativity. Would a team that was more functionally diverse – think people from different departments within a company – have greater creativity than a team whose members were all from the same area?

The origin of Yang’s research question came during the COVID-19 pandemic. She and her husband, like many people at the time, were working from home. Yang’s husband was a research and development manager for a company where he often was in brainstorming meetings for new products. She remembers him occasionally ending video calls, exasperated at the lack of progress. He would sometimes question why some people from certain departments like legal or marketing were invited to the meeting.

“He thought the talks would slow down because the people couldn’t communicate well,” Yang recalled. “I was seeing this conflict happen and getting the information from a practitioner. I wanted to know, well, does a team’s composition actually help the team’s creativity? And if so, how?”

Yang decided to focus on functional diversity of a team’s makeup because it’s often one of the ways managers decide who to invite to meetings.

Working with a university in China, Yang and her co-researchers created teams of two students. The functionally diverse teams featured one student from the business school and another student from the engineering school. The functionally homogenous teams were composed of students from the same school.

The goal was to broadly emulate the two core areas of a company. Engineering students represented the group of professionals who would help research and design a product, and business students represented the group who would sell and market a completed product.

Student teams were tasked with creating a proposal for an empty office space on campus. The proposals were then evaluated based on their overall creativity.

Early on, Yang was surprised to see little variance in the creativity scores between functionally diverse and homogenous teams. This went against what current researchers were saying, that more diverse teams should be more creative.

Yang realized the experiment needed more precision with its definition of creativity to better understand what was really happening.

“When we talk about creativity, we often talk about overall creativity, but there are actually at least two basic dimensions: uniqueness and usefulness,” Yang said.

Yang and her co-researchers tweaked the experiment and had evaluators rate student proposals based on uniqueness and usefulness, not just overall creativity.

“We received one proposal for an escape room,” Yang recalled, laughing. “It’s very creative, right? But it’s not very practical for a building on campus. This type of proposal had high uniqueness but low usefulness.”

Now, some clear variance was becoming more noticeable. Functionally diverse teams had higher unique creativity scores while functionally homogenous teams had higher usefulness creativity scores.

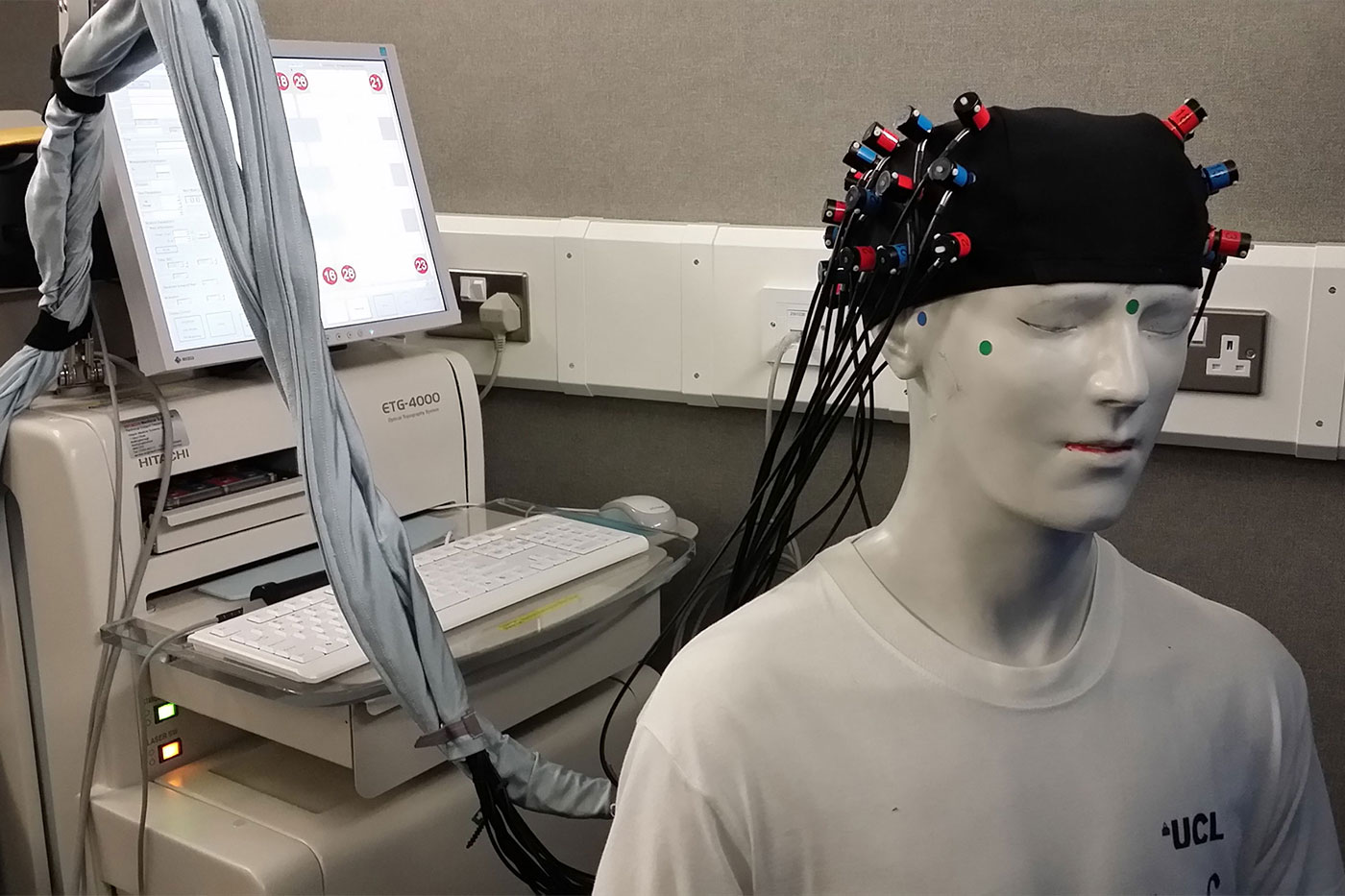

Yang and her co-researchers also ran the experiment using a functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) device to measure the brain activity of the students as they completed the task. According to Yang, this is the first accounting or business study to implement this technology in a team environment.

Students wore special helmets that measured brain activity by analyzing changes in blood oxygenation levels. Yang and her co-researchers wanted to see how students’ brains synchronized during the task. The cognitive data seemed to track with the behavioral evaluation results.

“Functional diversity can stimulate or motivate divergent thinking in our brain,” Yang said. “But it can also decrease the convergent thinking. Divergent thinking is critical to those novel ideas, but convergent thinking is needed to generate useful, implementable ideas.”

Practical Implications

Yang sees her work as opening a black box and providing immediate implications for managers today. They need to be willing to adjust their designing of a team to maximize potential success.

“If a manager wants the team to innovate, they should focus on functional diversity,” Yang said. “If they want the team to implement, they should focus on homogenous teams.”

Yang is continuing to bring neuroimaging technologies into accounting research with her current study that uses an fMRI device to understand how people respond to different types of managers (human versus artificial intelligence).

She’s excited for the future of neuroaccounting and believes that Texas Tech could be at the forefront of this discipline.

“Accountants are not famous for trying new things,” Yang joked. “I hadn’t met many accountant researchers that were passionate about exploring new areas together with me. But when I came here, I met several colleagues who offered intellectual support. We have everything at the ready to make this research possible.”