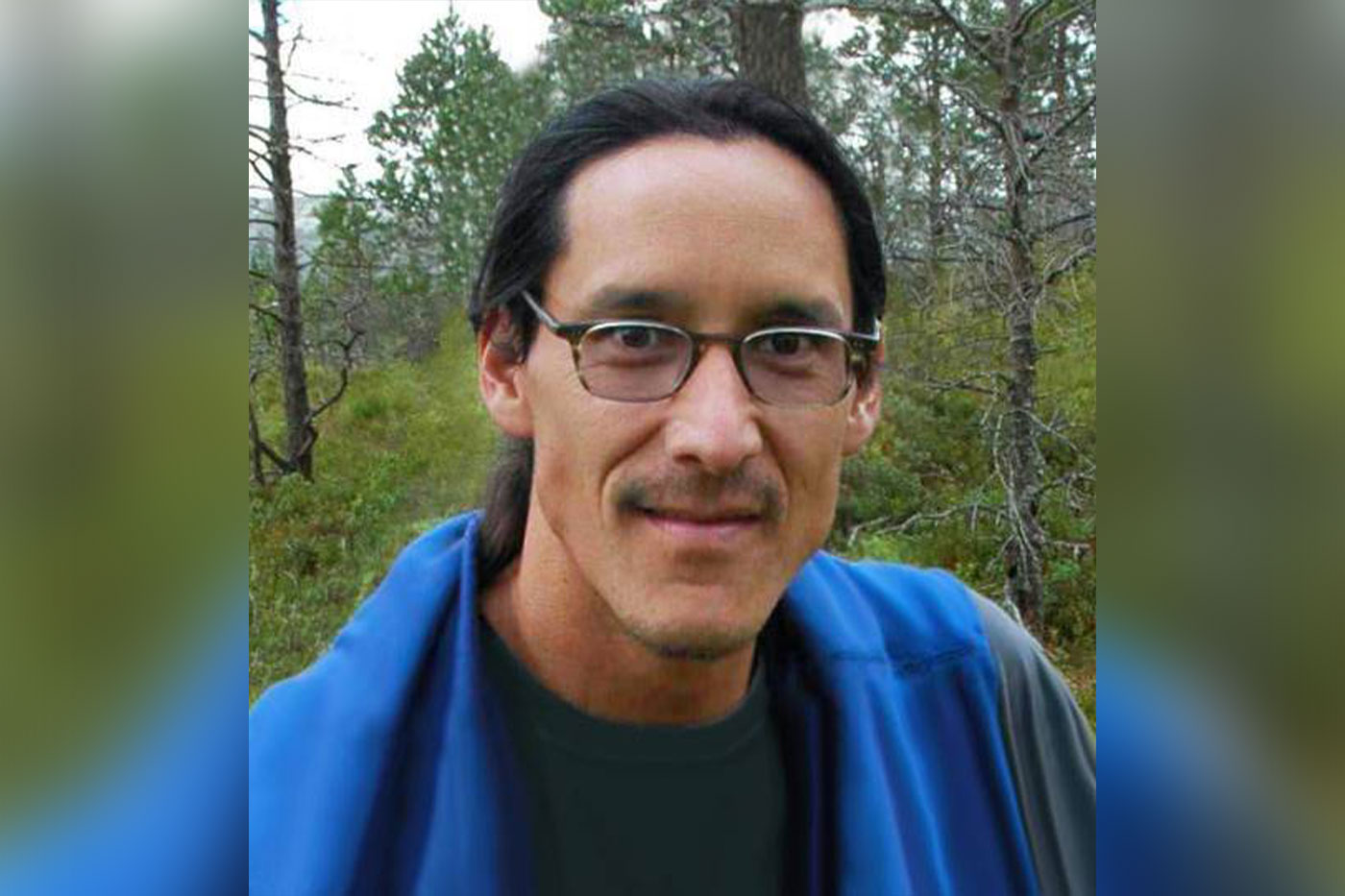

In addition to teaching Texas Tech students structural geology and tectonics, Aaron Yoshinobu has stayed busy helping maintain the legacy of an environmentalist icon.

“I gazing at the boundaries of granite and spray, the established

sea-marks, felt behind me

Mountain and plain, the immense breadth of the continent, before

me the mass and doubled stretch of water.”

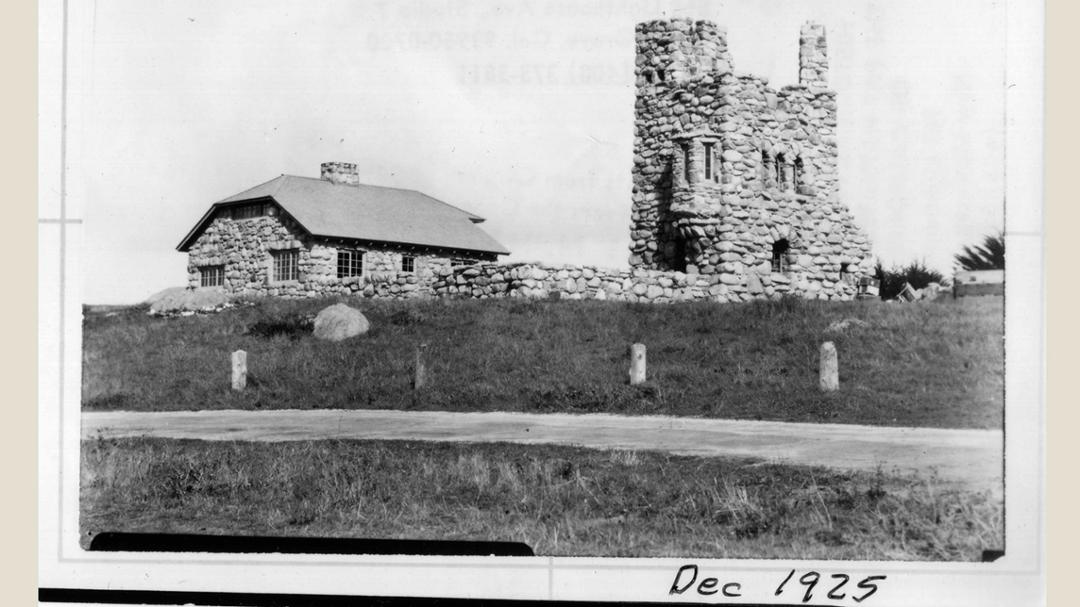

Any visitor, past and future, to Tor House and Hawk Tower in Carmel-By-The-Sea, California, can visualize the words from famous poet Robinson Jeffers’ breakthrough work written just over a century ago.

“Continent’s End” (1924) characterizes Jeffers’ connection to nature while he stands on Carmel Point, a location that feels like the edge of the earth. Far away from the stories of European migration to North America, one of the final stops in the United States’ westward expansion, and isolated from humans’ sometimes destructive nature.

Aaron Yoshinobu, a Texas Tech University professor in the Department of Geosciences, says he experiences the same lifelong feeling Jeffers did when he touches the coarse granite comprising the stone house and tower and looks out at the water.

The sentiment works like love, in that life introduces ups and downs, moments of jubilation and despair, but through all that, what matters is love experienced between friends and family.

“When touching the earth at Tor House, when working with the rocks, Jeffers could sense that longevity and that connection with something that’s eternal,” Yoshinobu said.

Through over a quarter century in Lubbock, Yoshinobu has pursued interdisciplinary research of Jeffers’ impact on the arts and geology several times. His latest sabbatical in fall 2024 left Yoshinobu rejuvenated for the spring 2025 semester, ready to take what he learned and share it with colleagues, students, friends and more.

He’s also carved out a work-life balance that’s allowed him to serve on the Tor House Foundation’s Board of Trustees and as the now former president of the Robinson Jeffers Association.

His activity maintaining Jeffers’ legacy is poised to see a spike, after the U.S. Secretary of the Interior designated the Tor House among 19 new National Historic Landmarks in December 2024.

Dedicating so much time to interdisciplinary research outside his immediate responsibilities at Texas Tech has re-energized Yoshinobu, with that aspect being one of many reasons he’s stayed in Lubbock so long.

Early Exposure

Growing up just seven miles from Tor House in Pacific Grove, Yoshinobu’s childhood was greatly influenced by Jeffers’ legacy.

His mother was particularly struck by Jeffers’ philosophy of inhumanism, the attitude criticizing humans for their focus on power dynamics that can be found in capitalism, politics, war and so on, breeding human suffering, which also emphasized focusing on Earth’s natural beauty. She and Yoshinobu’s father led their family into nature often, in addition to sharing philosophy and poetry.

Yoshinobu’s memories include walks by the water, visiting the Big Sur area and hunting for jade stones at Jade, backpacking the Ventana Wilderness and more.

He also spent plenty of time outside with his friends, frequently walking the few blocks down to the beach and enjoying bonfires. Even then, Yoshinobu felt separated from all of civilization and humanity on the shore of the Pacific.

His connection with nature lingered as he went off to college, though years passed before Yoshinobu knew geology would be his future.

Midway through his six-year college experience, Yoshinobu called his mother in tears, dejected and depressed after repeatedly switching majors with no solution in sight. His mother suggested he try geology, and during the next semester, a chance geology field trip to the California desert changed his outlook forever.

Yoshinobu hasn’t looked back since, and it’s all thanks to his mother’s intuition.

“I think she knew she and I had this tendency toward wanting to be alone in nature, sitting on a rock and meditating in the sea breeze or watching the pelicans fly,” he said. “There’s something that’s very peaceful and redeeming about that for me, and she definitely had that in her, so she was giving that to me.”

The seminal moment that forever tied Yoshinobu to Jeffers’ work occurred in summer 1997.

Yoshinobu was somewhere in the Klamath Mountains that span California and Oregon, camping while conducting graduate school research. Part of his daily routine included reading a long narrative of Jeffers’ called “Cawdor,” a story modeled off the Greek tragedy “Hippolytus” but set in Big Sur.

Within “Cawdor” is a scene where an earthquake happens, causing the ocean to sink, mountains to rise and the earth to shudder, depicted eloquently prior to the introduction of the theory of subduction scientists would generate in the 1960s.

Subduction is when continental and oceanic plates collide and the oceanic plate goes underneath, which can cause earthquakes, tsunamis and volcanoes.

“One of the things that grabbed me when I first read this was the thought of ‘Oh my gosh, he’s describing things I’m learning about,’ Yoshinobu said. “But he was thinking this on his own in 1927.”

Upon earning his doctorate from the University of Southern California in 1999, he immediately started work at Texas Tech. With an understanding of Jeffers’ influence on art and science, Yoshinobu began attending conferences held by the Robinson Jeffers Association, using sabbaticals to dive deeper into the intersection between Jeffers’ geology and poetics.

The Formation

Tor House and Hawk Tower are in what is now the affluent neighborhood of Carmel Point, on property Jeffers’ purchased for $1,900 – roughly $35,000 today – in 1919.

At that time, Jeffers was still an unknown poet, but as he began construction and gained intimate knowledge of the property’s stonemasonry, Jeffers found the style that would boost him to fame.

Construction included rolling immense, coarse-grained granodiorite stones (often referred to as granite) up from a quarry located 50 feet below Jeffers’ plot and placing them by pushing the rocks onto pyramid-like scaffolding or using a block and tackle pulley system.

As Jeffers progressed in this endeavor, his poetry evolved to a free verse style linked to the ages of the rocks he worked with.

“He came to understand the rhythmic nature of the earth, and his work took him out of the human timescale,” said Yoshinobu. “His poetry toggled between the human scale of putting a stone in a wall to the astronomical scale of galaxies growing and dying.”

Jeffers’ publication of the collection “Roan Stallion, Tamar and Other Poems” in 1925, which included “Continent’s End” – also included in a contemporary collection of notable California poets’ work – helped launch his stardom on a soaring trajectory.

He appeared on the cover of TIME Magazine in 1932, had the milestone book “The Selected Poetry of Robinson Jeffers” published by Random House in 1938 and participated in a reading tour at the Library of Congress in 1941. Jeffers was a trailblazer in what would become the environmentalist movement in science in the ‘60s, after his death in 1962.

His emphasis on the beauty of the natural world, the smallness of human existence and the connections between those two realities had a significant impact, Yoshinobu said.

“Because Jeffers talked about geology and astronomy, I have a number of colleagues in both of those fields who are familiar with Jeffers,” Yoshinobu continued. “It’s clear, the reasons why scientists tend to gravitate toward his work.”

Entrancement

Yoshinobu describes the Tor House property as one of the most beautiful places on Earth.

“When you enter the gate, you see the tower and you see the house, and then beyond that the Pacific Ocean, it’s almost like you get these blinders on and you don’t see the rest of the world,” Yoshinobu said.

“It’s like immersing yourself into a world that’s primordial.”

Past the main and inner gates, the volume of the water roars, making Yoshinobu giddy.

During his most recent sabbatical, he’d arrive early in the morning before property staff and visitors and stay well after closing time.

“I’d lock things up, I’d climb up the top of the tower and I’d just stand there on the parapet and look out at the Pacific,” Yoshinobu said. “Hearing the thundering surf, the squawking of seagulls, the breeze through the cypress trees, and I just felt a real sense of peace.”

As his mother knew many years ago, Yoshinobu extracts that same enjoyment from observing and seeking to understand the formation of landscapes. Studying the Llano Estacado caprock was crucial to his forming an appreciation of Lubbock’s history and people in a place so different from the California coast.

Geology provides answers to questions about Earth’s evolution, mineral resource distribution and the hazards of earthquakes, landslides and volcanism, all subjects that scratch the itch of the self-described wannabe historian. Now, Yoshinobu’s playground for exploring these topics extends from the Southern High Plains to the mountains of New Mexico and Colorado, where he leads classes on developing analysis in the field.

When he came back from his sabbatical, he realized the saying that when people leave Lubbock, they end up missing it, held true for him, too. Living in Lubbock is simple, Yoshinobu said.

“I don’t even have to drive; I ride my bike to work every day,” he added. “There's a brew pub down the street. There's a coffee house down the street. There's a grocery store down the street. So, it's like the ideal life.”

Occasionally before a class starts, Yoshinobu displays a poem of Jeffers’ on a PowerPoint slide.

As students enter the room, the class will have a few minutes for people to discuss their thoughts of that day’s piece.

It’s a routine, almost overlooked part of every session. But those poems’ inclusions mean a lot to Yoshinobu, an extension of the freedom he possesses to participate in interdisciplinary research and service.

The abundance of energy, opportunities and space the Texas Tech administration supplies is another positive. Having watched his former colleague Lawrence Schovanec become president, Yoshinobu feels the university is on a great path, spearheaded by someone who understands its history and the intricacies necessary to advance it.

Texas Tech has created an environment that makes many things possible and allows faculty to follow their natural curiosity wherever it leads them.

“There are a number of us who feel very fortunate because we have a job where we can really pursue things that are interesting to us, teach those things to students who then become interested in it, and engage with it,” Yoshinobu said.

“It’s pretty rare.”