Jeff Wilde took what he learned as an engineering physics student and parlayed it into a successful career as an entrepreneur and teacher.

It isn’t like Jeff Wilde saw himself spending his entire career in California. It’s just the way life worked out.

And he would be the first to tell you it has all been for the best. Sometimes, as the band Steely Dan once sang, there is something to be said for reeling in the years and stowing away the time.

These days, Jeff is a successful Bay Area consultant who also is an adjunct electrical engineering instructor at Stanford University. He is at a point in his career where he can pick the clients and projects he wants to be a part of while staying involved in the lives of his three children.

It’s a long way from Lubbock, Texas, to Los Altos, California, a Bay Area suburb neatly nestled between San Jose and San Francisco – in more than one way. Once Wilde settled in with job, wife and family, there really was no reason to go anywhere else.

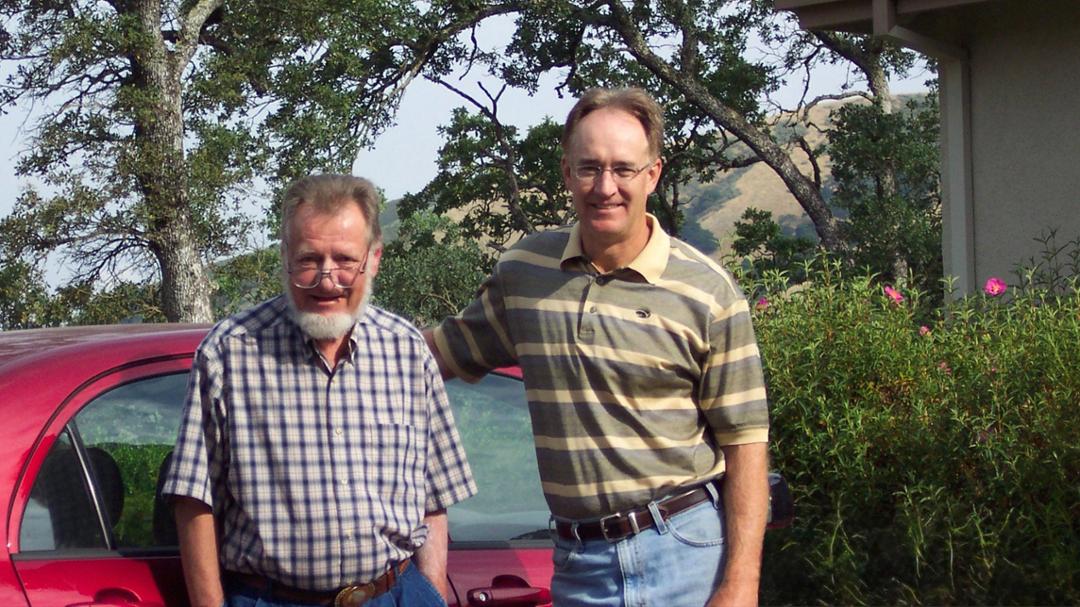

Wilde grew up in Lubbock, graduating from Coronado High School and deciding to attend Texas Tech University, where his father taught in the Department of Chemistry & Biochemistry for 32 years. His brother, Vince Wilde, a project/senior engineer, has been a longtime fixture in the department as well prior to retiring this semester.

“Coming out of high school, I knew I wanted to study either engineering or physics,” Jeff said. “On College Night at Coronado, Texas Tech was the only school that offered engineering physics, so it was a natural choice.”

It was also something of a unique degree plan at the time. The curriculum required students to select an engineering discipline that would comprise one large block of classes with another chunk composed of physics classes. Sprinkle in a lot of advanced math, and you had the makings of a challenging academic path.

Jeff picked electrical engineering, hunkered down and went to work.

“It was unique, and it was perfect,” he said, “and it was exactly what I was looking for.”

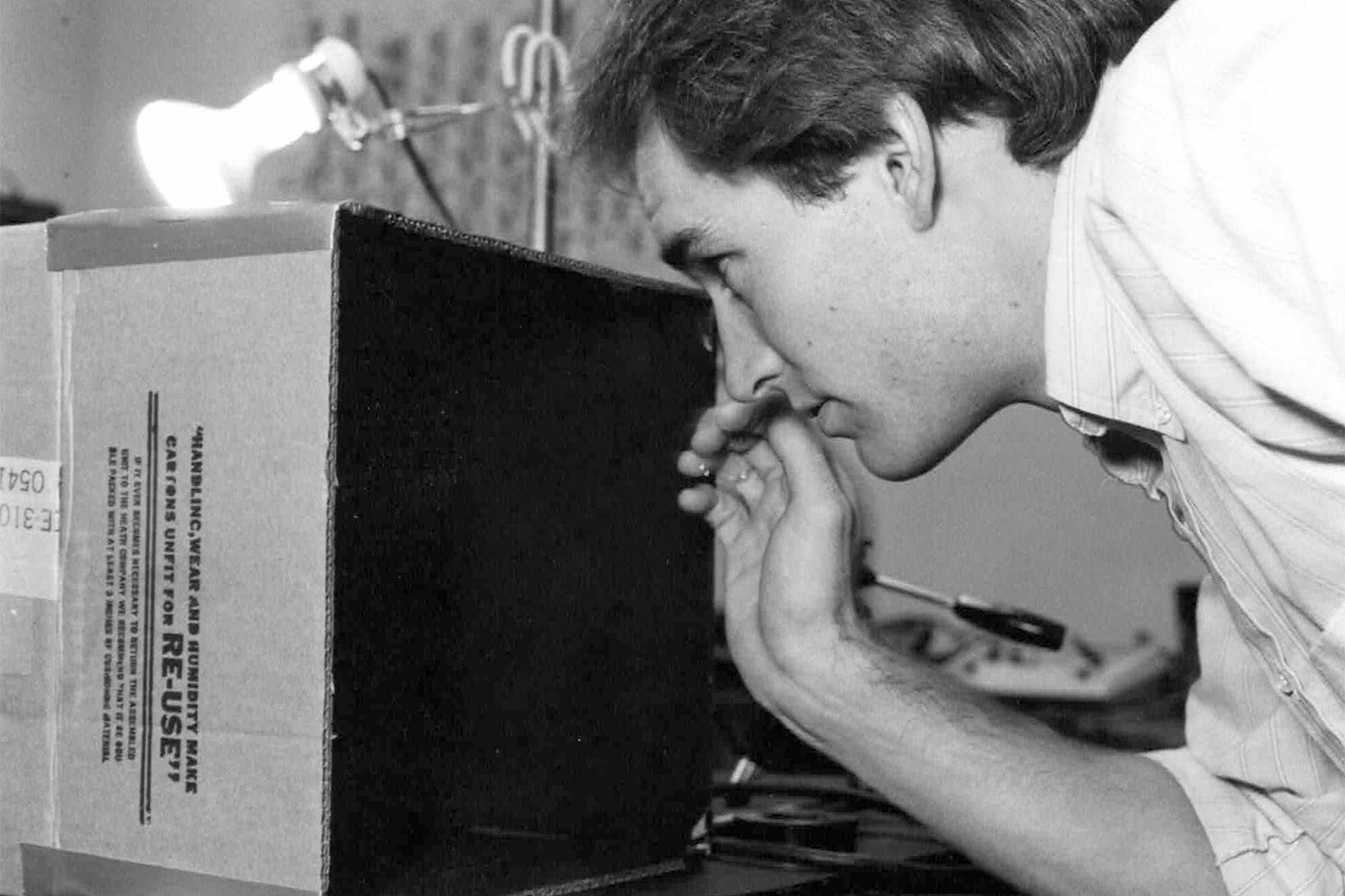

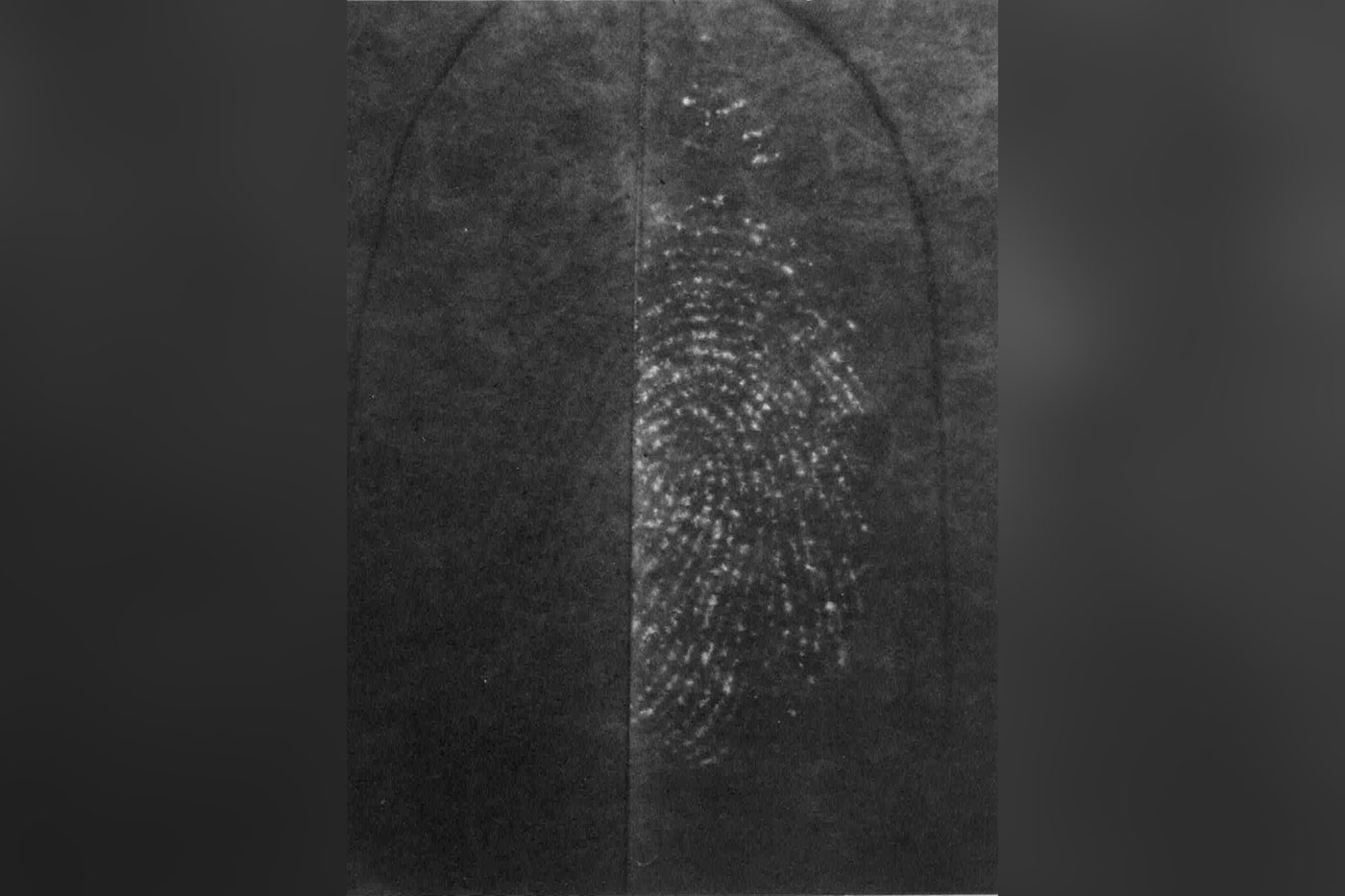

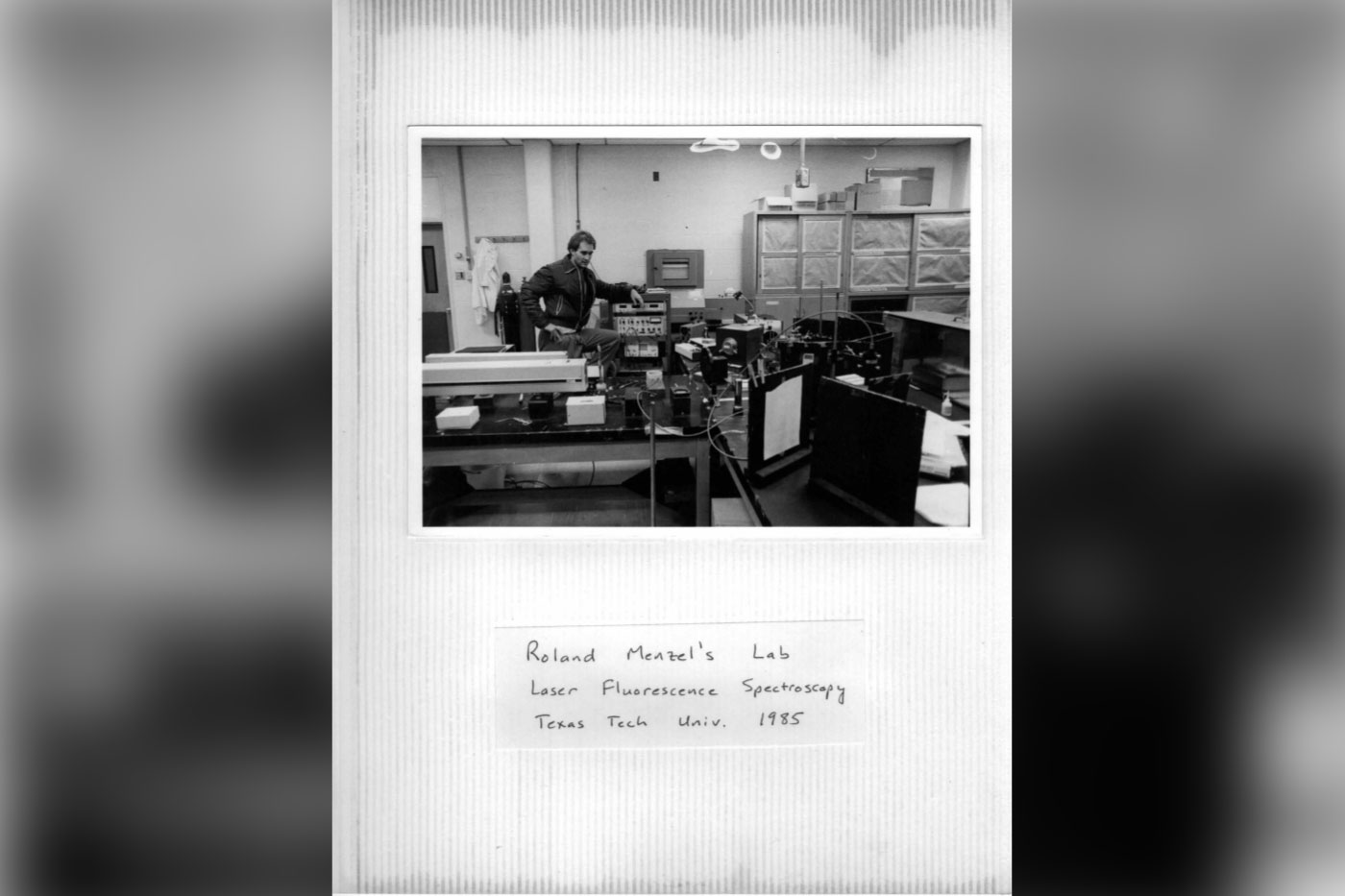

At Texas Tech he connected with legendary professor Roland Menzel, a brilliant physicist who invented laser fingerprint technology. Menzel, who died in 2006, was named a Horn Distinguished Professor of Physics in 1997. He became a mentor to Jeff, providing him with opportunities to assist with research in his laser lab.

Looking back, Jeff sees that door opening as one of many serendipitous moments in his life. He was walking to class one day when a notice on a bulletin board in the Science Building caught his attention. Menzel had just landed a grant and was looking for a couple of undergraduate students to help.

“That was a little bit unusual,” Jeff said. “Not only at Texas Tech, but at most schools. Usually, they want to hire graduate students to work in the lab and do the research.”

Jeff wasted no time booking an appointment with Menzel. He asked about the research that would be conducted, found it interesting and was hired in short order.

He still remembers one of the key rules of working in Menzel’s lab. It wasn’t a cavalier approach, but Menzel insisted his assistants take to their work with an air of fearlessness.

Otherwise, they might never discover what was possible.

“He taught me a lot about just going for it,” Jeff remembered. “There’s a rule he told me that I’ve never forgotten. He said, ‘Jeff, I want you in the lab. If you go in there and you break an expensive piece of equipment, I will not be mad at you for trying. However, if you don’t go in the lab and you don’t try anything, I will be very upset.’

“And he had a lot of expensive equipment, so it was a little bit intimidating. It was permission to tinker, explore and not be worried about failure.”

As you might imagine, Jeff not only spent time in the lab then, but it’s also where he has comfortably spent his time in the decades since.

He also worked as an intern for Texas Instruments and helped teach physics labs. Those experiences, along with immersing himself in more advanced physics classes, convinced him to pursue graduate school.

That is how he wound up in California, but Jeff doesn’t underestimate the role Texas Tech played in his address change.

“Texas Tech definitely provided a lot of unique opportunities to allow me to get to a place like Stanford,” he said. “That wasn’t the plan going in. I just enjoyed what I was doing when I was a student at Texas Tech. I was there five years because there were just so many courses and so many things I wanted to learn. I couldn’t fit it all into four years.”

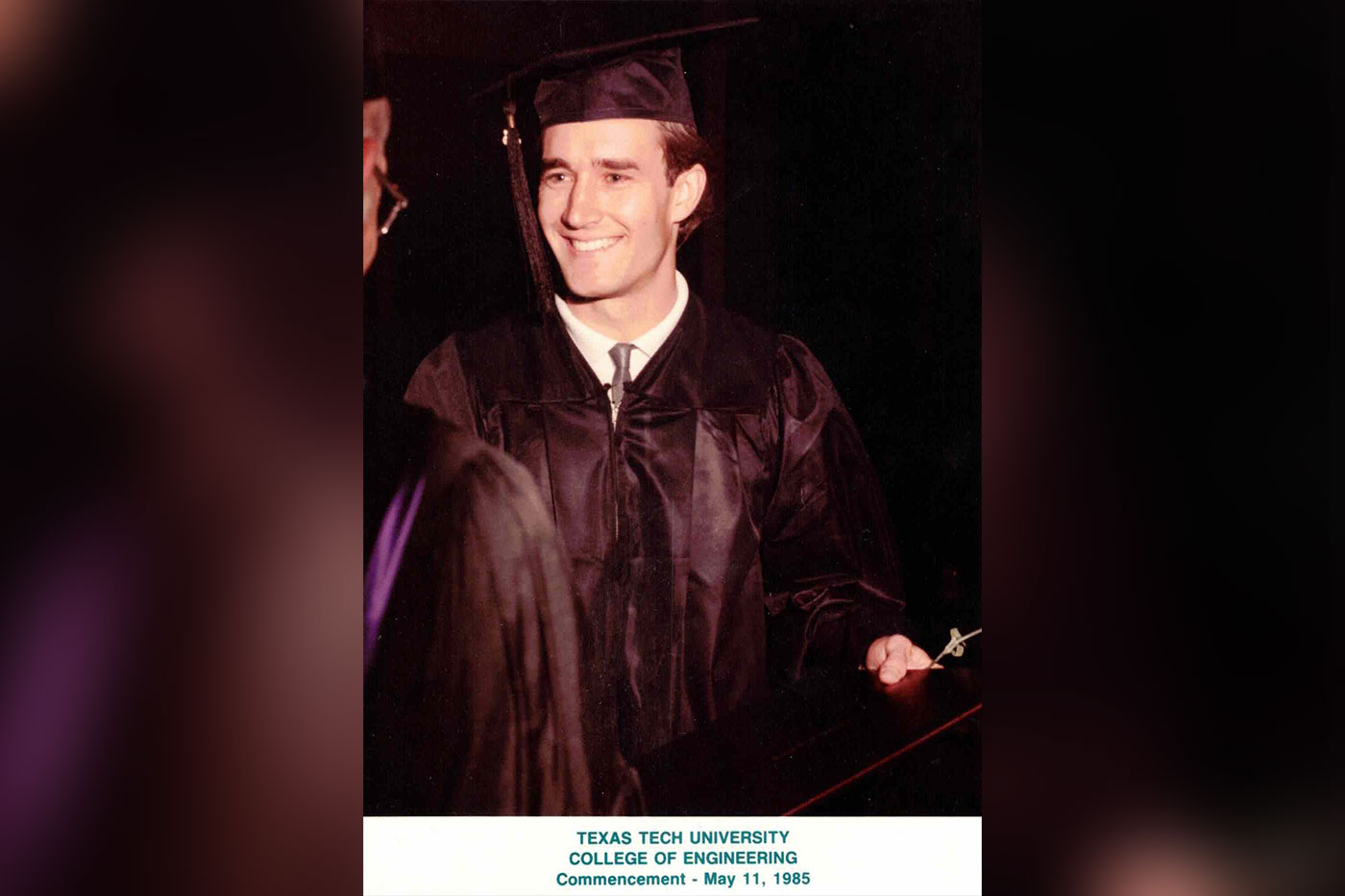

Jeff completed work on his undergraduate degree in 1985. He applied to a handful of graduate schools and was accepted at Stanford. It was something of a transition, leaving the comfort and familiarity of West Texas, but Jeff believed it was just what he needed to grow.

He remembers that first year of graduate school being extremely difficult, but he made connections and focused on what was in front of him: attending lectures, meeting assignment deadlines and working as part of a small study group.

“The Stanford environment was (and still is) very competitive,” he said. “You really have to work on staying in a positive frame of mind, even if you feel inadequate. As time went on, though, I became more comfortable.”

The challenging academic setting was just what Jeff needed. He went on to earn his doctorate in applied physics.

“Jeff’s blend of down-home Texan charm and consideration with top-level technical expertise and analytic rigor has made him successful in both business and research,” said Murray Reed, who met Jeff when the two were just beginning graduate work at Stanford. “He is always a pleasure to be around.”

Along the way, Jeff also narrowed his focus area to optics, which he explained as the science and technology of light. His interest was kindled while working in Menzel’s laser lab. He wanted to know more about it.

“I wanted to explore how it works and how you model it, how you treat it mathematically,” he said. “It started out as pure curiosity. I wanted a fundamental understanding of what exactly light is, and yes, there are a lot of layers to that answer.”

He has invested a great deal of his career into understanding the intricacies and the possibilities of light, peeling back its layers and digging in to what new knowledge might be uncovered. Over the years, Jeff has had 31 journal publications and 39 U.S. patents issued. He also is a senior member of the Optical Society of America, now Optica.

Originally, he saw his time in the Bay Area as a chapter of his life, one he would eventually turn the page on. He thought he would earn his master’s and doctoral degrees and then move back to Texas, expecting to settle in the Austin area, where the entrepreneurial spirit was alive and well thanks in part to a tech sector that was continuing to blossom.

However, those plans were interrupted. Initially, a recession in the early 1990s had an especially significant impact on the Bay Area’s tech industries. Jeff’s plans to land a position with an industrial research lab were scuttled, but nowhere is entrepreneurship more appreciated than Silicon Valley.

Despite the economic headwinds blowing against him in those early days, Jeff decided to strike out on his own. He started a small company and soon secured grant funding that allowed him to rent office and lab space.

He also began networking and soon connected with a group of high-tech disk-drive industry veterans to start a new data storage company, Quinta Corporation, which they sold in 1997 to Seagate Technology, a major disk-drive corporation. A few years later, he helped start Capella Photonics, a manufacturer of wavelength switching products for the telecommunications industry.

That company was acquired by Alcatel-Lucent, now Nokia, in 2013.

Those two deals, as well as a legacy of accomplishment, cemented Jeff’s reputation as a brilliant problem solver and gave him relational capital in one of the most innovative places in the world. Since then, he has used his talents to help recognizable companies like Intel and Illumina resolve challenges and increase operational efficiencies.

For Jeff, though, it wasn’t only about professional fulfillment. He learned long ago there was more to life than a successful career.

“Life is too short not to consciously focus on a balance,” he said. “After starting two companies, I decided to take time off. I learned how to play golf and, in the process, made some great lifelong friends. I also started a consulting business. I came to realize I truly love learning, so I stick with consulting and actively engage in academic pursuits. It’s been a nice balance.”

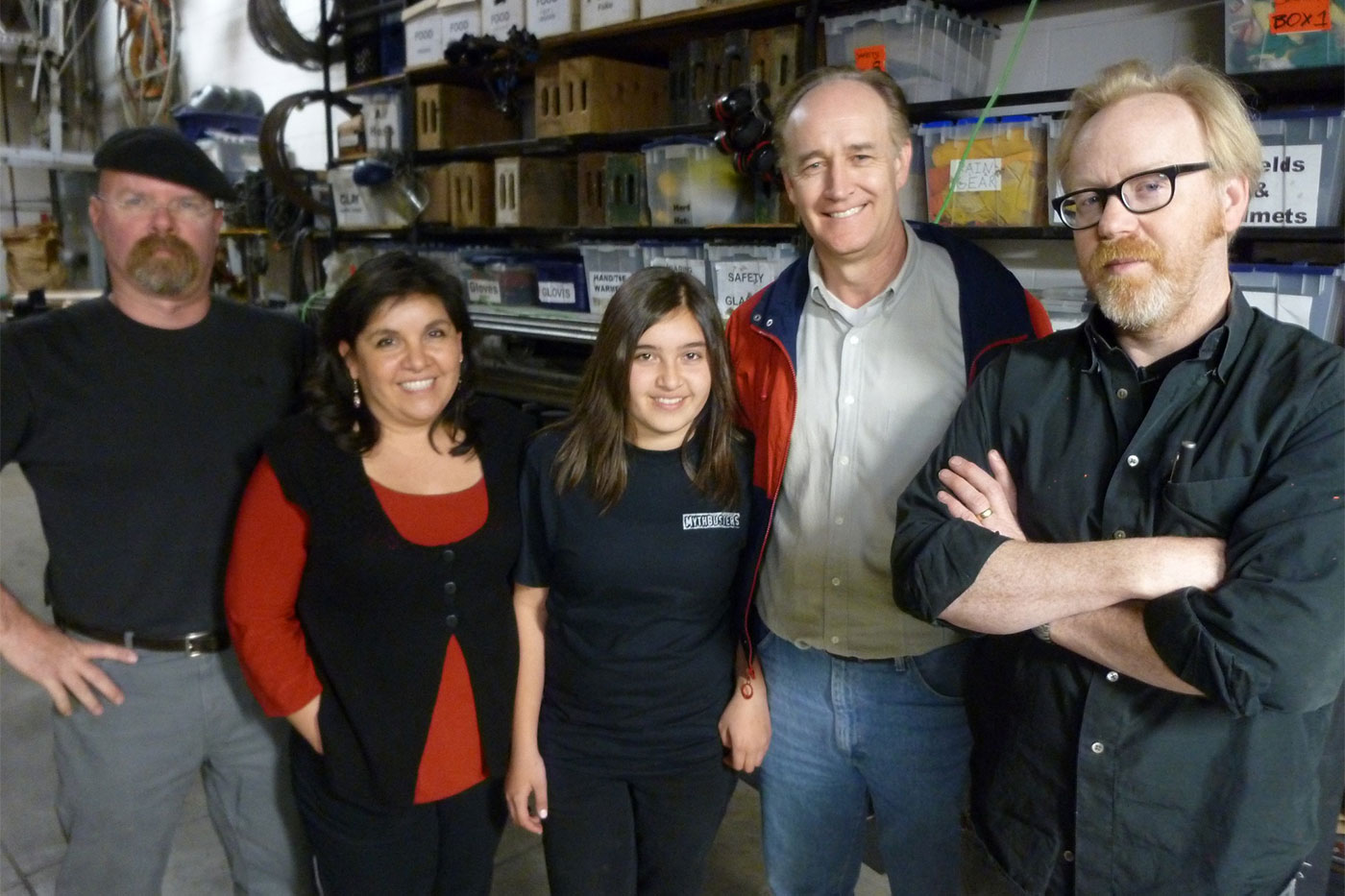

For most of the past 20 years, Jeff has provided optical design consulting services to several companies, including an opportunity to provide technical guidance for an episode of “MythBusters.” He also has served as a research consultant with Ginzton Laboratory at Stanford, working on projects in fiber optic communications and advanced imaging technologies.

“It’s very rewarding,” he said. “On the commercial side, I basically come into these companies and work as part of a team. I am more of a senior technologist within their team. They bring me in because they don’t have a certain skill set internally, and they don’t necessarily want to go out and hire. They prefer to bring somebody in with experience so they can get going right away.”

In addition to working with Intel and Illumina, he also has provided expertise to over 30 companies in a variety of sectors, including health care, telecommunications, semiconductor equipment and industrial optical sensing.

“The first thing I think about is if my background is a good fit for the client,” he said. “I want to be able to make a meaningful difference. If I think I’m a good fit, I tell them. If I don’t think I am, I let them know that as well. I also need to think that I can enjoy working as part of their team.”

That often involves an informal interviewing process, perhaps over lunch, with the core members of the team he’s going to work with. Typically, that gives him a good idea of the team’s chemistry and how effective he can be.

“I recall one of the projects Jeff partnered with me on,” said Hod Finkelstein, who has known Jeff for about 14 years. “This was another ‘crazy’ project, which initially seemed impossible. Indeed, after hearing the details, Jeff politely smiled and explained which foundational physics principles would be broken if we took the proposed approach. This drove us to rethink our solution, and only once we received Jeff’s blessing, we moved forward with designing the novel module.”

Jeff also enjoys teaching, seeing it as a way to give back and grow at the same time. At Stanford, he partners with his former doctoral advisor, professor Lambertus Hesselink, to co-teach two optics classes in the electrical engineering curriculum. The way it works out, his professional life roughly breaks down over the long term to half commercial technology development and half academic pursuits.

“Jeff is a great friend and collaborator,” said Hesselink, who first met Jeff when he began pursuing his applied physics doctorate in 1986. “Co-teaching with Jeff has been part of a continuing learning experience for me. He is a wonderful member of the cohort of former students, many of whom are lifelong friends. I like to thank him for his friendship, for his contributions to our research and teaching effort, for teaching me (and contemporary students in the group) water skiing and for the trips we made together to the Sierra mountains.”

Teaching and consulting represent a perfect blend for Jeff, allowing him time to focus on other priorities.

“Now that I have a family with three children, I have purposefully structured my life so I can largely determine my own schedule,” he said. “Making time to go to my children’s events is very important. I realize that if you miss out, there’s no second chance, so I have enjoyed watching my children grow up.”

Similarly, he likes being in the classroom and seeing students not only catch principles but also on occasion teach him.

“I actually learn quite a lot too,” he said. “It’s been a very interesting experience. These are some of the best students around, so you can’t cut corners or say something or do something that’s not quite right because it doesn’t take long for them to point that out. Teaching, along with academic research, really helps me stay current.”

Jeff has never forgotten the impact Texas Tech in general and Roland Menzel in particular made on his life, and his professional accomplishments have given him occasion to give back to the university where it all started.

As a result, he has contributed $100,000 to a scholarship fund in Menzel’s name that was established in 2006 and is specifically aimed at supporting undergraduate students who will participate in research opportunities – much like he did. For Jeff, who plans additional gifts to the fund in the future, this is also a way to connect his philanthropic passion to Texas Tech’s On&On priorities of fueling academic excellence and transforming lives.

“Dr. Menzel was very instrumental in getting my mindset and experience established so that I could go on to graduate school,” he said. “For me, it’s an opportunity to help undergraduates as opposed to graduate students because there seems to be a lot more funding support available for grad students compared to undergraduates.”

His passion for learning and for sharing his knowledge with others comes through no matter what setting Jeff might find himself in.

“Jeff is an inspiring engineer and physicist with a wonderful, kind personality,” said Hesselink. “He is always concerned about the well-being of students, friends and faculty alike.”

For Jeff, investing in the Menzel scholarship is a concrete way to help more students find their way into science and physics and a constellation of extremely rewarding career possibilities.

“I would tell students today to study hard and make the most of your educational opportunities because that will help you launch a career,” he said. “If you are lucky, you wake up every morning looking forward to what the day brings, and a positive attitude is infectious.

“Do what you love, do it well with pride of ownership in your work product, be honest and remain humble.”

Wherever you are. Wherever life takes you. And however long you might be there.