A scientist, a soldier and an athlete walked into a university – and it was never the same. No joke.

Tomasa Cavazos gazed intently into her eldest son’s eyes. He was a man now – she couldn’t stop him even if she wanted to, and a part of her wanted to. But in those steady brown eyes, she saw how much he wanted her permission and, more than that, her blessing.

“Son,” she said in Spanish, her brain warring with her heart, “you’ve been gone in the Army all this time, and now you’re getting ready to leave again?”

His eyes tightened ever so slightly, steeling for disappointment. In that instant, her brain won.

“But if you think that’s where you can get your best education, you go,” she said. “Follow that man, and stay with him.”

A new future suddenly unfolded before Lauro Cavazos Jr. He was headed 600 miles away from his family’s home in Kingsville, following a cherished professor to a place he knew almost nothing about, Texas Technological College.

It was a fateful decision that altered not only Lauro’s own story, or that of his family – after two of his brothers followed in his footsteps – but that of Texas Tech University itself.

“It seemed like we took over the school,” Lauro’s brother, Bobby, later remembered.

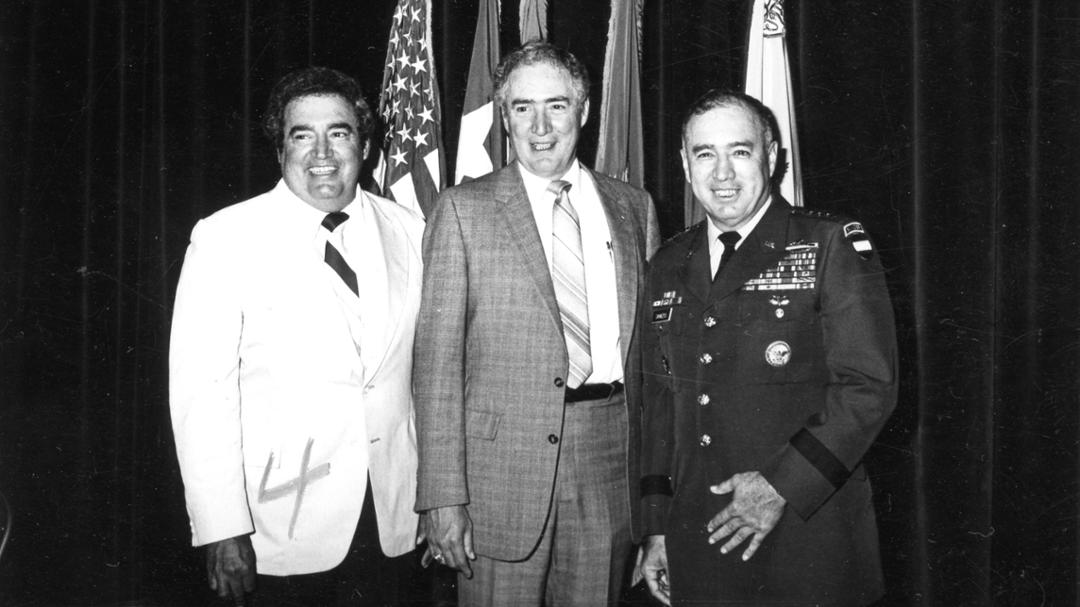

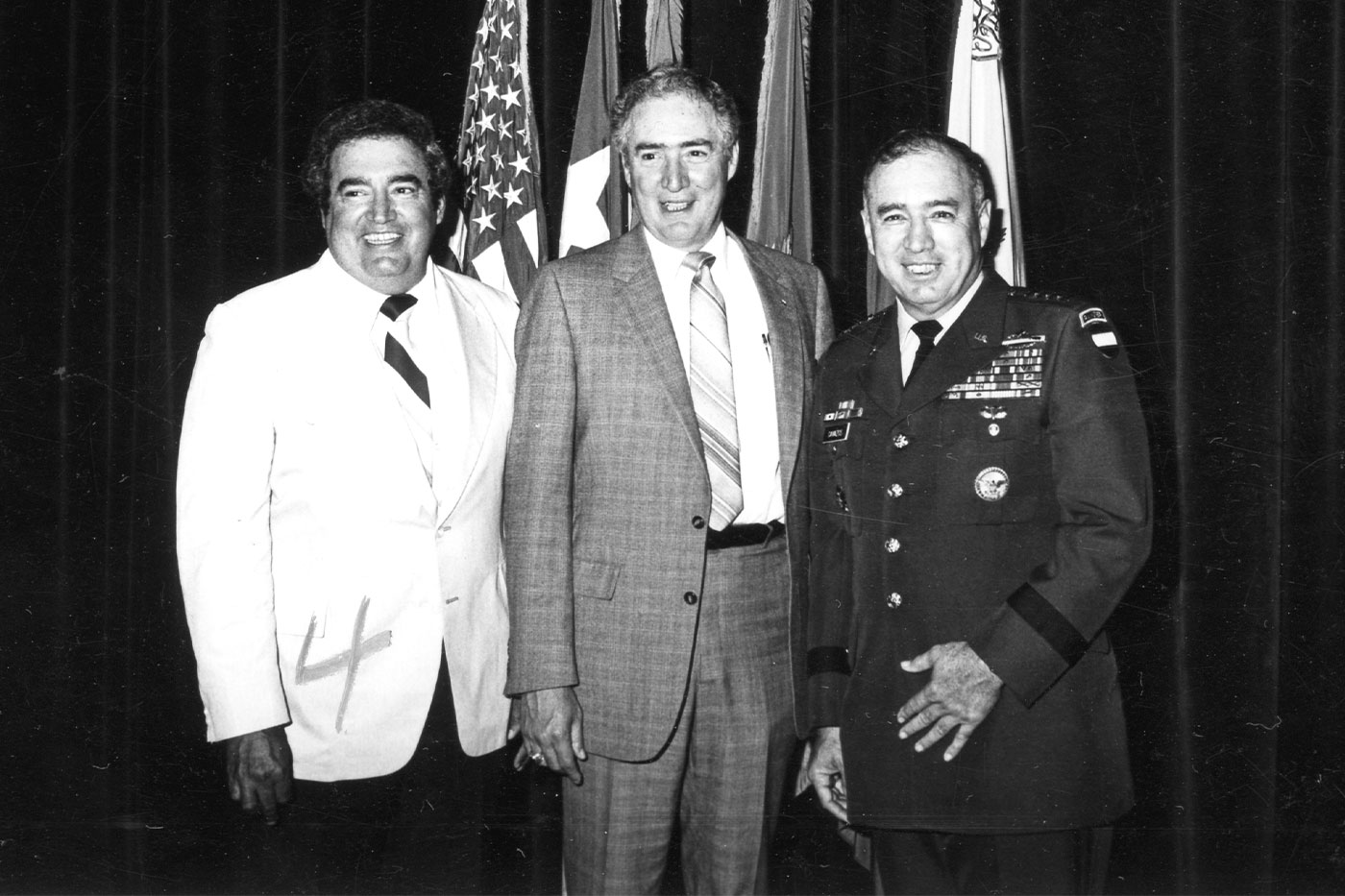

You see, while Texas Tech launched Lauro, Richard and Bobby Cavazos into the spotlight as the U.S. Secretary of Education, a four-star Army general and an NFL player-turned-country singer, respectively, the brothers also made their own indelible marks on the university.

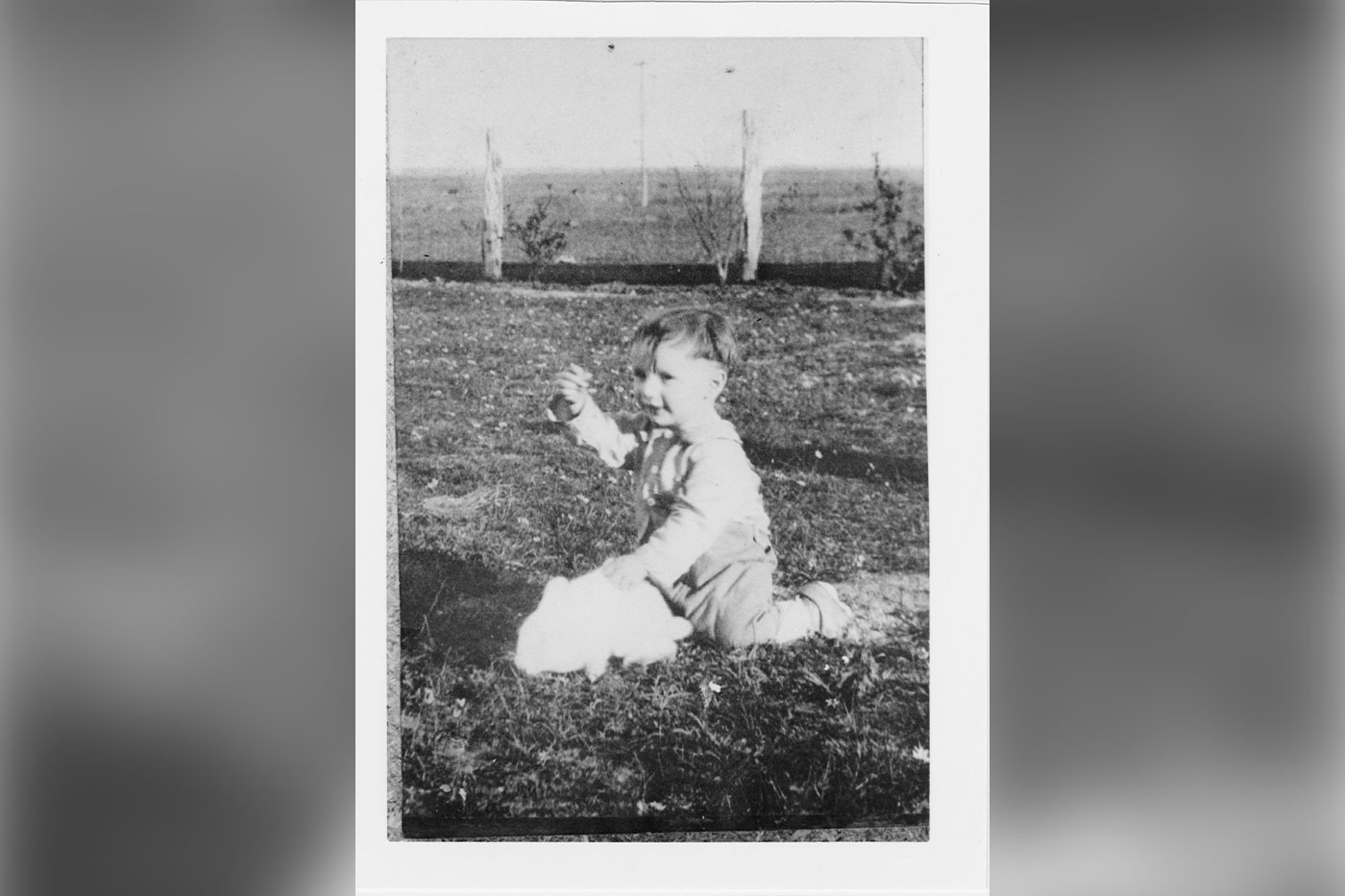

King Ranch

Of course, by the time Lauro headed off to college, blazing a trail was nothing new to any of the Cavazos family members. Like something out of an old Western, the children grew up on the fabled King Ranch, learning to ride horses and shoot, watching the vaqueros drive cattle. Lauro Jr., sometimes called “Larry,” was the studious, imaginative brother; Richard, who went by “Dick,” was the leader, directing toy-soldier armies and his brothers; and Bobby was the self-described “guinea pig,” jumping off the barn, rolling down a highway embankment and whatever other crazy schemes his brothers dreamed up.

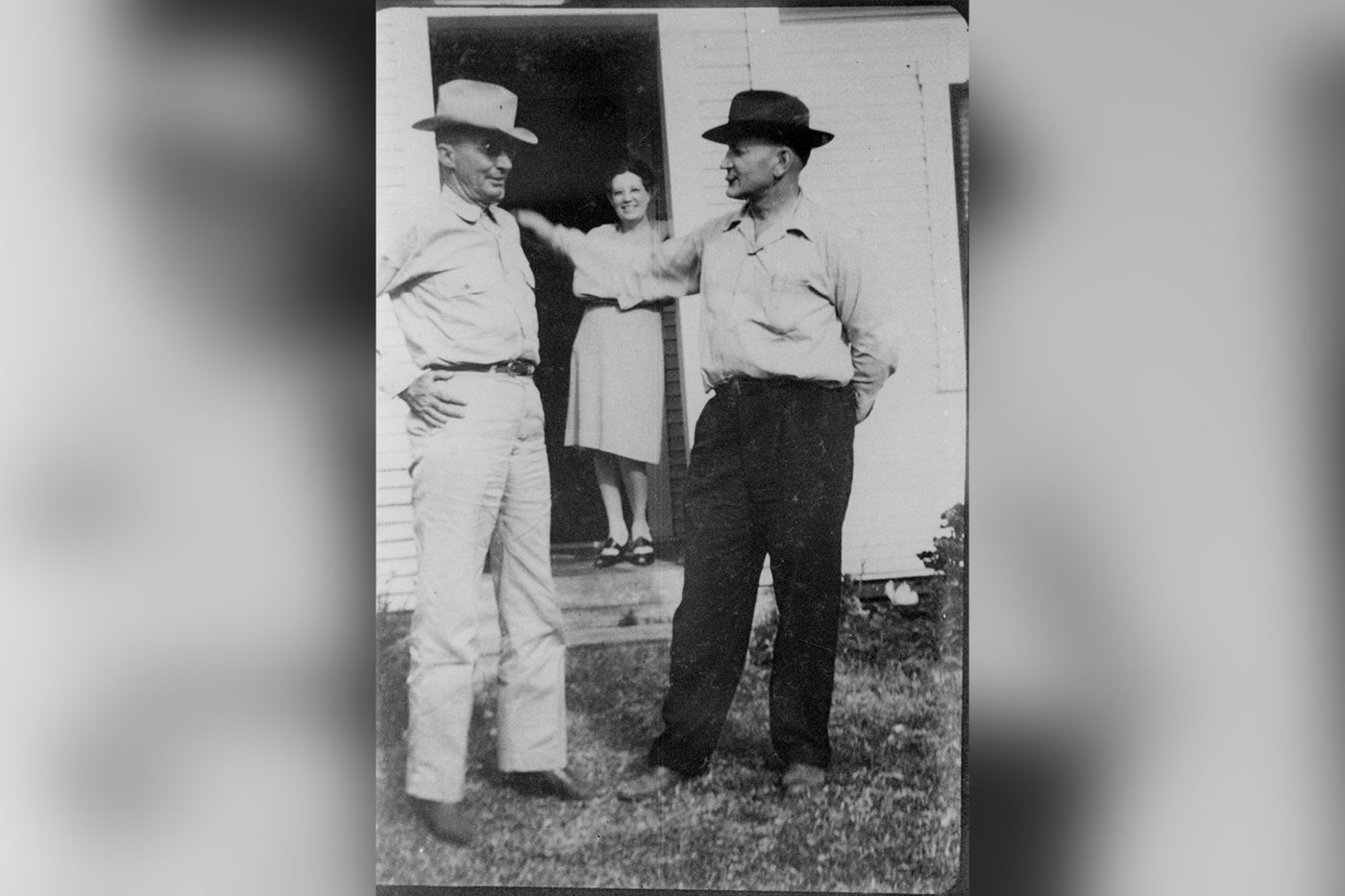

Their father, Lauro Sr., was the foreman of the ranch’s largest section and, as such, claimed a certain amount of respect, even in the nearby town of Kingsville. Most children on the ranch attended the two-room ranch school, but Lauro Sr. wanted his children educated in town.

Tomasa spoke almost no English, so the children all spoke Spanish with her – as with most people on the ranch – but Lauro Sr. insisted the children speak English to him. You see, it was the 1930s, and Kingsville’s schools were segregated. White children attended Flato Elementary, Hispanic children attended Stephen F. Austin Grade School and Black children attended Frederick Douglass School. Lauro Sr., however, wanted his children to attend Flato.

Although the superintendent of the Kingsville Independent School District objected, Lauro Sr. got his way. Sarita, the oldest child and only daughter in the family, started as the only Hispanic student at Flato, and her brothers all followed: Lauro Jr., Dick, Bobby and, seven years behind, Joseph.

The boys were bullied by their white classmates – that is, until, they began to distinguish themselves in football and track. Dick, Bobby later remembered, “wasn’t afraid of anything – he would tackle like a buzz saw.” But Bobby, particularly, caught the coach’s eye. As a junior-high schooler, he was named a manager for the high school football team so he would just naturally grow into it.

Education

Lauro Sr. and Tomasa had three expectations for their children: the boys would serve their country in the military, like their father had during World War I; all five children would go to college; and, as family, they would look after one another.

Although Lauro Sr. had an eighth-grade education and Tomasa only second-grade, they were adamant that nothing would impede their children. So, as Sarita neared high school age, Lauro Sr. bought a plot of land in Kingsville, built a house and moved his family off the ranch.

“It wasn’t until much later that I recognized what he’d done,” Lauro Jr. recalled. “In his constant insistence on our getting an education, he built that house two blocks from the elementary school, one block from the Texas College of Arts and Industries and within walking distance of the high school.”

Sarita started at Texas A&I – “now it’s called Texas A&M-Kingsville, but I can’t bring myself to call it A&M,” Lauro joked. But as he approached his high school graduation, he couldn’t focus on the future. It was 1944, and World War II was raging.

“All of us knew good and well that, come graduation, we were off to the service,” he explained. “I really didn’t plan for anything beyond graduation.”

World War II

Lauro got lucky. By the time he’d gone through training, the war was in its final months. He spent almost all of his two-year service commitment stateside and, in September 1946, was sent home. Lauro Sr. picked him up at the bus terminal and, on the way home, drove by Texas A&I. Nonchalantly, but in a tone of absolute finality, Lauro Sr. said, “Tomorrow, son, you come over here to enroll in that college.”

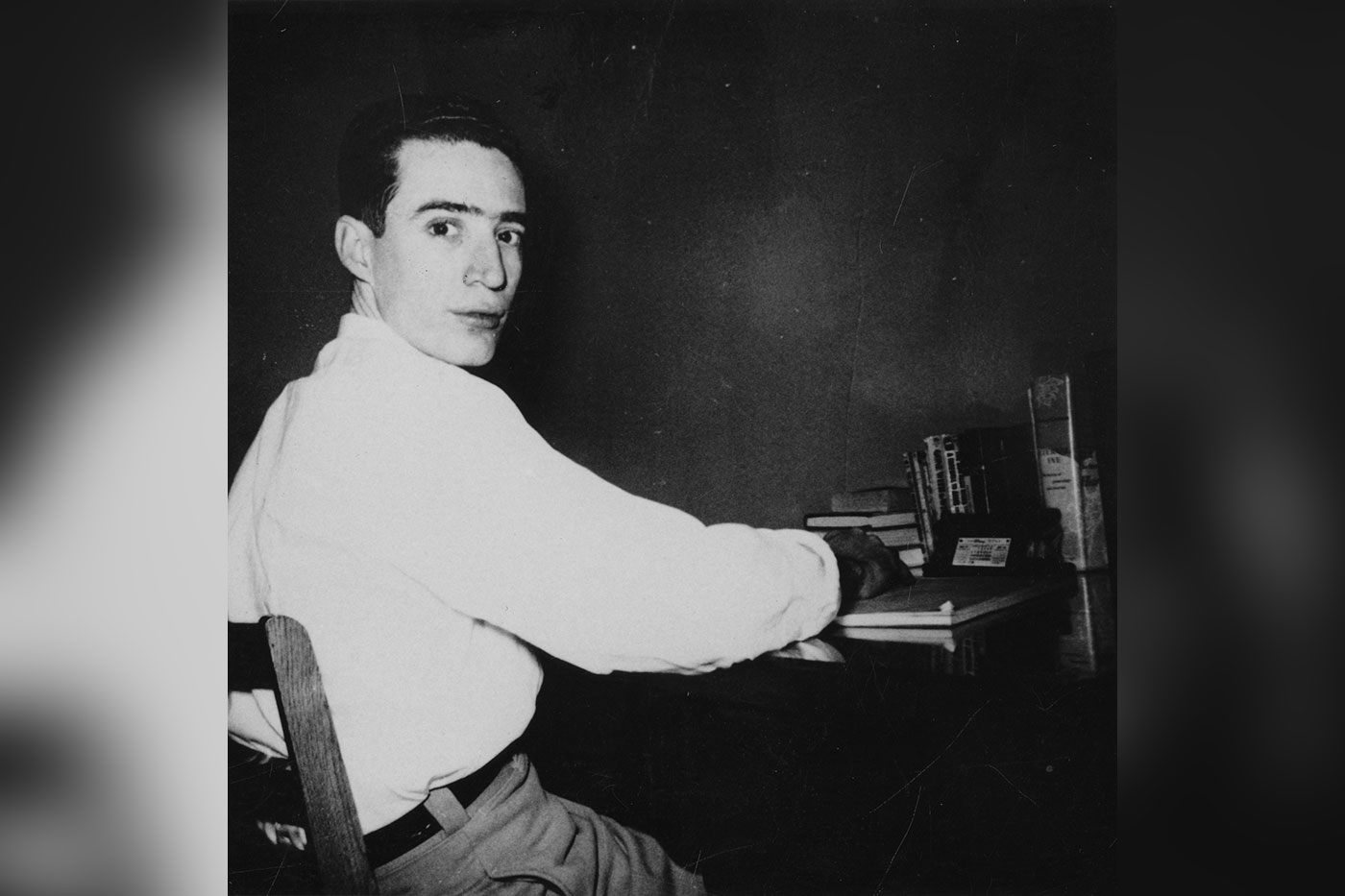

Having spent virtually no time thinking about his future, Lauro Jr. didn’t know what to major in, so he fell back on his previous interests. He’d been editor of the high school newspaper, so he chose journalism. For his required science course, he picked biology at random.

His biology instructor, however, was a man named James Cecil Cross, and to Lauro, “he made biology come alive.” By the end of the first semester, Lauro changed his major. At the end of the second semester, he got some unexpected news: Cross had been hired at Texas Technological College in Lubbock – a place on the other end of the state which Lauro knew nothing about.

Nevertheless, he knew his path was clear. He went to his mother and, in the Spanish they always conversed in, he told her, “Mom, I really have to follow Dr. Cross, because he’s such an outstanding teacher.” Tomasa, understandably hesitant, ultimately encouraged her eldest son to go where he could get the best education.

Lubbock

When Lauro arrived in Lubbock in the fall of 1947, the earth moved. Quite literally – it was blowing in the air all around him.

“It was a big sandstorm,” a 93-year-old Cavazos laughed during a 2020 phone call from his home in Massachusetts. “That’s about the best way to describe what Texas Tech was like when I showed up out there. But I had to follow that professor, so campus could have been anything.”

What it was, was booming. Lauro’s fellow World War II veterans were attending college en masse, thanks to the G.I. Bill, and Texas Tech’s enrollment that fall topped 6,000 students, up from less than 2,000 only three years earlier. The residence halls were at capacity, so Lauro rented a room nearby. Texas Tech was working to construct new buildings, but to keep up with the massive student influx in the meantime, it had bought dozens of leftover Army barracks, called “X shacks,” to use as classrooms, laboratories and faculty offices.

Lauro progressed quickly in his undergraduate studies as a zoology major. Along the way, he joined the Pre-Med Society and Alpha Epsilon Delta, a national honorary pre-medical fraternity. As his 1949 graduation neared, Lauro learned his parents were planning to make the 600-mile trip from Kingsville. He explained that his walk across the stage would last only a few seconds – hardly worth their time or trouble – and they didn’t need to come.

“Those are precious moments to your mother and me,” his father responded. “We will be there for your graduation.”

“They never, to my knowledge, missed a graduation of a Cavazos,” Lauro added.

The Brothers Cavazos

After earning his bachelor’s degree, Lauro pursued his master’s degree.

“I never dreamed I could get a Ph.D., and I wasn’t sure I could get a master’s,” he remembered. “And then I got my baccalaureate. Once I got a baccalaureate, I went right straight on through.”

Dick graduated from high school in 1947 and attended North Texas Junior College in Arlington, where he continued to play football. Bobby, as his coaches expected, was a star on the Kingsville High football team.

When Dick graduated from junior college in 1949, he came to Texas Tech like his older brother. He majored in geology and was in the Army ROTC program, but he hadn’t abandoned athletics. It wasn’t exactly a smooth start – he was the first Hispanic player at Texas Tech, and the team manager wouldn’t even give Dick a uniform until the coach ordered it. That said, as Bobby later told it, the coaches watched Dick during one practice, then told him to get his stuff and move into the athletics dorm – they were giving him a scholarship.

Bobby, who turned 18 in 1948 and, by law, could no longer play for his high school, spent the 1949-1950 academic year at Tarleton State University, during which he became the third-leading scorer in the Southwest Junior College Conference. Dick brought Bobby up to visit Texas Tech in December, while the Red Raiders were preparing to play in the Raisin Bowl, so Bobby’s first impressions of Lubbock were based on the bitter wind and concrete-like, frozen ground of the practice field.

“I wouldn’t go here for nothing,” he later recalled thinking. In addition to Texas Tech, he had been offered football scholarships to the University of Kansas, the University of Nebraska, the University of Texas, Texas A&M University, Texas A&I, Oklahoma University, Oklahoma State University and the North Texas State College (now the University of North Texas). Bobby was leaning toward North Texas, based on the college women he saw there, but another woman had something to say about that: his mother. She insisted he go to Texas Tech like his brothers.

“She knew how I was,” he laughed. “I was the rowdy one.”

So, starting in the fall of 1950, there were three brothers on campus, Dick and Bobby rooming together in West Hall and Lauro pulling many an all-nighter on research in the Chemistry building, which housed all the sciences. They began to earn the moniker that would follow them from then on: the Brothers Cavazos.

One Year Together

While their nickname would last, their time together on campus was short lived. In 1951, both Lauro and Dick finished at Texas Tech. Lauro earned his master’s degree and headed off to Iowa State University to pursue his doctorate. Dick got his bachelor’s degree in petroleum geology and was commissioned a Second Lieutenant in the Army. Bobby hung around, working toward his degree in animal husbandry.

During that one year they were all at Texas Tech together, they were plenty busy. Lauro became a member of the biology club and an officer in Alpha Epsilon Delta, now led by Dr. Cross, and was teaching freshmen zoology courses. Dick was a member of the Double T Association, which honored lettermen. Bobby was vice president of the freshman class. Dick and Bobby were in the ROTC. All three were in the Newman Club, a Catholic student group, and Lauro was its president. Dick, on the varsity football team, and Bobby, on the freshmen team, occasionally got Lauro tickets to come watch them play. Not to mention they were all studying, too.

But school wasn’t the only thing on their minds. Lauro had met Peggy Ann Murdock, an aspiring nurse from Plainview, at church. In Lauro’s lab, Dick had met Caroline Greek from Gainesville. Upon graduation, Dick attended the Infantry Officer’s Basic Course at Fort Benning, Georgia, and volunteered for a combat assignment to Korea. In between, in early 1952, he married Caroline.

Bobby, still the freewheeling college man, was focused on his successes on the field, and they were numerous. It didn’t really occur to him that Dick was heading off to war or what could happen. Dick was on leave when the Red Raiders played in the Sun Bowl on Jan. 1, 1952, so he came to watch the game and even rode on the team bus with Bobby.

After the game, the first bowl victory in Texas Tech history, Bobby was riding high. So when Dick quietly asked him for a favor, Bobby confidently said, “Sure, what?”

“If I get killed over there,” Dick said, “take care of things for me.”

The idea pulled Bobby up short. But he agreed – of course. Taking care of each other was understood.

Korea

Dick arrived in Korea that fall, assigned to the 3rd Infantry Division. Although he was offered staff assignments as a lieutenant, he wanted to be in command. It wasn’t long before he got the word he’d been hoping for – he would be taking over his own company, the 65th Infantry Regiment.

Throughout the long jeep ride to meet his company, Dick was excited. But when he arrived where they were camped, on the side of a hill, he found a group in shambles. Some, an aide later recalled, were even in leg shackles. As he went from man to man, asking questions and removing shackles as needed, Dick began to piece together what had happened.

The 65th was a regiment of the Puerto Rican National Guard. Most of them spoke only Spanish and, over the past year, many of the noncommissioned officers in charge had come to the end of their tour of duty and returned to Puerto Rico. The officers left in charge, by and large, did not speak Spanish. The communications difficulties had come to a head in late October 1952, when many of the unit’s soldiers panicked and fled the battlefield during a particularly fierce Chinese assault. More than 90 of them were court martialed, and the entire regiment had been sent for retraining.

Because of his bilingual upbringing and his inherent leadership qualities, Dick was able to turn the regiment around. They were not cowards, he noted, just good soldiers who had been poorly trained and poorly led. Under his command, they captured a wounded enemy soldier – the height of honor – under intense Chinese fire on Feb. 25, 1953. Leaving a small force to cover him, Dick recovered the man alone, for which he earned his first Silver Star. In May, during an enemy attack on a critical position called OP Harry, Dick personally repaired a vital communications wire under heavy artillery, earning the Bronze Star for Valor.

The following month, Dick led a raid against Chinese soldiers on a hill overlooking OP Harry. The enemy was stationed on the hill, from which they were perfectly positioned to attack the outpost. The 65th was ordered to retake the hill and hold it, preventing a Chinese assault. Just before dusk on June 14, 1953, they advanced.

Immediately under fire, Dick urged the company forward. Unlike some commanders, he always went with his troops into battle, and this was no different. In taking the hill, nearly one-third of the 65th Regiment was wounded or killed. Three hours later, just after midnight, having prevented an attack on OP Harry, the regiment was ordered to withdraw. Dick was unwilling to leave any comrades behind, so as his company pulled back to friendly lines, he returned again and again, personally evacuating five wounded soldiers. Dick was awarded the nation’s second-highest recognition for valor, the Distinguished Service Cross, and the entire company was honored for its bravery.

Afterward, back in friendly territory, a soldier pointed out that Dick’s back was bleeding. The battalion surgeon later extracted shrapnel and small rocks picked up by the artillery blasts. Unknown to Dick, the surgeon submitted his name for the Purple Heart.

And more than 70 years later, on Jan. 3, 2025, he was awarded a posthumous Medal of Honor “for conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty.”

Dick’s plan had been to serve in the military for two years to qualify for the G.I. Bill, then go back to studying geology – and he’d almost reached those two years. But after telling his commander these intentions, the man replied, “If all you guys get out, you’ll always have a mediocre Army.”

To Dick, who had served honorably and even been wounded in battle, this felt unfair. But after thinking it over, he realized he couldn’t leave the military. So after the armistice was signed on July 27, Dick returned home in September 1953 to a command position at Fort Hood.

The National Football League

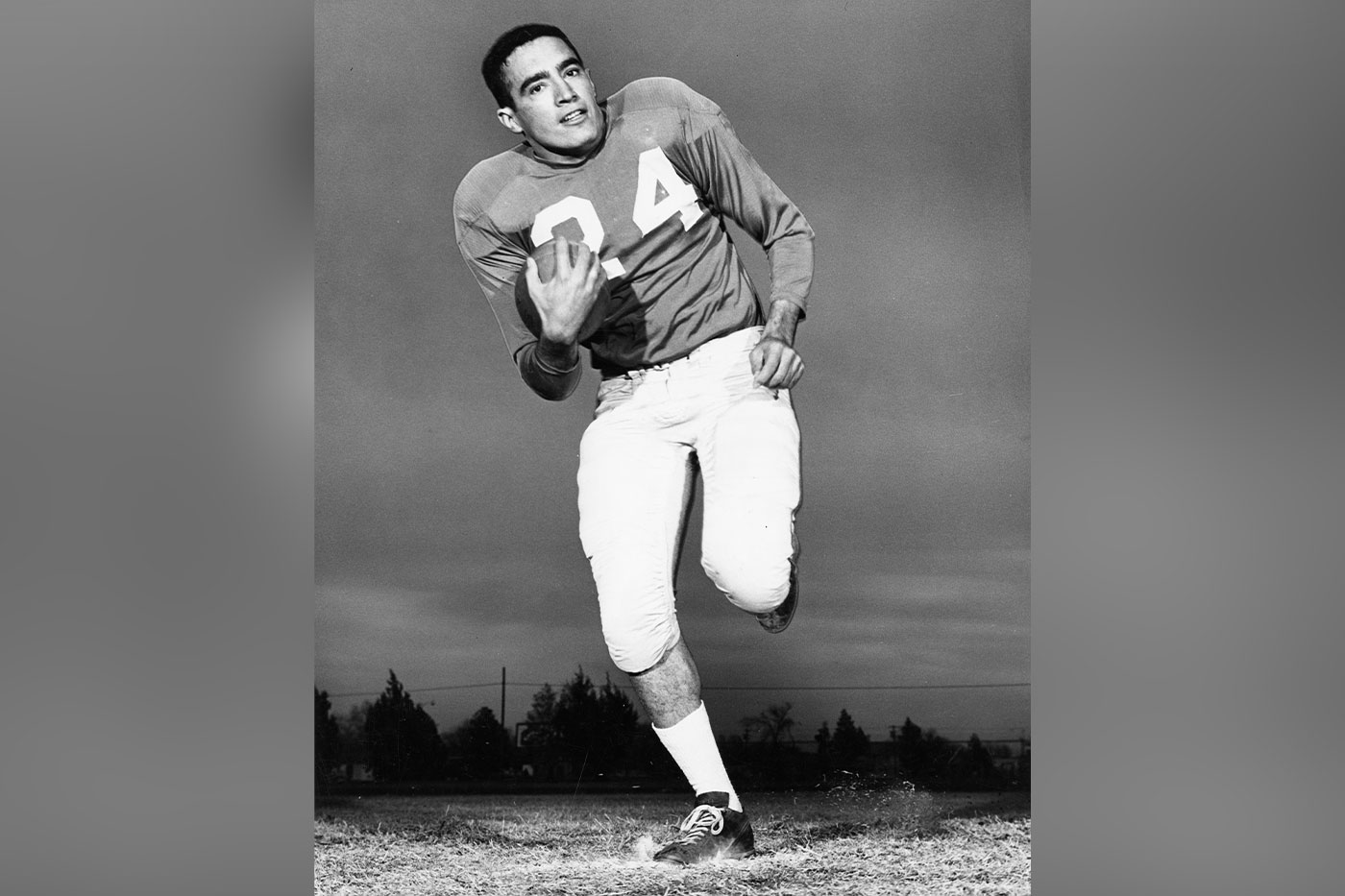

While Dick was making a name for himself in the military, Bobby was back in Lubbock, making a name for himself on and off the football field. He’d become a star rusher for the Red Raiders, but his fame extended outside of Lubbock.

Heading into the Jan. 1 Gator Bowl against Auburn at the end of the 1953-54 season, Bobby also was scheduled to play in the Senior Bowl a week later, highlighting some of the best draft-eligible college players. The 190-pound halfback was named All-Border Conference and made the Associated Press All-American second team – the first Red Raider to do so. He was the second-highest scorer in the nation, setting a university record with 80 points in one season, and the Red Raiders, with a 10-1 record, were the highest-scoring team.

He certainly lived up to his record in the Gator Bowl. Bobby scored three of Texas Tech’s five touchdowns, pushing the team to a 35-13 win, and was named the Red Raiders’ most valuable player of the game.

Four weeks later, on Jan. 28, the Chicago Cardinals selected Bobby as the 26th pick in the NFL draft. Bobby was even named Mr. Texas Tech in the 1953-54 La Ventana yearbook, a point he still took pride in years later.

But life on the field certainly wasn’t everything. The previous year, Bobby had met a pretty first-year student named Nancy Chastain from Breckenridge, and the sparks flew. On Feb. 27, 1954, they got married, with Dick as Bobby’s best man.

Bobby, who was supposed to graduate in May 1954 and report to the Army, instead got a six-month deferment. He put the very end of his college education on hold as he headed into NFL training camp.

It didn’t have to hold long. On Nov. 21, in what would turn out to be the Cardinals’ second and last win of the season, Bobby was knocked out cold. He awoke to a career-ending shoulder separation. While, officially, he was on the injured reserve list, he walked away from the NFL.

Bobby returned to Texas Tech and served as an assistant coach for the freshmen team while finishing his degree in animal husbandry. He graduated in May 1955, and then the Army sent him to Korea. But it was a much different experience than Dick had there.

“When Bobby first got to Korea, he was stationed at the 38th parallel,” Nancy said. “Then they found out who he was, and he was transferred away from the Demilitarized Zone and assigned to coach the Army football team there. They won the championship.”

Family Ties

Lauro, meanwhile, had progressed through his doctorate in physiology at Iowa State. For six years, he and Peggy had maintained their courtship mainly through letters and phone calls. As Lauro Sr. and Tomasa prepared to travel up to Ames for their son’s graduation, they invited Peggy to come, too. After dinner with his parents, Lauro took Peggy out onto the campus and proposed to her.

He admitted he couldn’t give her a ring, because he had only $400 to his name – exactly the amount he needed to take a summer course in neuroanatomy so he could be hired in the fall to teach at the Medical College of Virginia. She accepted anyway, on one condition: she wanted 10 children. Lauro agreed.

They got married in Lubbock, where Peggy was working as a nurse at West Texas Hospital, but her family put a damper on their celebration. “Peggy’s father wouldn’t give her away,” Lauro recalled. “He thought it was awful that she was marrying a Mexican. Her brother wouldn’t either.”

Nevertheless, Lauro was hired that fall, as planned, and they started their family. Peggy got her wish – she gave birth to 10 children in 10 years – and worked as an operating room nurse, while Lauro taught anatomy at the Medical College of Virginia. In 1964, he moved the family to Boston for his new job at the Tufts University School of Medicine. While at Tufts, he sometimes taught classes at Texas Tech and its School of Medicine, which had opened in August 1972, but he also had his plate full in Boston. In 1975, he became dean of the Tufts medical school.

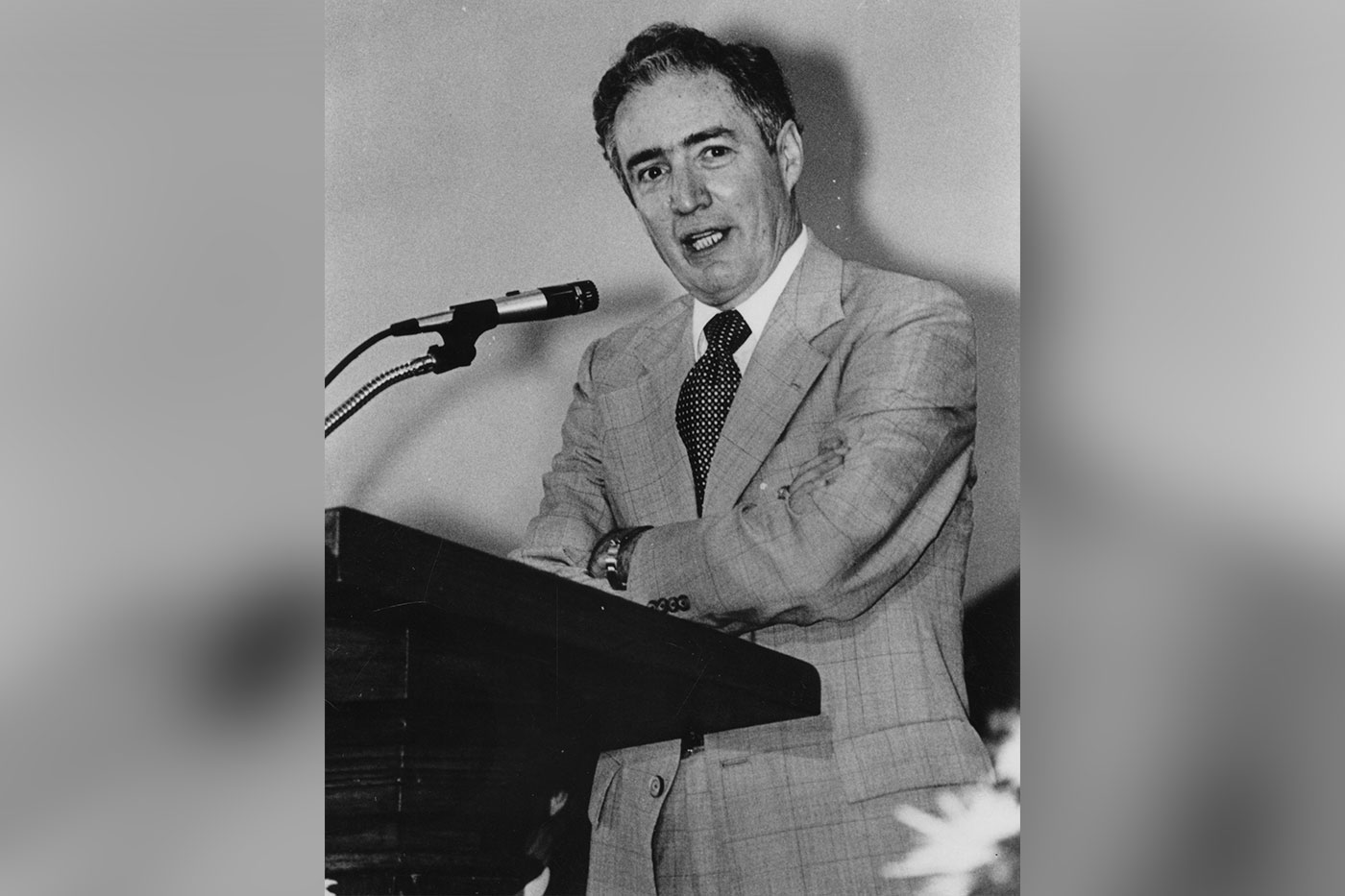

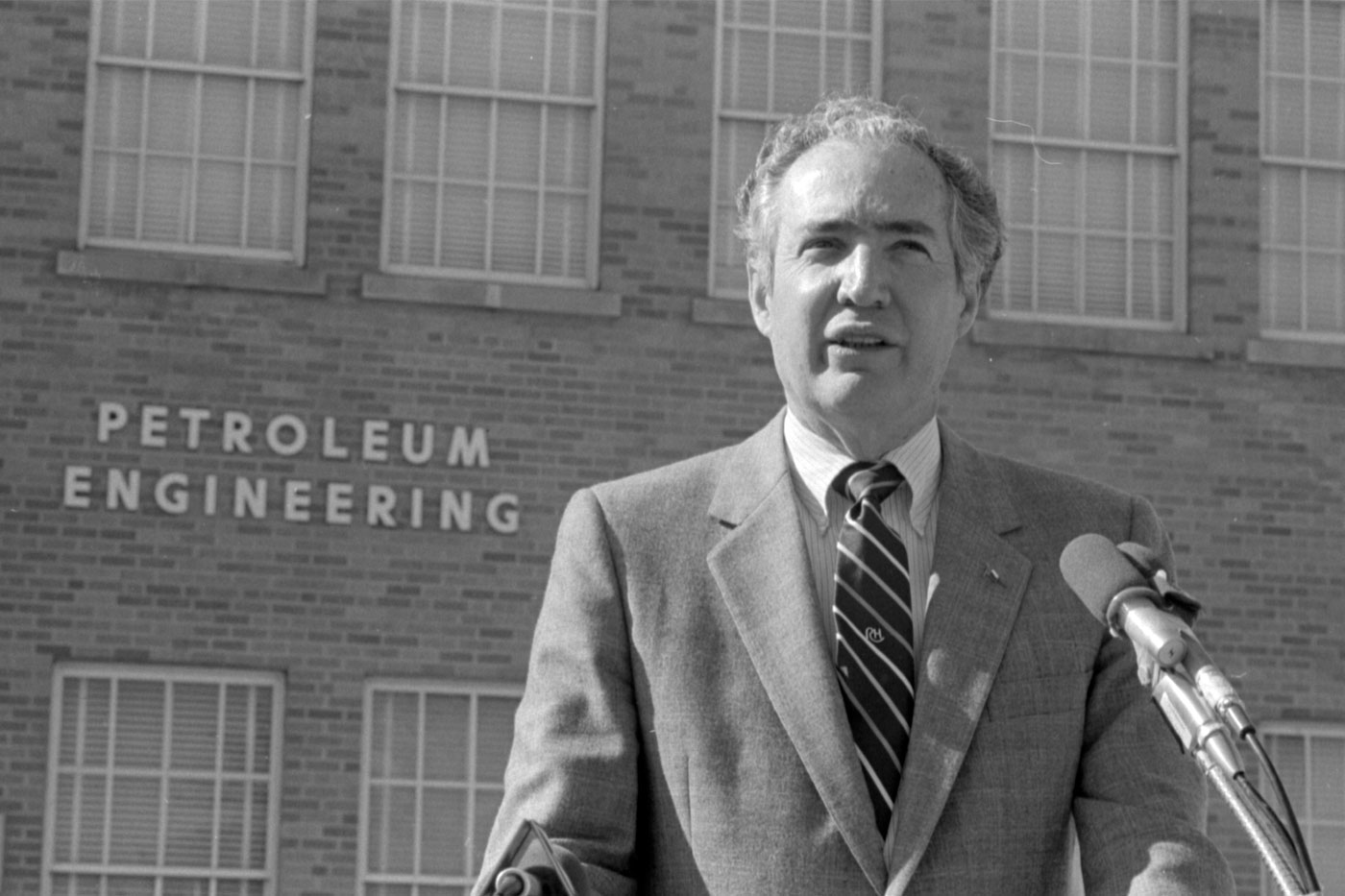

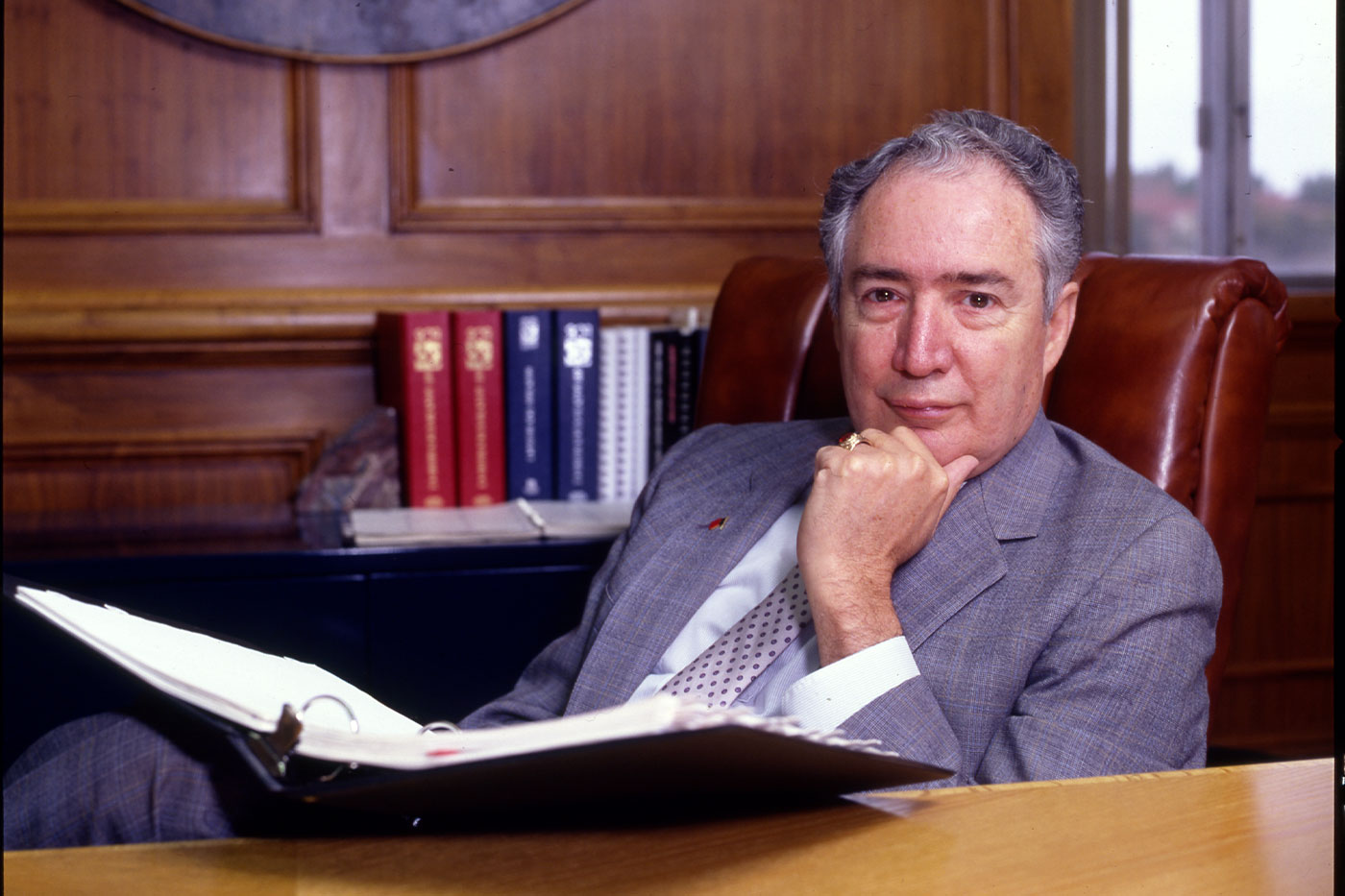

He admits he probably would have stayed there for the rest of his career if he hadn’t gotten an offer he couldn’t refuse. In June 1979, Texas Tech’s ninth president, Cecil Mackey, was named the new president of Michigan State University. During the search process, Texas Tech representatives reached out to Lauro, who had been named a distinguished alumnus in 1977.

“I had never dreamed of the possibility of being Texas Tech’s president,” he said. “But I couldn’t resist – it really was probably the only place that could have moved me.”

So, on April 1, 1980, he took the reins. Part of the appeal was that he was Texas Tech’s first alumnus to be its president, and he wanted to help improve his alma mater. Another aspect was that he was Texas Tech’s first Hispanic president, and at the time, there were only four or five major college presidents who were Hispanic. But perhaps the strongest reason was his family connection to the university.

You see, Texas Tech no longer belonged just to Lauro, Dick and Bobby. They’d all met their spouses there, and their children had become Red Raiders.

“It was very much our institution,” Lauro explained. “When I was chosen president, I had two children enrolled here.”

Perhaps family finally won out. Although Peggy’s family never apologized for their treatment of Lauro, when he was inaugurated as president, they came to his celebration.

Vietnam

After his time in Korea, Dick kept busy with his military duties at Fort Hood and his home duties, helping raise his and Caroline’s four children. But, from 1958 to 1960, he made time to teach military science classes at Texas Tech. And then, in the mid-1960s, the Vietnam War heated up.

In the fall of 1967, Dick – by then a lieutenant colonel – was commander of the 1st Battalion, 18th Infantry Regiment, known as the “Dogface battalion,” as it fought North Vietnamese soldiers near the Cambodian border. On Oct. 30, during an attack at Lộc Ninh, Dick again distinguished himself.

During a search-and-destroy operation through a large rubber plantation, one of the companies under his command suddenly came under a barrage of fire from enemy soldiers entrenched on a hillside. Without hesitation, Dick led the other companies in an attack on the North Vietnamese forces. As the opponents fell back to more fortified positions on the hill, Dick called in air strikes to cut off their retreat. Unable to flee, the enemies advanced toward Dick’s unit.

Randolph House, Dick’s aide de camp for nearly four decades, later described the situation as “so bad Lt. Col. Cavazos ordered the men to fix bayonets; he even had to use his pistol when his M16 ran out of ammo. For the boss to resort to the .45 pistol, which he said was a fine weapon in a crowded elevator, things must have been very bad.”

Soon they were so close that the air strikes had to be called off for fear of hitting the American troops. Disregarding his own safety, Dick led a charge straight into the North Vietnamese soldiers. Overrun, the enemy retreated toward the top of the hill, now safe in the absence of air strikes, and Dick ordered artillery fire that wiped them out, ending the battle.

He was subsequently awarded a second Distinguished Service Cross for “brilliant leadership in the face of grave danger” and “extraordinary heroism.” But all accounts of what transpired came from others – the battle-hardened officer would never again talk about that day.

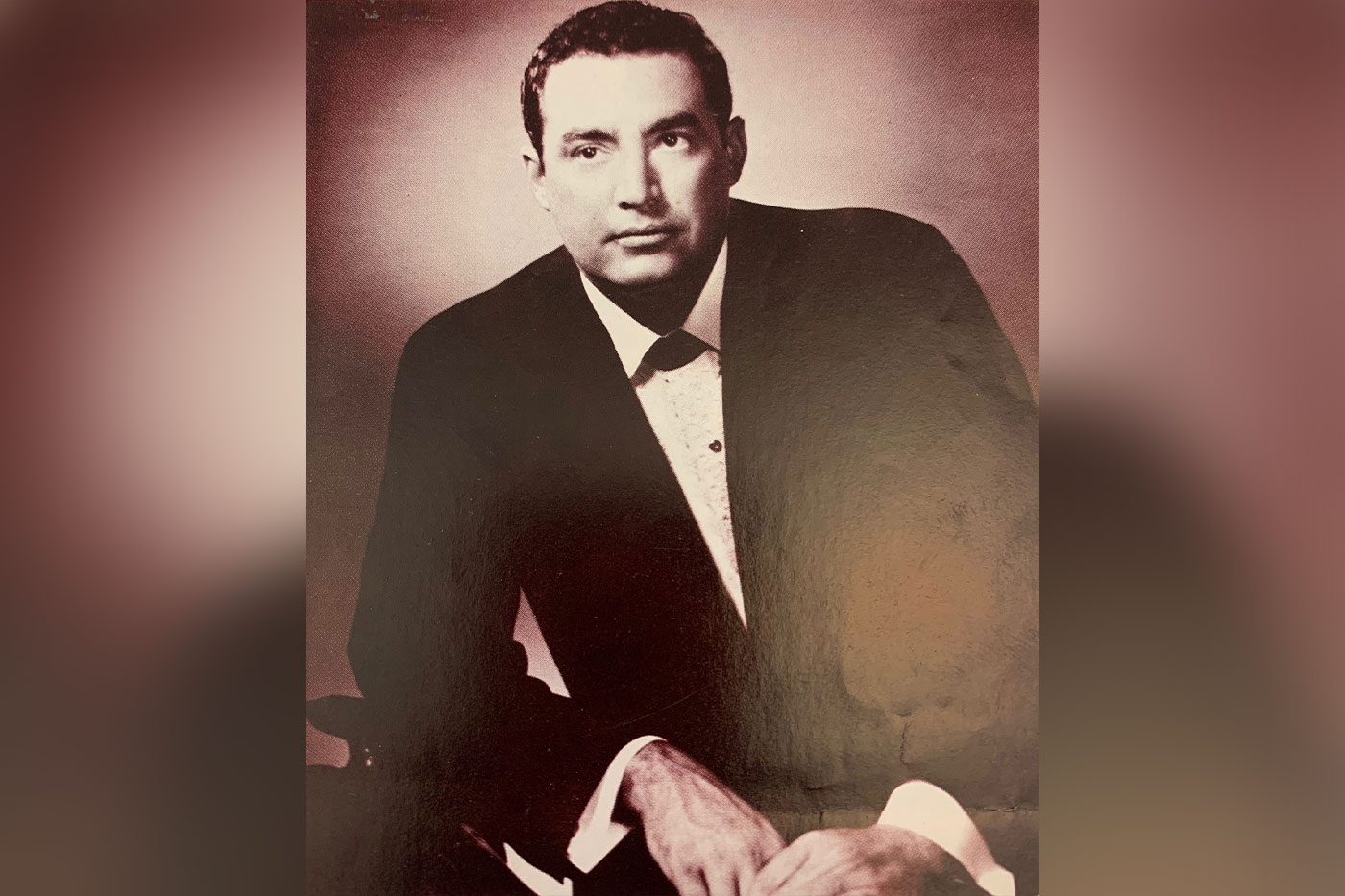

Radio Star

Returning home from Korea in 1957, Bobby went home to the King Ranch to make the most of his degree in animal husbandry. While he acknowledged many people might have been crushed by such an end to an NFL career, he wasn’t. For one thing, he explained years later, the NFL wasn’t such a lucrative career choice back then – he had signed with the Cardinals for only $20,000, which was much easier to walk away from.

“There were a lot of guys that football was the only thing they had going for them,” Bobby said. “But I knew I had my job back there with dad on the King Ranch, because I had worked for him every summer.”

Back at the ranch, he worked for Lauro Sr. in the Santa Gertrudis Division and started a family with Nancy. After his father’s death in November 1958, Bobby was the Santa Gertrudis Division’s assistant foreman for nearly a decade – but even so, he never quite resolved himself to the quiet, ranching life.

While riding around the ranch, Bobby passed the time and staved off the loneliness by singing to himself. Then friends began to ask him to sing at parties and gatherings. Eventually, he began to receive invitations to sing at dances and clubs.

A friend managed the Americana Motel’s Fiesta Club in the nearby town of Alice. Because they never had much of a crowd on Saturday nights, his friend let Bobby do a weekly show – and it wasn’t long before the crowd appeared. Bobby, who had entertained his college teammates by singing and playing the guitar, attributed his stage presence to his time on the field.

“I think I owe a lot to my football career,” he said in the early 1960s, “because the confidence it gave me probably accounts for my feeling at ease singing before the public.”

So Monday through Friday, Bobby was a cowboy, riding the range and driving cattle. The rest of the time, he was a county and western singer. On weekends, he performed live; on vacations, he recorded demonstration tapes.

In 1962, he released his first recording from the Dante label, a 45 under the name Bobby Cavazos and the Epics. The following year, a friend introduced him to country and western star Ray Price, who sent him to Nashville to record a new demo. Price signed Bobby to a contract, but – explaining that northern disc jockeys might not be able to pronounce “Cavazos” – Price changed Bobby’s stage name to Bobby “King” Rio, a reference to both the King Ranch and south Texas’ Rio Grande Valley.

Under the Mercury Record Corporation, he released a 45 with “Texas Leather and Mexican Lace” on one side and “Quatro Rosas (Four Roses)” on the other. The songs began to get significant radio air time, especially in South Texas and the desert Southwest. “They are certainly not a smash like the Beatles,” Bobby said at the time, “but they are doing all right.”

Not long after, the songwriter Boudleaux Bryant, who wrote several songs for the Everly Brothers, called Bobby on a completely unrelated topic – he was asking about some Santa Gertrudis cattle from the King Ranch. But while on the phone, Bryant asked for Bobby’s demo tape, and Bobby forwarded him to Price. The very next evening, Bryant called back. He’d played Bobby’s tape for Fred Foster, president of Monument Records, and Foster wanted to offer Bobby a contract.

“I was especially pleased because they were opposed to the use of a stage name and much preferred using my own name,” Bobby said.

Foster recognized that Bobby’s name might still be remembered from his football-playing days, which Bobby considered a huge compliment. Bobby’s career was taking off as he appeared in shows with the likes of Johnny Cash, Minnie Pearl and Jim Reeves. But his stage time was increasingly taking away from his time on the ranch, and his bosses began to lose patience. They wanted him to make a decision: come back to the ranch or don’t.

As the father of three young children, the choice was clear. Bobby ended his singing career and went home to the King Ranch, where he became foreman of the Laureles Division and began an eight-year term as a Kleberg County commissioner.

In 1975, Bobby and Nancy moved nearer to her hometown of Breckenridge. They settled on a ranch south of town, where Bobby raised cattle of his own and worked part time for oil companies, negotiating contracts and leases with his fellow landowners – a booming business at the time.

Big Man on Campus

Returning to Texas Tech in 1980, Lauro was struck by the consistency he found since his days as a student.

“Really, there was no major change, it was pretty much the same way,” he recalled. “Very friendly – a little bit of sand would occasionally blow. It was just a place where you felt at home and that you could go to any of your faculties and ask questions.”

In fact, in some ways, the campus hadn’t changed enough.

The X shacks, for instance, were still all over campus. Not only were they an eyesore, they also limited the funding Texas Tech could receive from the Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board. Because of the square footage they added, the X shacks made it appear on paper that Texas Tech had too much space for its current number of students and did not need the funding it was requesting to build new facilities.

Lauro’s predecessor had already requested money for a new music building and been turned down. So Lauro picked up the fight, promising to tear down the X shacks if the board would approve the exchange. Having taught in the X shacks himself, he attested to their inadequacy – and the board finally relented.

“We used to say that the X shacks would be here on the campus until we had grass on the campus,” he joked. “Sure enough, that’s about the way it worked out.”

Campus beautification, accordingly, became one of Lauro’s many priorities. There were no plants. The entrance was so negligible it was easily overlooked. But Texas Tech always flew the U.S. flag in the middle of Memorial Circle, so Lauro led the charge to put up two more flagpoles – one for the Texas flag and one for the Texas Tech flag.

His favorite change, however, was to the Administration Building. The breezeway through the middle of the building had been blocked up with chicken wire and big glass doors to prevent the wind whipping through. Even as a student, Lauro had hated the doors. Now, as an administrator, he realized they couldn’t have been part of the original architectural plan. The university’s Founding Day pictures showed he was right.

But his plan to get rid of the doors wasn’t immediately well received – at least not by the man in charge of the university’s facilities.

“It was like he thought I wanted him to blow up the building or something,” Lauro recalled.

Over the man’s objections, Lauro declared his intentions to restore the building to the way the architect originally wanted it.

“I never found out who put those doors in, but I’m the guy who took them out,” he said proudly. “It opened up that beautiful, open space there. It’s one of the few things I did around here that nobody complained about.”

As president, he made a point to show off the mural inside Holden Hall’s rotunda. He helped the National Ranching Heritage Center grow. He pushed for the restoration of the Dairy Barn rather than letting it be torn down.

“I tried to save those things that really meant something for us, the university, and had a purpose, and that’s what we did,” he said. “I’ve seen a lot of university campuses, but few can hold a candle to what we have here at Texas Tech.”

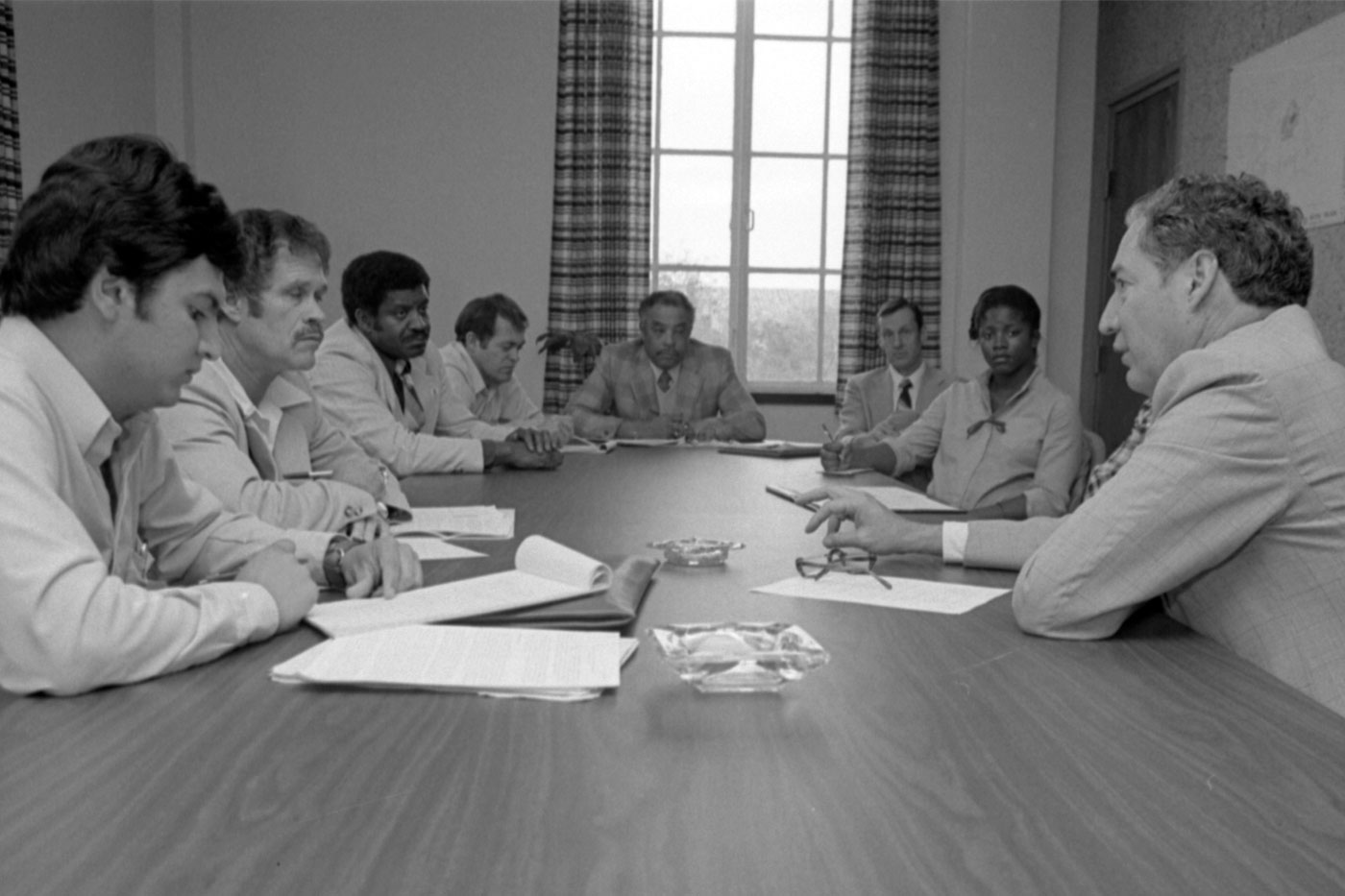

Lauro admits campus beautification probably isn’t what most people think a university president should be doing, but to him, it just made sense to make the university more attractive. And besides, he also had plenty of other things on his plate. Because the Texas Tech University System did not yet exist, the university president was in charge of both Texas Tech and the Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center (TTUHSC).

The TTUHSC was only a decade old, so Lauro directed its growth and development, nearly doubling its operating budget and expanding its academic programs. He helped launch the School of Nursing and the School of Allied Health, solidifying its position as a health care institution, and oversaw more than $27 million in facilities development at all four of TTUHSC’s regional campuses.

At Texas Tech, he spearheaded efforts to improve external relations, enlisting the university’s friends and supporters to increase its visibility in Austin. He increased the number of alumni chapters from seven to 75. He launched the university’s first major capital campaign, which raised $75 million – exceeding its goal.

At both universities, he improved academic quality, built endowments and emphasized research, the significant first steps in Texas Tech’s recognition as a Tier One national research institution more than 30 years later.

Some of his actions weren’t appreciated on campus. He amended the faculty tenure policy, adding periodic reviews that the faculty roundly rebuked. Comparatively low faculty salaries were also an issue – one he couldn’t address thanks to statewide funding shortages in the aftermath of the oil bust of the 1980s. The Faculty Senate eventually gave him a “no confidence” vote, much at odds with the faculty advocate reputation he earned throughout the rest of his career.

But Lauro wasn’t just making an impression at Texas Tech. By leading a major university, he was also expanding the reach of his influence, even becoming a consultant to the World Health Organization and other national and international public health groups. He also was a vocal proponent of education for minorities, particularly Hispanic students, which earned him the 1988 National Hispanic Leadership Award in the field of education from the League of United Latin American Citizens.

It goes without saying he was already on the national radar in education. Shortly after Ronald Reagan was elected President of the United States in November 1980, his team reached out to Lauro about the possibility of becoming the U.S. Secretary of Education. But Lauro, who had been at Texas Tech only six months, didn’t want to leave the university in a lurch. After Lauro initially declined, the Reagan team persisted. He even received a letter from Vice President-elect George H.W. Bush.

In light of Lauro’s polite, but firm, refusal, Reagan ultimately chose William Bennett for the position. But, apparently, there were no hard feelings. In 1984, Reagan gave Lauro an award for Outstanding Leadership in the Field of Education.

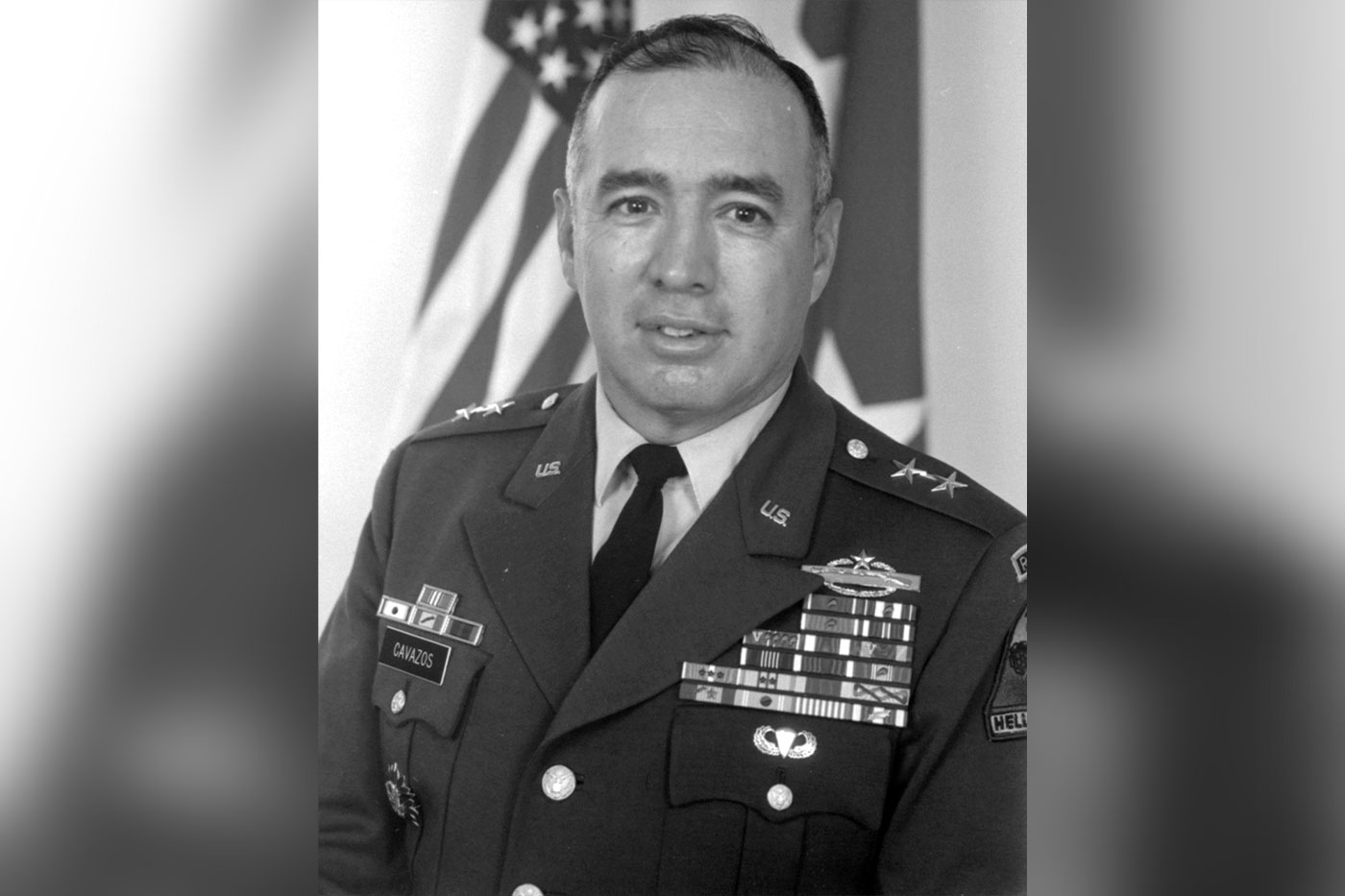

Four-star General

After returning from Vietnam, Dick continued to rise through the ranks. In 1976, upon receiving his first star, he became the first Hispanic brigadier general in the U.S. Army. Subsequently, he became the Army’s first Hispanic major general, lieutenant general and four-star general.

In 1980, he assumed command of the III Corps at Fort Hood, where he was recognized for his innovative leadership. Upon receiving his fourth star two years later, he took the reins of the U.S. Army’s largest command, the U.S. Army Forces Command at Fort McPherson, Georgia. He became an ardent supporter for the National Training Center, which enormously influenced the war-fighting capabilities of the U.S. Army.

As his aide-de-camp House later remembered, Dick always emphasized discipline. “He would say to young officers and non-commissioned officers that if they walked past an act of ill-discipline without correcting it, they were signing the soldier’s death warrant in combat.”

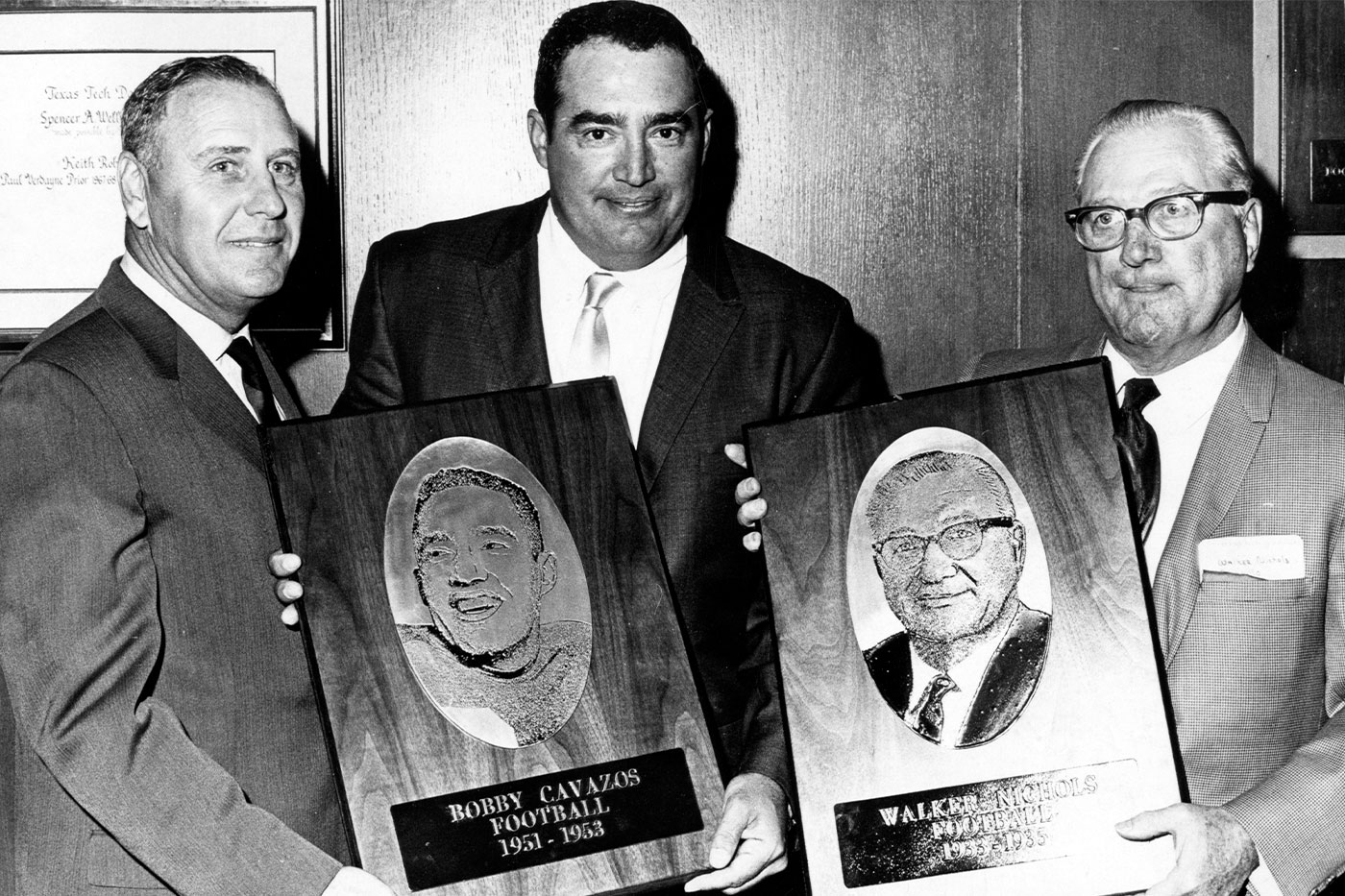

In 1982, Dick was inducted into the Texas Tech Athletics Hall of Fame in recognition of his football career – a nice addition to the Distinguished Alumnus award he’d received from the university’s Ex-Students Association six years earlier – and returned to his alma mater to give the spring commencement address. Lauro, there as the university president, still remembers the pride he felt, watching his younger brother and seeing the outstanding man he had become. Bobby was there, too – his son was graduating.

Dick retired from active service in the summer of 1984 as one of the Army’s most decorated officers. He was twice awarded the nation’s second-highest combat decoration, the Distinguished Service Cross, twice awarded the Silver Star, five times awarded the Bronze Star with V Device and received 29 other combat awards, including the Purple Heart. He also was an Airborne Ranger qualified and wore one star on his Combat Infantryman’s Badge. In addition to his Texas Tech hall of fame honors, Dick also is in the U.S. Army Ranger Hall of Fame and the Fort Leavenworth Hall of Fame.

Paying It Forward

Even decades after leaving the King Ranch, the King Ranch never really left Bobby. In his later life, he wrote and published two historical fiction novels about life there: “The Cowboy from the Wild Horse Desert: A Story of the King Ranch,” and “The Cowboy from the Wild Horse Desert, book two: The Saga Continues.”

Over the years, Bobby was honored for his athletic prowess numerous times. A mere 15 years after his senior season, Bobby was inducted into the Texas Tech Athletics Hall of Fame in 1968. In 1999, he was named to the Lubbock Avalanche-Journal newspaper’s list of the South Plains’ top 100 athletes of the century. He was even posthumously included in the Texas High School Football Hall of Fame’s 2018 class.

But even as he grew further removed from his football-playing days, Bobby nevertheless stayed close to Texas Tech, particularly Texas Tech athletics. As a member of the Red Raider Club, back when it had few members and not much funding, Bobby helped rectify both issues. With the name recognition he still enjoyed, Bobby built membership and helped raise money for a new practice facility.

The Texas Tech Athletic Training Center – better known on campus as “the bubble” – opened in 1986. Thirty years later, it was still one of the best indoor facilities in the Big 12 conference and one of only two facilities in the nation with an inflatable membrane roof. But after that roof collapsed following a severe winter storm, the building was replaced by the Sports Performance Center in 2017.

Bobby took a great deal of pride in his university, saying in his later years, “Texas Tech is the most beautiful school in the whole dadgum world and has the most wonderful people. It has been a great, great part of my life and will always be.”

Bobby died in November 2013. He was 82.

U.S. Secretary of Education

By early 1988, Lauro could tell his time at Texas Tech was coming to an end. In fact, he’d already scheduled his last day for the following summer, giving the university 14 months’ notice so it could begin searching for his replacement.

“I was 61 years old,” he said. “I had my eight years – it was time to shuffle off.”

It had been an exhausting eight years, trying valiantly to lead two major universities simultaneously. It was a job, Lauro had recently become convinced, that was better handled by a separate president at each university and a chancellor leading a unified university system.

At about the same time, Bennett announced his resignation as U.S. Secretary of Education. Again, the Reagan team came calling – only this time, Lauro was ready to answer. Because Reagan’s second term was nearing its end, Lauro knew his appointment could be very short indeed – there was, after all, no guarantee the next president would reappoint him. But since he and Peggy intended to return to Lubbock afterward so he could continue teaching in the School of Medicine, a short appointment suited him just fine.

So Lauro and Peggy went to Washington to meet President Reagan and Vice President Bush. Lauro was immediately impressed with the president, finding him a man of dignity, thoughtfulness, ideas, communication and, above all, respect. Upon meeting Lauro, the vice president shared that he already knew Dick and thought the world of him. “I wish I could get him involved in the administration,” Bush told Lauro with a laugh, “but Dick’s too smart.”

Bush, who was already running to be the next president, had announced on the campaign trail his intention to be the “education president.” Lauro expressed his support for that goal.

On Aug. 9, 1988, Lauro was nominated to be the new U.S. Secretary of Education. On Sep. 20, he was unanimously confirmed by the U.S. Senate, becoming the first Hispanic American ever to hold a cabinet post. In November, Bush won the presidential election. After Lauro congratulated him during a holiday reception, Bush asked Lauro to come visit him that weekend.

During their meeting, Bush told Lauro about the goals he wanted to see accomplished in the Department of Education. He supported bilingual education. He wanted to bring in the best people, regardless of political affiliation, and he wanted to see ethnic minorities and people with disabilities represented in the department.

“I was convinced,” Lauro recalled. “He asked me, therefore, to stay on – which I did, obviously.”

Lauro remained the U.S. Secretary of Education until December 1990. During his short tenure, he initiated special programs to fight substance abuse in schools. He advocated for stronger parental involvement in education and community-led reforms that would raise standards and expectations among students, teachers, administrators and parents.

In the face of a 37% dropout rate among Hispanic students, he chaired the Task Force on Hispanic Education, which led to Bush’s executive order establishing the President’s Advisory Commission on Education Excellence for Hispanics. It was the nation’s first organization dedicated to highlighting the needs of Hispanic students and working to overcome barriers, but it would not be the last – all presidents since have signed similar orders.

“We did a lot of things,” Lauro said, looking back. “We didn’t have a lot of time together, but I am amazed at how much we accomplished. Initiatives that we tried to push took years and years to get through there, but some things, we did get through. This is going to sound immodest, but I do believe that during my term as Secretary of Education, we made some of the most significant gains of any of the other administrations.”

Back in Training

After retiring from the Army in 1984, Dick – always a man of action – was not content to just sit home. The following year, President Reagan appointed him to the Chemical Warfare Review Committee, but the bulk of his time was focused on military training efforts.

While on active duty, Dick had bolstered training programs for soldiers, squads, platoons, companies, battalions and even brigades. Now, he focused on training opportunities for division and corps leaders – the commanders and staff. As the first senior mentor for the Battle Command Training Program, Dick taught the next generation of Army leadership how to lead through on-the-ground practice exercises, and the world saw the results in 1991’s Desert Shield and Desert Storm operations.

One of his protégés was Gen. Colin Powell, who would become the first African-American chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and, later, U.S. Secretary of State. In his autobiography, Powell called Dick an Army legend who saved his career.

As if serving his country wasn’t enough, Dick also served as a member of the Texas Tech Board of Regents from 1989 to 1995. Among the most important work done under his tenure was laying the groundwork for the Texas Tech University System that Lauro had advocated for. It was established in 1996.

Dick slowly withdrew from public life in his later years as he fought a lengthy battle with dementia, but he continued to be honored in many sectors. The Killeen Independent School District, near Fort Hood, opened the Richard E. Cavazos Elementary School in 2009. His hometown of Kingsville named Gen. Cavazos Boulevard in his honor. He was posthumously inducted into the Texas Tech Wall of Honor, a recognition of military alumni by the university’s Military & Veterans Programs.

On Oct. 29, 2017, the 50th anniversary of the start of his infamous battle at Lộc Ninh, Dick, 88, died, with Caroline at his side. The work he began, however, lives on. Fort Hood in 2019 dedicated the Gen. Richard Cavazos Mission Training Complex, which now supports soldiers through collective, simulation-driven command training. And in 2024, the entire base was renamed Fort Cavazos.

Educating the Future

After leaving Washington in 1990, Lauro didn’t give up on education. Instead of returning to TTUHSC to teach, he and Peggy returned to Massachusetts. With his national recognition, he became a public speaker on the importance of educational reforms. He also returned to the Tufts University School of Medicine, where he became a professor of family medicine and community health – a position he held well into his nineties.

In November 1993, he returned to Texas Tech for the dedication of his presidential plaques, one in the Administration Building breezeway that he’d reopened and one at TTUHSC, and to donate his many volumes of personal and professional files to the Southwest Collection/Special Collections Library.

“You can’t help but reflect on the past when you return to a building,” he said at the time. “But it shouldn’t be just looking back, it should be wondering about the future and where this institution is going.”

So it was oddly appropriate that on the very same day as Lauro’s plaque dedication, Lubbock Independent School District’s newly constructed middle school – just up the street from Texas Tech – was dedicated. Cavazos Middle School, a North Lubbock campus with a largely minority student body, was named in Lauro’s honor. During the dedication ceremony, Lauro made a personal promise to the students present:

“If, as you progress in your education, a thought comes to you and that thought is, ‘I’ve had it, I can’t go on with this education. I’m going to drop out,’ write to me,” he said. “I’ll write right back and convince you to stay in school.”

As his personal collection attests, people took him up on his promise. A first-year elementary education major at the University of Scranton wrote Lauro a four-sentence letter requesting his views on school vouchers to help her write a class assignment. His reply, dated only 10 days later, was one and a half pages long and contained his hope that it was not too late to be of help for her, as education was of the utmost importance to him.

After all, he attributed many of the Cavazos brothers’ successes to the education they received at Texas Tech. Looking back at the changes each of them implemented, he felt a great deal of pride.

“It’s incredible,” he recalled. “I’m pretty knowledgeable about educational institutions, and it’s beautiful and well done. It gives you the sense that this is a place where you can learn, and we did.”

Lauro died in March 2022. He was 95.

With the campus and academic environment Lauro helped bolster, the university system Dick helped create, and the student-athletes’ needs Bobby helped address, Texas Tech has truly been transformed by this one family.

“I hope my legacy,” Lauro said, “will be that I assisted in improving an institution that will educate many in the future.

“I love the place, I treasure the times I spent there and I really am grateful to the university for what it has given me and the whole Cavazos family. Think of all of the education it has imparted to all these young people!”

Think of all the great things they’ve done with that education.

Editor’s Note: Thank you to the Southwest Collection/Special Collections Library for access to the documents that allowed us to tell this story.