From 1984 to 2024, law students have built and defended the strongest advocacy program in the country.

Texas Tech University’s School of Law has built one of the nation’s most respected advocacy programs – and stands alone as the first in the nation to capture a national title in all five American Bar Association (ABA) competition categories: arbitration, negotiation, client counseling, mediation and appellate (moot court).

This rise to the top has nothing to do with luck and everything to do with hard work.

“The reason we consistently outperform other law schools is because we outwork other law schools,” said Director of the Advocacy Program and Champions in Advocacy Endowed Professor of Law Robert Sherwin.

Sherwin tells prospective students there is nothing inherently special about Texas Tech’s advocacy program. There is no magic pixie dust floating through the air vents.

A culture of excellence isn’t created overnight. It’s fostered and defended. But all traditions start somewhere. This one begins with a man named Don Hunt. Part of the early fabric of the law school, Hunt placed an emphasis on advocacy as he saw the world, and law, change during the 1970s.

Hunt built a legacy that’s now been honored for more than 40 years. And while everyone loves a win, these victories are merely evidence of a deeper conviction – the drive to make people’s lives better.

Mediation

“Believe it or not, but not every lawyer is as friendly as us,” jokes Caleb Kunde, a third-year law student at Texas Tech.

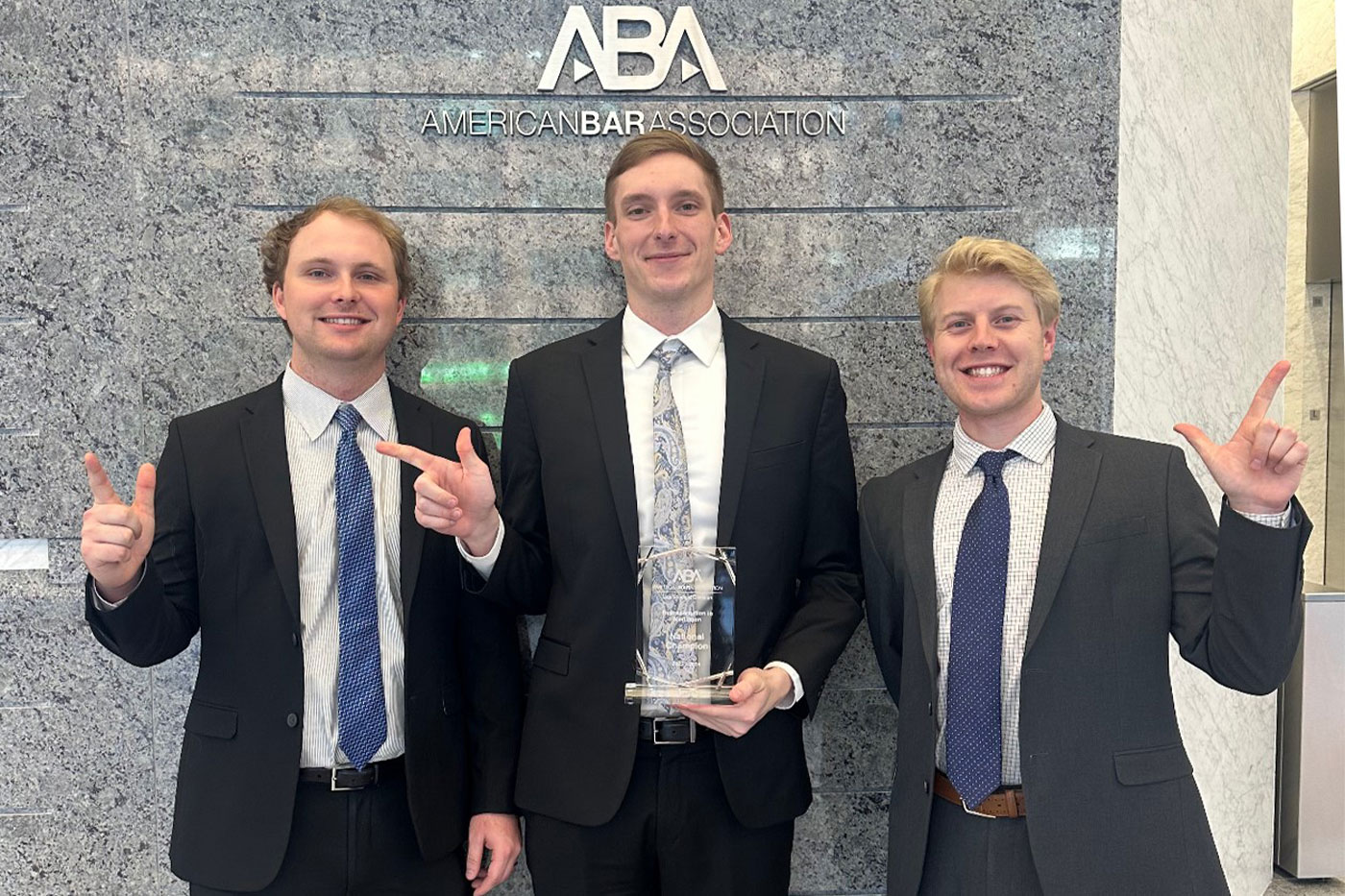

He sits with his friend Caden Jackson, another third-year student and recounts their win at the ABA mediation competition earlier this year.

“We had three weeks to prepare,” Kunde said.

The students got the case work for the competition two weeks ahead of time. After review, they flew to Denver for regionals. While Kunde and Jackson had experience in negotiation competitions, they’d never competed in mediation before.

They continued studying the case on the flight, drained the hotel business center of its printer paper and captured a win the next day. That victory propelled them to nationals.

Mediation was the most recent category added to the ABA competitions. Kunde and Jackson’s win in 2024 made Texas Tech’s School of Law the first to win in all five areas.

Kunde earned an undergraduate degree in meat science at Texas Tech’s Davis College of Agricultural Sciences & Natural Resources. He plans to use his law degree to represent mistreated workers in the meat industry.

“I worked in packing plants and saw that some folks, especially migrant workers, are taken advantage of,” he said.

Jackson plans to go into family law.

“Going through family court proceedings as a kid gave me a unique perspective,” he said. “As I got older, I knew I wanted to be in the role of helping kids going through those proceedings.”

Both aspirations will require an air-tight understanding of the law with an abundance of empathy, compassion and practical experience.

“These competitions help us become lawyers who will be with people on the hardest days of their lives,” Jackson said. “We have to be able to counsel people through those moments. That’s what makes Texas Tech’s program so unique. Everyone who graduates from here is a great practitioner.”

Building the Best

When Don Hunt moved to Lubbock in the ‘60s, he began work at Key, Carr, Carr and Clark.

“I cut my teeth there as a young lawyer,” he said in an interview in 1998.

Hunt’s trial experience quickly grew, particularly when the firm took on a case against Billie Sol Estes, one of the most notorious con men in Texas history. In the late 1950s, Estes created a $150 million empire by convincing countless Texan farmers to purchase ammonia tanks for fertilizer storage, sight unseen. The mortgages he produced were mostly bought on credit. In the 1960s, it became clear the tanks were nonexistent. But by that point, the mortgage holdings had been used to get loans from banks all over the country.

The case was taken on by the Federal Bureau of Investigation. Estes was tried and convicted on both state and federal charges and was sentenced to 24 years in prison.

While Hunt had no direct involvement with Estes, he helped represent many farmers who were victims of the scam. He oversaw gathering depositions.

“This would usually take a few hours on most cases,” Hunt said. “I took depositions for eight months.”

When Texas Tech opened its law school in 1967, the administration was searching for faculty members. Hunt was brought on as an adjunct professor in 1974. While he taught classes, Hunt volunteered a large amount of time to the trial and appellate advocacy teams by serving as the faculty advisor. It was under his leadership that the program became one of the best in the country.

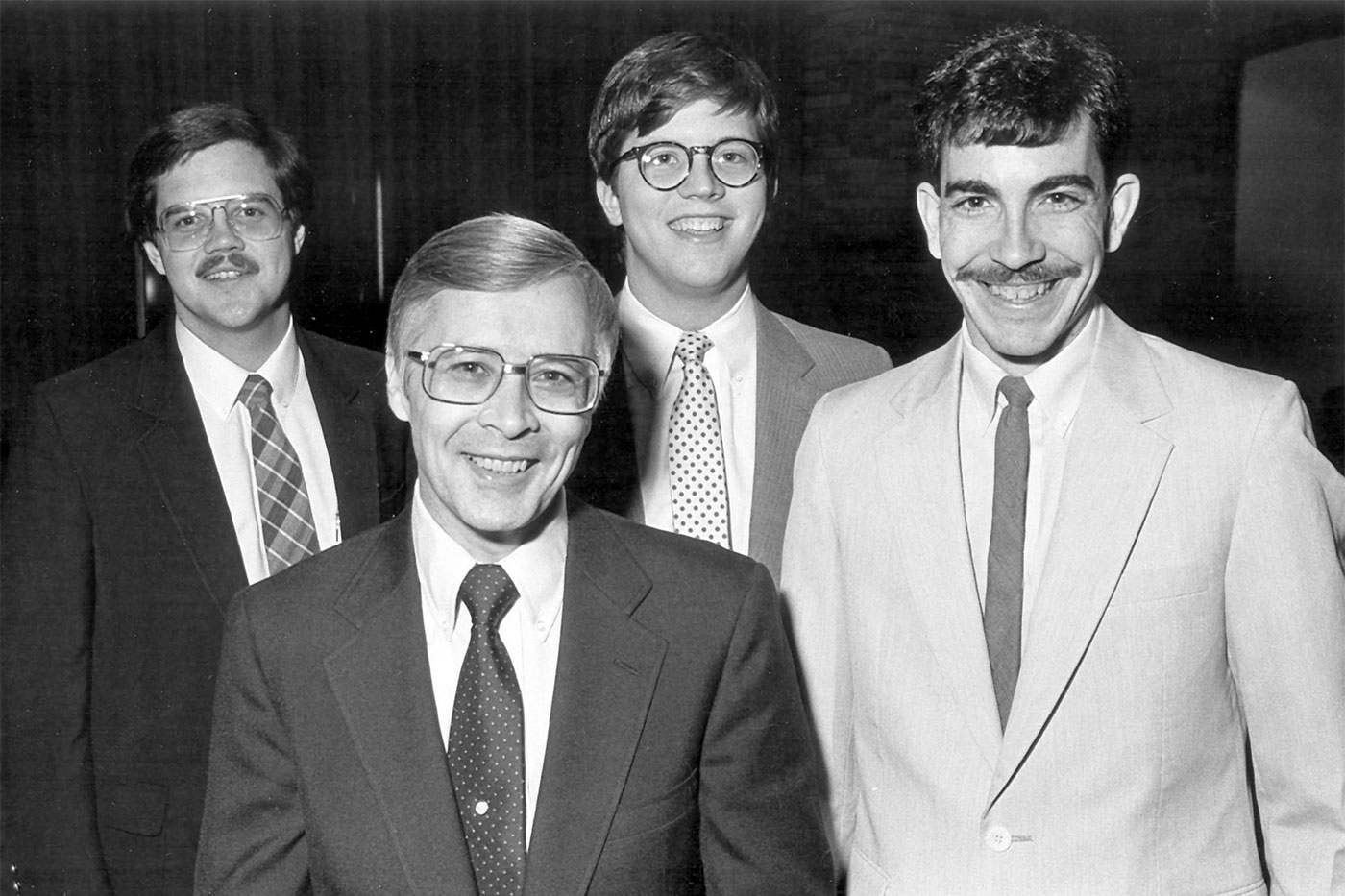

In 1984, Hunt coached a team to a national title in appellate advocacy. It was the Law School’s first national title in one of the ABA competitions.

One of the students on that team was Mark Lanier.

“Hunt was exacting,” Lanier said. “He had us work around the clock. He was a perfectionist. He’d even bring in judges to critique our arguments.”

Lanier remembers a few games of 42 and Risk during those days too, and that Hunt knew how to have fun when it was needed.

Lanier’s team won regionals and advanced to the national finals in Chicago. Much like a debate tournament, competitors do not know what side of the argument they’ll be representing, so they prepare for both.

“We were happy with the side we got,” Lanier remembered. “But we were curious whether we were going to get a hot bench.”

A hot bench refers to judges who’ll often interrupt with questions. Lanier says it’s hard to stay focused in this situation because you have to answer the questions and then effectively weave those answers back into your argument.

The bench was hot that day.

“That made it a whole lot of fun,” Lanier said, with a smile.

Lanier has gone on to become one of the best civil trial lawyers in the nation. He has gained justice for victims of dangerous drugs and medical devices, asbestos exposure and other harmful products.

Cumulatively, Lanier has won his clients close to $20 billion in verdicts.

In 2008, the Lanier family made a $6 million gift to the School of Law to build the Mark and Becky Lanier Professional Development Center. Most recently, in 2023, the Lanier family continued their support with an additional gift of $1 million to establish the Fred Gray Endowed Chair for Civil Rights and Constitutional Law. These gifts have significantly enhanced the education of every law student who comes to Texas Tech.

At the heart of the center lies the “Don Hunt Courtroom,” a space where the advocacy program cultivates champions, preparing them for competition with the same passion and determination as its namesake.

Fear & Humility

Jessica Whitacre Thorne is a managing member of Estes Thorne Ewing & Payne PLLC. She has had extensive success in family law and business litigation. It’s not what she envisioned when she went to law school but her time in the advocacy program revealed interests she didn’t know she had.

After a national win on Hunt’s appellate team in 1994, Thorne tried other teams, wanting to experience as much as she could. She remembers practicing with Hunt. He gave precise and tough critique, but it always inspired her to get up and try harder the next day, even when she lacked confidence.

“Texas Tech had a reputation for its advocacy program and there weren’t many opportunities to do advocacy at the time,” she said. “Back in the 90s, there were not a lot of law schools pushing it.”

To this day, Thorne believes in the power of oral advocacy. It’s vital in the work she does for families. She realized early in her career that she enjoyed family law. It allowed her face-to-face time with clients, and it was something she felt really mattered.

Thorne encourages the next generation of law students to lean into the experiences and opportunities that may feel uncomfortable. Things they’re not automatically good at.

“I think anything worth doing comes with a bit of fear and humility,” she said.

Priorities

Robert Sherwin was on his way to becoming a journalist when he took an undergraduate course at Texas Christian University on law and ethics of mass communication.

“I enjoyed that class and thought, ‘Maybe I want to use my journalism degree and go to law school,’” Sherwin recalled.

He applied to a few schools and was accepted to Texas Tech with a scholarship.

He decided to drive out and visit campus for a law school event. While he was there, he witnessed the final round of the first-year moot court competition.

“I immediately was in love with moot court and advocacy,” he said.

Sherwin didn’t know of other schools that would give him the practical court room and litigation experience he would gain through Texas Tech. When the first day of class started in the fall, he was there.

While Sherwin didn’t clinch any national championships, he was a member of two ABA NAAC regional championship teams and was a national semifinalist in multiple competitions. He returned to Texas Tech to become the director of the advocacy program in 2008 and has led nine teams to national wins.

He’s also worked with every coach who has come through the program.

Like Lanier and Thorne, Sherwin was trained by Hunt.

“Hunt was a giant in the advocacy community,” Sherwin said. “I still have coaches who come up to me and reminisce about meeting him or arguing against his teams.

When Sherwin was a student, he remembers Hunt laying down the law on the first day of practice.

“Hunt got up in front of us and said, ‘Your first priority is to your God and your beliefs. Your second priority is to your family. Your third priority is to your schoolwork. The rest of your time is mine.’”

Hunt set a precedent for hard work and rigorous training. So much so that the school does not allow first-year law students to compete on national teams. Sherwin says it’s important that first-year students focus on becoming good students before the demands of competition are added.

First-year students can practice during intra-school competitions through a student organization called the Board of Barristers. This allows them to apply what they’re learning without the pressure of competing on a regional or national level.

After Hunt retired, Sherwin leaned heavily on long-time advocacy coach Murray Hensley. Hunt brought Hensley on in 1984 to help coach arbitration teams while he focused on the appellate teams. The divide and conquer technique worked well.

Arbitration is similar to a traditional courtroom trial but includes three arbitrators (judges) and no jury. It’s used to avoid the long, drawn-out process of going to court. It’s also a more economical avenue.

Hensley was skilled at preparing students for arbitration.

Arbitration

Judge Michael Davis presides over the 396th Judicial District in East Texas. He was on the first Texas Tech team to win a national title in arbitration in 2008.

“When I graduated high school, I did not have the resources to go straight to college,” Davis said. “So, I served six years in the U.S. Air Force.”

Wanting to see the world, he was sent to the lively city of Grand Forks, North Dakota.

“Luckily, Uncle Sam made it up to me because my second assignment was to the Aviano Air Base in Italy,” Davis said.

When he finished his time in the military, he went to Texas State University—San Marcos to study psychology and philosophy. He’d known for a long time he wanted to go to law school, and after a decade, Texas Tech gave him that opportunity.

“Texas Tech offered me a scholarship and when I came out to visit the campus, I knew this was the place for me,” he said. “I instantly committed.”

Davis said the advocacy program was phenomenal, and one of the main reasons he’s been so successful in his career.

Davis was coached by Hensley and Shery Kime-Goodwin.

“I cannot say enough good things about them both,” he said.

Hensley and Kime-Goodwin also worked elsewhere in Lubbock but would come to campus multiple nights each week and a good chunk of the weekends to spend time coaching the team.

“They donated their personal time to mentor us,” Davis said. “Their personal sacrifice to help us improve our advocacy skills meant a lot.”

That sacrifice made students willing to work hard; knowing the coaches wanted to be there was extra incentive to bring everything they had.

Davis likened practice to training for a marathon. He remembers working long into the evenings revising and running through arguments until they were razor sharp. He could recite his opening and closing arguments from memory.

“There is a commitment to excellence,” he said. “When Texas Tech shows up to these competitions, we’re there to place first. We’re not after a participation trophy.”

Davis pulls daily from the lessons he learned at Texas Tech. As a judge presiding over a general trial jurisdiction, he handles a variety of cases, from business disputes to murder trials and everything in between. Davis became a judge at age 40, a milestone that usually comes later in one’s career.

“The education I received at Texas Tech taught me how to tackle cases and helped me excel as a practicing attorney,” he said. “This helped me develop a great reputation in my legal community which ultimately led me to the bench.”

Davis flies into Lubbock weekly to teach as an adjunct professor. He often walks down a hall named after his late mentor. A plaque with a picture of Hensley hangs in that hall. It reads:

“Famous for his quick wit and jovial personality, Murray ‘never met a stranger’ and was revered by fellow mock trial coaches across the nation.”

After beating brain cancer in 2000, Hensley’s cancer returned. He passed away in 2011.

Unmatched

“Murray was the heart and soul of our program,” Sherwin said.

Sherwin took on a more active role coaching teams after Hensley’s death, along with Professors Kline-Goodwin, Dick Baker and Cassie Christopher. They’ve coached many students to victory over the past decade. One of those students was Laney Piercy.

Piercy is now a partner at Glasheen, Valles & Inderman, LLP, where she practices as a personal injury attorney. After earning her undergraduate degree at University of California, Berkeley, Piercy wanted to attend law school in Texas to be closer to family.

“Texas Tech had one of the highest bar passage rates in the state,” she said. “It was also affordable. Other law schools would cost more in tuition and didn’t always offer the real world practice opportunities that Texas Tech’s advocacy team offered.”

For her, it was a simple choice.

Piercy became heavily involved in interschool competitions and the national competitions, too. She was on an arbitration team that won a national title in 2014. She remembers the practice being grueling, but perfect preparation for the real world.

“As a lawyer, I want to give my all to my client,” she said. “I can’t ever promise a win, but I can work quickly and find out what happened and why.”

For victims of personal injury cases, that’s often the closure that’s needed most.

The summer before her third year of law school, Piercy got a clerkship at Glasheen, Valles & Inderman. She didn’t know much about personal injury law at the time, but she’ll never forget the first case she worked.

On her first day, Chad Inderman, a senior partner at the firm and a Texas Tech Law alumnus, came to her office and offered her the chance to travel to Amarillo with the team. They’d be taking depositions for a new case.

“A 22-year-old man had fallen down an elevator shaft and died,” Piercy recalled. “I was 22 at the time, and that case hit close to home.”

The elevator’s platform had been removed and the owner of the building hadn’t taken the precautionary measures to mark it out of use. By the end of the summer, Inderman sent Piercy out solo to get recorded witness statements of the parents to use in a mock trial on the case.

“Most clerks don’t get the opportunity to interact with clients like that,” she said.

Piercy attributes the countless hours of practice in the advocacy program with being trusted with big cases so early in her career. Now, not even 10 years out of law school, she’s made partner.

Andrea Nfodjo is another graduate who won an arbitration national title. She now serves as the head mock trial coach and is an adjunct professor at the School of Law.

Nfodjo knew she wanted to be in a profession that helped people, and, with a degree in criminal justice from the University of Texas at Arlington, she turned her sights to law.

When it came time for law school, she looked at Texas Tech.

“The program is unmatched,” she said. “The coaches you have access to and the hours you can get in practical experience are unique.”

Nfodjo enjoyed the national win she secured with her team in 2017, beating out Drake University School of Law in the final round.

“I don’t know if people always see Texas Tech coming,” she said with a grin.

Nfodjo is now a prosecutor for the Dallas County District Attorney’s Office. She handles a lot of criminal cases, balancing what’s in the best interest of the victim and the community, while ensuring fairness to the person accused.

In her first month on the job, she had to handle a motion to suppress.

“I had the skills to get that done because of the training I got at Texas Tech,” she said. “Graduates come out ready to try cases.”

While that statement may seem like a given for any law school graduate, it’s not always the case. According to faculty at Texas Tech’s School of Law, many private and Ivy League law schools focus more heavily on theory. This is a valuable endeavor and can prepare future lawyers for niche career paths, such as the Supreme Court.

Problems arise when an alumnus comes out of a theory-based school wanting to practice trial law. They often lack the experience to do so. For many law students, a more practical program and curriculum is helpful.

However, on the whole, lawyers are spending less and less time in courtrooms.

In 2024, The National Center for State Courts collected data that shows caseloads down by 18.7 million compared to 2019. While COVID-19 accounts for some of this, experts wonder if the number of cases that see the inside of a courtroom will ever return to pre-pandemic levels.

“Now more than ever, the law needs lawyers who are willing to get into the courtroom and try cases because the art of trial advocacy is dying,” Sherwin said.

He says not many cases get tried anymore due partially to cost and partially because of the risk for the litigating parties. As a result, lawyers don’t get as much practice trying cases as they once did, even in appeals. More recently, courts of appeals tend to ask for written briefs rather than oral arguments.

“Now, one might say, ‘Well, then why does any of this matter? If we're doing less of it, why do we need to train people to do it?’” Sherwin said. “My response is exactly the opposite. Yes, we’re doing less of it, but that means when we do it, the person doing it needs to be experienced, because it has that much more added importance.”

Sherwin says Piercy’s firm recently won a $262 million judgment in Ector County because it was willing to try a case against a defendant that thought they’d back down.

Many wealthy and powerful corporations can make these assumptions – that the other side will back out or merely not have the money to take them to court.

“That makes a good lawyer go, ‘You know what? I’m not going to let you get away with that. I’m going to put you in the courtroom, and we’re going to find out what the truth is,” Sherwin said.

Bettering People’s Lives

Mark Lanier almost wasn’t on the appellate team in 1984. In fact, he almost didn’t attend law school at all. Earning a bachelor’s degree in biblical languages, he planned to become a minister. But he felt led to law at the same time.

“I figured if I went the law route, I could do both,” he said. “I still preach; I just don’t take a paycheck for it,” he said.

This has enabled him to fund his interests in theological study and helping his neighbor. On a recent trip back to campus, he sat at a large conference table drinking a bottle of water after speaking to a group of law students. There was a steady smile that never left his face.

When he reminisced about being on the very first team from Texas Tech to win a national ABA competition, he beamed with pride.

“It’s a cool thing, you know, to leave your fingerprint on something other than a crime scene,” he said.

Lanier’s journey continues to inspire. Like him, the students who follow in his footsteps are driven by a desire to make a difference. And that’s what the advocacy program at Texas Tech makes possible.

Each new generation of students carries forward the legacy of excellence and dedication set in motion by early leaders like Don Hunt and Murray Hensley. Guided by exceptional coaches and professors, students like Caleb Kunde and Caden Jackson embody a commitment to rigorous preparation that extends far beyond competitions.

Today, the impact of Texas Tech’s advocacy program ripples out into the world, carried by alumni like Lanier, Davis, Nfodjo, Piercy and Whitacre Thorne. These dedicated professionals continue the tradition of advocacy, standing up for those who need it most – whether it’s individuals, families or entire communities.

“At Texas Tech School of Law, we love to celebrate our wins, but winning is never the end goal,” said Jack Wade Nowlin, dean of the School of Law. “Each success reflects our dedication to something much larger – the relentless drive to change lives, one argument, one case, and one client at a time. That’s what makes this program so special.”

This story is dedicated to all the students who have created a tradition of excellence within the advocacy program, and to Donald M. Hunt and D. Murray Hensley.

Texas Tech’s School of Law ABA National Championship Teams:

National Appellate Advocacy Competition:

’84—W. Mark Lanier, James R. Dennis and Jeffrey S. Alley

’94—Jessica L. Whitacre (best oralist), Michael S. Truesdale (best brief) and Mai Lan Isler

’98—Shelley A. Hallman, R. Scott Mayo and Michael Murray

’13—Reagan Marble, Ashirvad Parikh and Suzann Taylor

’21—Taylor Holley, Alicia Mpande and Jay Evans

Arbitration:

’08—Jesse Blakley, Tiffany McDuff, Joe Putnam and Mike Davis

’10— Sam Ackels, Matt Butler, Paul Miller and Courtney Stamper

’12— Wade Iverson, Meredith M. Mills, Jared Mullowney and Kate Murphy

’14—Laney Piercy, Caleb Miller, Taylor Stoehner and Drew Thomas

’17—Ryley Bennett, Brian Burkhardt, Brent Debnam and Andrea Nfodjo

’20—Patricia Cabrera-Sopo, Emily Fouts, Michael Samaniego and Drake Pamilton

Negotiation:

’92—R. Lane Brindley and Joseph E. Byrne

’97—Cynthia L. Wilkinson and Michael A. Yanof

’19—Taylor Calvert (International)

Client Counseling:

’87—Kevin T. Glasheen, Jody L. Hagemann and Brian Loncar (International)

Mediation:

’24— Caden Jackson and Caleb Kunde